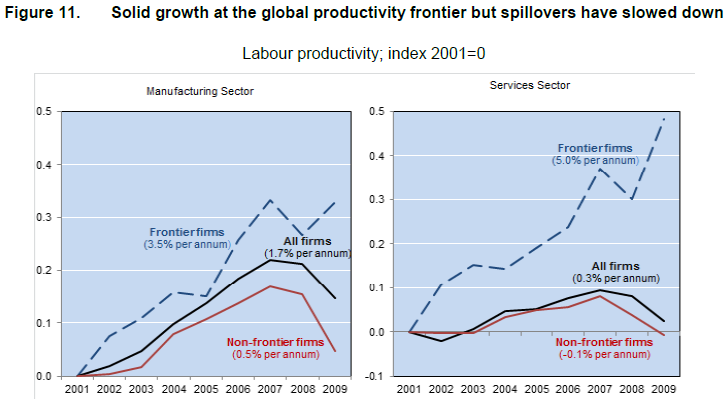

According to Noah Smith, a 2015 OECD report “looked at productivity not at the global or national level, but at the corporate level. Different companies have different technologies, different management systems and different levels of talent…At a small number of companies, productivity growth hasn’t slowed at all. If you look at only these “global frontier” companies, there has been no productivity slowdown at all! This is especially true in services industries…The top performers have blazed ahead, while other companies have stagnated or even become less productive.”

Smith offers a number of possibilities for this difference, but the most interesting one revolves around patents:

[I]ntellectual property law is making it harder for companies to use ideas developed at other companies. There has been an explosion in the number of patents granted in the U.S. since the early 1980s. In Japan the increase has been even more dramatic. Some of the fastest growth has been in patents for business methods — exactly the kind of thing that ought to diffuse across companies and equalize productivity. In earlier ages, businesses could freely copy each other’s way of doing things; now, it is often illegal.

Some level of patent protection, of course, is necessary to encourage innovation. But many economists believe that we now give out far too many patents, often for innovations of questionable originality.[ref]Economist Alex Tabarrok has criticized the mismatch between patent law and patent theory.[/ref] This is something we would expect to increase the gap between the most productive companies and the rest.

Whatever the reason for the divergence between companies, we need to find it and fix it if we can. The divergence could be affecting a lot more than productivity. A torrent of research in the past decade suggests that much of the increase in wage inequality in developed countries is due to differences in wages between different companies — work for a good company and you get better pay, work for a bad one and you’re out of luck. Fixing the productivity divergence might help us fight inequality as well.

Interesting stuff.