The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is deeply personal to me. I am Israeli, and still have family in Israel. I also have Palestinian friends and acquaintances. Death and suffering are not abstract or theoretical notions. They will always affect someone that I know. As such, it can be a painful topic for me to discuss, but I do want to raise some perspectives that I feel are missing from the popular debates on blogs and social media now that violence has escalated in the Gaza Strip. Needless to say, my views are my own. Difficult Run has multiple voices, and welcomes different views. Before I proceed, I would like to direct the reader to two even-handed and reasonable pieces written by people that I know personally. While I disagree with both to some extent (the Mercurio quote can get tiresome), I appreciate the way that they frame their views, and recommend reading them. It is worth the time.

In this post I want to look at a major aspect of Hamas, the terrorist organization that became the ruling party in Gaza. Recently there have been several voices arguing that Hamas has been “horrendously misrepresented.” Most recently, Cata Charrett claimed that Hamas should be seen as a “pragmatic and flexible political actor.” This is essentially the same argument made earlier by others like Jeroen Gunning who produced pioneering research on the political side of Hamas.[ref]Gunning’s important study, Hamas in Politics, should be read cum grano salis due to an apologetic stance which spoils many of his insights. For example, Gunning considers that Hamas has “broadly followed” the ceasefire because although it fired rockets, it did not send suicide bombers.[/ref]

Hamas’ position, though, is not merely political, but draws deeply from certain metaphysical assumptions which frame their struggle. I’ll grant that divergent opinions certainly exist amongst the Hamas leadership. Some are pragmatists, and many others are decidedly hardliners. However, they do share a certain world-view.

Hamas’ founder, chief ideologue, and spiritual leader, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, considered Palestine a waqf, that is, something consecrated to God. He formulated this belief as article 11 of Hamas’ Covenant, its charter document.

“The Islamic Resistance Movement believes that the land of Palestine is an Islamic waqf consecrated for future Muslim generations until Judgment Day. It, or any part of it, should not be squandered: it, or any part of it, should not be given up. Neither a single Arab country nor all Arab countries, neither any king or president, nor all the kings and presidents, neither any organization nor all of them, be they Palestinian or Arab, possess the right to do that. Palestine is an Islamic waqf land consecrated for Muslim generations until Judgment Day… This is the law governing the land of Palestine in the Islamic Sharia…”

Treating the land that way means that any permanent concessions can be construed as blasphemy against God himself and Islam (which of course aren’t considered completely separate concepts). There is also no earthly authority that can do so because it cannot speak for all Muslim generations. Compromise can only be tactical, and thus, limited. It makes negotiating with Hamas to achieve a peaceful state of coexistence a decidedly tricky prospect. As the concept is part of their founding covenant, it cannot simply be laid aside, even when they somewhat moderate their stance, or express some discomfort with the wording.[ref]The main discomfort has been more with the phrases used than the ideas behind them. This article discusses a Hamas initiative to change the Covenant’s wording, but eight years have passed with no change.[/ref] For example, much has been made of Hamas dropping the call to destroy Israel from its 2006 election manifesto. However, the evidence suggests that this was downplaying a fundamental position in order to focus on domestic political ambitions. The fundamental position itself did not change. This is despite Charrett’s insistence that the 1988 covenant is irrelevant to understanding the contemporary Hamas. Ghazi Hammad, a Hamas politician, said in 2006, that “Hamas is talking about the end of the occupation as the basis for a state, but at the same time Hamas is still not ready to recognise the right of Israel to exist… We cannot give up the right of the armed struggle because our territory is occupied in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. That is the territory we are fighting to liberate.”

Hamas has sought not a lasting peace, but a hudna, a temporary, multi-year cessation of violence for which it demands a very high price. Yes, Hamas has offered to recognize the June 1967 borders, but only for 10-20 years, and conditioned on Israel granting Palestinians the right of return and evacuating all settlements outside of said borders. Those terms should be worked out, but as part of a lasting, normative peace. When the twenty years are up (or less), Israel will find itself disadvantaged, its very existence considered an act of aggression. Khalid Mish’al, Hamas’ current leader, wrote in 2006 that, “We shall never recognise the right of any power to rob us of our land and deny us our national rights. We shall never recognise the legitimacy of a Zionist state created on our soil in order to atone for somebody else’s sins or solve somebody else’s problem.” In order to obtain another hudna, Israel will have to make concessions just as big. The possibility of permanent peace is vaguely left to the judgment of the next generation.[ref]While the conclusions of this paper are debatable, the quotes presented are very useful.[/ref]

Now, there are Jewish metaphysics of the land, too. The most famous is it being the land promised by God to his people Israel. Rabbi Yaakov Moshe Charlap, a prominent member of Rabbi Kook’s circle in the first half of the 20th century, considered the land of Israel a part of the highest aspect of the Divine. ‘‘In days to come, [the land of] Israel shall be revealed in its aspect of Infinity [Ein Sof], and shall soar higher and higher… Although this refers to the future, even now, in spiritual terms, it is expanding infinitely.’’ Charlap further considered Jewish settlement of the land of Israel as an essential condition for holiness to spread throughout the world. His teachings were very influential amongst radical Jewish settlers in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. More recently, R. Yitzchak Ginsburg taught that Chabad’s seventh rebbe was the manifestation of the Divine, and that in order to return him to this world the land of Israel must be saved from “Arab hands.”[ref]Jonathan Garb, The Chosen will become Herds: Studies in Twentieth Century Kabbalah (Yale University Press, 2009), 62, 67-68.[/ref]

The major difference that I see is that Israel-even under a right-wing government- has shown itself willing to act against groups with such metaphysical views. When unilaterally disengaging from the Gaza Strip in 2005, the Israeli government dismantled the Jewish settlements, and expelled the settlers. The settler ideology (particularly in the Gaza Strip), as I’ve mentioned, was highly informed by teachings like that of Charlap’s. Such metaphysics, though, do not form an integral aspect of Israeli policy. Israel may be right or wrong about many things like the Gaza disengagement, but that is beside the point. Although I love it dearly, it is certainly an imperfect state. What matters here is the ability to lay aside metaphysics of the land and carry out concessions that are unpopular with many of its constituents.

Perhaps Hamas will change into a truly moderate force. Perhaps.

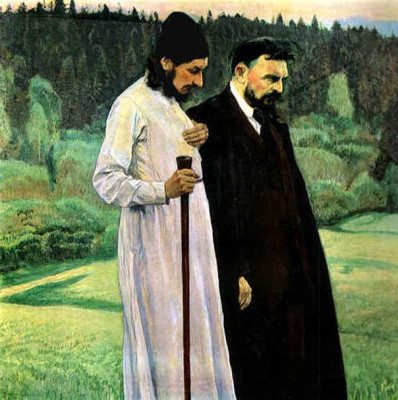

Florensky grew up in the Caucasus. He claimed that his childhood there lent him “an objective, noncentripetal perception of the world, a kind of inverse perspective” which allowed for a “penetration into the depth of things.” The Caucasus is a wild and mysterious region with snow-capped mountains, deep ravines, and roaring rivers. It exerted a tremendous influence on Russian writers, and although I had read extensively on it, nothing prepared me for my first glimpse of it. Pictures can never convey just how remarkable it is. I then understood instinctively Tolstoy’s laconic cry, “the mountains, the mountains,” and I confess to being a little awestruck even today.[ref]Some of my favorite books on this topic are Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat, Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Times, and Lesley Blanch’s The Sabres of Paradise: Conquest and Vengeance in the Caucasus. These give an idea of the pull that the Caucasus can have on the imagination.[/ref] I share this because there really is a feeling there of a “native, solitary, mysterious and infinite Eternity, from which everything flows and to which everything returns,” as Florensky described it. Paradoxically, it was this other-wordly feeling that Florensky claimed enabled one to see the world as it really is. “The child has absolutely precise metaphysical formulas for everything other-worldly, and the sharper his sense of Edenic life, the more defined is his knowledge of these formulas.” It is hard to imagine someone like Wallace Stegner concurring with Florensky’s definition of objectivity, yet as Nathaniel noted, the scientific narrative has increasingly tended to absorb and adapt religious ones, resulting in something not far removed from Florensky’s objectivity.[ref]See the multiple examples in Carl Youngblood’s recent MTA

Florensky grew up in the Caucasus. He claimed that his childhood there lent him “an objective, noncentripetal perception of the world, a kind of inverse perspective” which allowed for a “penetration into the depth of things.” The Caucasus is a wild and mysterious region with snow-capped mountains, deep ravines, and roaring rivers. It exerted a tremendous influence on Russian writers, and although I had read extensively on it, nothing prepared me for my first glimpse of it. Pictures can never convey just how remarkable it is. I then understood instinctively Tolstoy’s laconic cry, “the mountains, the mountains,” and I confess to being a little awestruck even today.[ref]Some of my favorite books on this topic are Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat, Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Times, and Lesley Blanch’s The Sabres of Paradise: Conquest and Vengeance in the Caucasus. These give an idea of the pull that the Caucasus can have on the imagination.[/ref] I share this because there really is a feeling there of a “native, solitary, mysterious and infinite Eternity, from which everything flows and to which everything returns,” as Florensky described it. Paradoxically, it was this other-wordly feeling that Florensky claimed enabled one to see the world as it really is. “The child has absolutely precise metaphysical formulas for everything other-worldly, and the sharper his sense of Edenic life, the more defined is his knowledge of these formulas.” It is hard to imagine someone like Wallace Stegner concurring with Florensky’s definition of objectivity, yet as Nathaniel noted, the scientific narrative has increasingly tended to absorb and adapt religious ones, resulting in something not far removed from Florensky’s objectivity.[ref]See the multiple examples in Carl Youngblood’s recent MTA