This post is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

We’re gonna start in a little bit of a strange place today, with an obscure (to most people) science fiction writer named Olaf Stapledon who lived from 1886 to 1950. One of Stapledon’s important works [ref]Important for the history of science fiction, anyway, and relevant to today’s General Conference musings, too.[/ref] is a book called Star Maker. According to Wikipedia:

We’re gonna start in a little bit of a strange place today, with an obscure (to most people) science fiction writer named Olaf Stapledon who lived from 1886 to 1950. One of Stapledon’s important works [ref]Important for the history of science fiction, anyway, and relevant to today’s General Conference musings, too.[/ref] is a book called Star Maker. According to Wikipedia:

The book describes a history of life in the universe, dwarfing in scale Stapledon’s previous book, Last and First Men (1930), a history of the human species over two billion years.

So, Last and First Men covered the history of the entire human species and spanned two billion years. And it was dwarfed by Star Maker.

This brings us to one of the perennial problems of science fiction. It was a problem for Olaf Stapledon writing before World War II, it was a problem for writers like Isaac Asimov grappling with his galaxy-spanning Foundation epic in the 1980s, and it’s still a tough one for contemporary stories like the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy by Chinese sci-fi author Liu Cixin, released in China from 2008-2010 and in the US from 2014-2016.

In his series of lectures, How Great Science Fiction Works, Gary K. Wolfe named the problem after Stapledon and described the problem this way:

…for all these mind-blowing vistas of deep space and deep time Stapledon invites us to ponder, how do you make a human-scaled story out of this with fully drawn characters and emotional reactions that a reader can relate to in some sort of traditional novelistic fashion?[ref]My own transcription of one of his lectures from The Great Courses[/ref]

Now, here’s the thing: this is not just a problem for science fiction.

Human beings live and breathe stories and narratives. Narratives, fundamentally, are the way we understand the universe around us. When we come to the biggest and most important questions of all—things like, What is the meaning of life? or What is truly good?—we frame our answers in terms of stories. The Gospel, what we call the Plan of Salvation, is delivered in terms of a story. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end. It has heroes and villains. It has a climax and a resolution. And it also has a really, really large scope.

So if we want to understand the gospel narrative—if we want to grasp the Plan of Salvation—then we actually end up confronting the Stapledon Problem in our own scriptures.

If that sounds far-fetched or like a bit of a stretch, let me give you this concrete example. Have you ever heard an atheist mock religion using an argument that goes a little like this: “So,” our hypothetical atheist says, “You’re telling me that you believe the God who created the Earth, the Solar System, the Milky Way, and the entire Universe—containing billions more galaxies each with billions of planetary systems of their own—that God actually cares whether or not you say your prayers tonight?” This is the Stapledon Problem.

So let’s keep that in mind as we think about Elder Eldred G. Smith’s talk from the Sunday afternoon session of the April 1976 General Conference. Elder Smith cites President J. Reuben Clark:

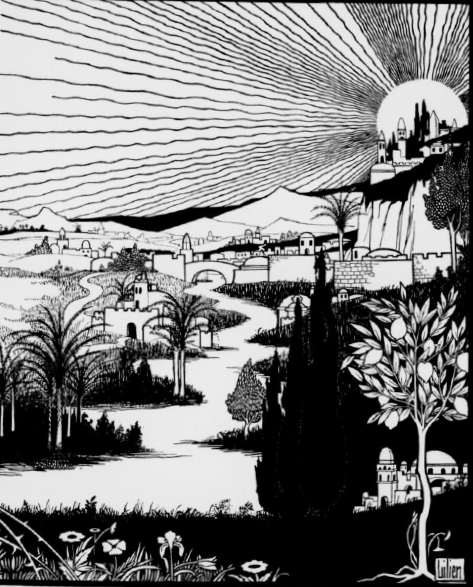

And if you think of this galaxy of ours having within it from the beginning perhaps until now, one million worlds, and multiply that by the number of millions of galaxies, one hundred million galaxies, that surround us, you will then get some view of who this Man we worship is.

The Stapledon Problem in Mormonism is that we’re not really quite sure how to picture God in general and Christ in specific. On the one extreme, we have the Lorenzo Snow couplet:

As man now is, God once was:

As God now is, man may be.

The couplet itself has not been canonized, but the sentiment behind it is basically doctrinal.[ref]Reference for that would be the 1982 Ensign, in which Gerald N. Lund opens his discussion with, “To my knowledge there has been no “official” pronouncement by the First Presidency declaring that President Snow’s couplet is to be accepted as doctrine. But that is not a valid criteria for determining whether or not it is doctrine.” He ultimately concludes: “It is clear that the teaching of President Lorenzo Snow is both acceptable and accepted doctrine in the Church today.” The Ensign isn’t canon and so it can’t establish canon, but at a minimum this is a clear indication that the couplet is pretty deeply embedded in Mormon belief.[/ref]

This view of God is pretty radical, and it seems to envision God as basically a super-advanced sentient being, which is (ironically) the kind of God that even someone like notorious atheist Richard Dawkins could theoretically envision. He has said, for example:

Maybe somewhere in some other galaxy there is a super-intelligence so colossal that from our point of view it would be a god. But it cannot have been the sort of God that we need to explain the origin of the universe, because it cannot have been there that early.[ref]From an interview with Sheena McDonald in 1995, via Wikiquote[/ref]

This kind of God—the one that seems to be implied by President Snow and that even Dawkins would grudgingly concede is theoretically plausible—is radically different from the God of historical Christianity, which Hugh Nibley has derisively referred to as “the God of philosophers.” That kind of God—the one “we need to explain the origin of the universe” would have to be the “unmoved mover” (to plunder Aristotle).

The trouble is, we believe in that kind of God, too. In the very same session, Elder L. Tom Perry spoke eloquently about this kind of God. Not one who perfectly follows the laws of nature, but a God who decides the laws of nature. Thus, after describing how God tilted the earth and started it spinning, Elder Perry mentions, “His physical laws,” which “are eternal and unchangeable.” He also emphasizes, “As man grows in his understanding of God’s physical laws, he can know with absolute assurance what the result will be if he conforms to those laws.”[ref]Emphasis added in both quotes.[/ref]

I am not trying to tell you that Elder Perry and President Snow contradicted each other. That is going too far. It is certainly possible to reconcile their statements. There are many views that could embrace both perspectives. But I am telling you that there is a tension between those two views, and that that tension pervades the way Mormons talk and think about God. Depending on who you talk to—and sometimes depending on when a person is talking—we emphasize either the facets of God that are most like us (for example, His ability to weep and be deeply impacted by the decisions of His children) are the facets of God that are most majestic and awe-inspiring and therefore least like us (such as his ability to set down the physical laws which govern the universe).

And this tension is the Stapledon Problem.

For science fiction authors, the question is: how do incorporate aeons and lightyears into stories that still have a meaningful place of human beings? How do you make such stories fun and accessible and comprehensible? Science fiction authors are, in the end, trying to entertain us.

The Gospel is obviously not a question of entertainment, but—because we understand it as a narrative—it faces the same problems of cohesion and coherence in the face of vastly disproportionate scopes. How do we reconcile a God who ignited the suns and breathed life into the first humans with praying to that God to find our lost keys? Or thinking that God cares about anything we pray about?

Since I’ve raised the issue, let me hazard a few words in closing. First, I do think it’s a bit silly to criticize people for praying to find their lost car keys. This has become a little fashionable as late, and you can find memes making fun of athletes who pray in thanks in the end zone. And, well, OK. That does seem a little ridiculous to me. Anyone who prays to God that their team will win a game is uttering the kind of prayer I simply cannot understand. But that’s because I don’t understand fanatical sports loyalty at all. But let’s set aside issues of weirdly sublimated ritualistic tribal warfare for another day. The point I’m driving at is that if we’re talking about the author of the universe, then the difference between praying for your car keys and—not to be too blunt about it—praying for your life seem like a rounding error. If the being who created a billion galaxies listens to individual prayers at all, then whether those prayers are for life or death or for car keys probably doesn’t really matter. I mean, a billion galaxies compared to your life and a billion galaxies compared to your car keys, aren’t they both about equally absurd? It’s like scoffing at the notion of Bill Gates stopping to pick up a penny but taking it for granted that obviously he’d stop to pick up a nickel.

Second, the Stapledon Problem is an expression of our limitations. It says we can’t picture a really epic scope—galaxies and eons—and keep our focus on the significance of an individual human being at the same time. That’s beyond our capacity to do, which is why science fiction writers have to come up with all kinds of clever ways to get around it,[ref]This usually involves putting their characters to sleep for a century or so every now and then and/or playing with relativity effects so that all the key players can be awake and present for the important events taking places across centuries of time and hundreds of light-years.[/ref] but nobody said it was beyond God’s ability.

After all, his thoughts are not our thoughts. He framed the sky above the earth, and He still cares when a sparrow falls from the latter to the former. We don’t know how He does it. But we can still believe, affirm, and even know that He does.

—

Check out the other posts from the General Conference Odyssey this week and join our Facebook group to follow along!

- Families: Relationships Beyond This World by Jan Tolman

- To know Him by Marilyn Nielson