This is part of the Stuff I Say at School series.

The Assignment

After listening to [Benjamin] Ginsberg‘s lecture, do you agree with his assessment that politics is all about interests and power?

The Stuff I Said

Kevin Simler and Robin Hanson’s recent book The Elephant in the Brain demonstrates that these underlying desires for power and status inform many of our decisions and behaviors in everyday life. Politicians certainly do not transcend these selfish motives by virtue of their office. I would actually add a subcategory to “status”: moral grandstanding. We want to paint ourselves as “good people” by signaling to others our superior moral quality. This allows us to enjoy the social capital that comes along with the improved reputation. We not only gain status, but we can also think of ourselves as do-gooders; crusaders who fight the good fight. Unsurprisingly, evidence suggests that we have inflated views of our own moral character and that acts of moral outrage are largely self-serving. What’s unfortunate is that social media may be exacerbating moral outrage by making signaling both easier and less costly to the individual.

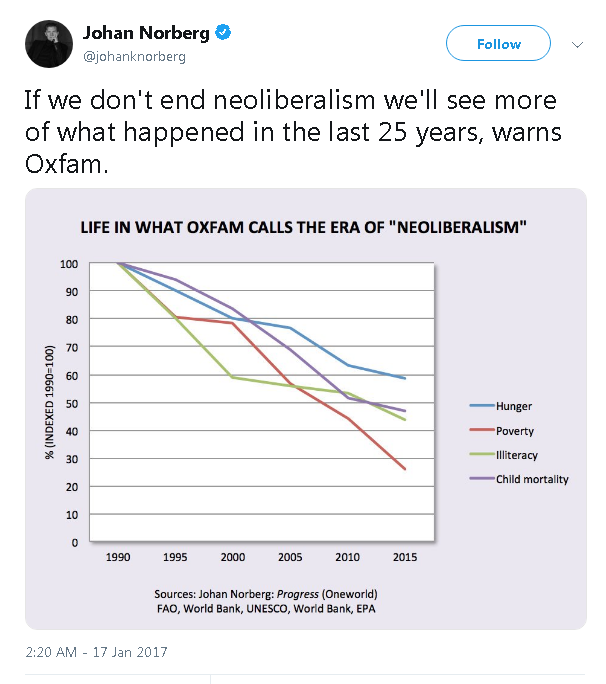

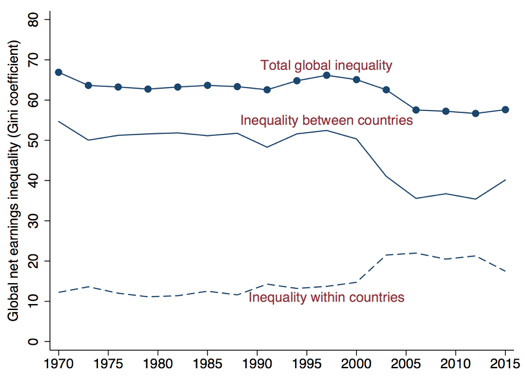

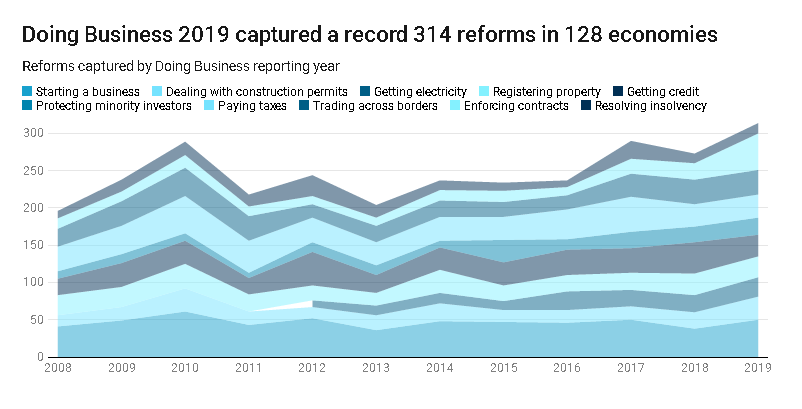

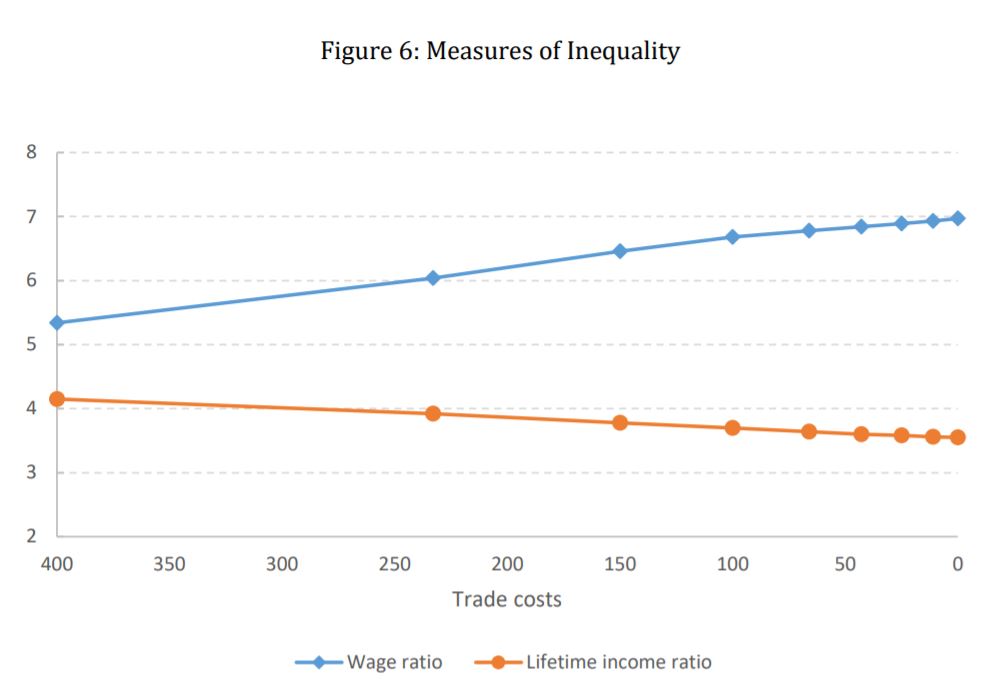

I think the rise of populism in both America and Europe is a timely example of interests at play. While various elements contribute to the populist mindset, economic insecurity is the water it swims in. And this insecurity has been exploited by politicians of more extreme ideologies across multiple countries. For example, the Great Recession eroded European trust in mainstream political parties: a one percentage point increase in unemployment was associated with a 2 to 4 percentage point increase in the populist vote. A 2016 study looked at the political results of financial crises in Europe from 1870 to 2014 and found that far-right parties were the typical outcome. In America, President Trump made “Make America Great Again” his rallying cry, feeding off the public’s distrust of “the Establishment” during the post-crisis years. In doing so, he advocated protectionism and tighter borders. Oddly enough, you find comparable populist sentiments on the Left: Bernie Sanders has been very anti-trade and iffy on liberalized immigration (open borders is “a Koch Brothers proposal“), all in the name of helping the American worker. One of his former campaign organizers–the newly-elected Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez–has also expressed similar concerns over trade deals (especially NAFTA). This is why The Economist sees less of a left/right divide today and more of an open/close divide. Skepticism of trade and immigration wrapped in “power to the people” sentiments may be invigorating in rhetoric, but it’s asinine in practice. And it’s doing nothing more than riding the wave of voter anxiety. What’s worse, it’s hiding these politicians’ accumulation of power, attainment of status, and moral self-aggrandizement behind what Ginsberg so aptly calls “the veneer of public spiritedness.”

More Stuff

A classmate asked if I believed that politicians always acted in self-interest or if there were moral lines that some would not cross. In response, I pointed out that Simler and Hanson are largely arguing against what they see as the tendency for people to tiptoe around hidden motives and self-deception. It’s not that we’re only motivated by selfish motives. We just tend to gloss over them. But they are deeply embedded. Failing to acknowledge them not only has personal consequences, but public ones as well (their chapter on medicine is especially on point). I think we should consider moral motivations through all possible means available, including life experience and behavior. However, I think a healthy dose of skepticism is necessary. It can certainly help protect us against intentional deception. But perhaps more importantly, it helps protect us against unintentional deception. It’s easy to give more weight to life experience, moral principles, and the like when it’s a politician on “our side,” all while harshly judging those on “the other side” as unscrupulous. Political skepticism or cynicism can aid in keeping our own selfish motives and emotional highs in check. And it can lead us to seek out more information, improve our understanding, and refine our beliefs. Otherwise, we end up being consumed by our own good intentions and moral principles without actually learning how to implement these principles.

My classmate also put forth a hypothetical to get a feel for my position: if legislative districts were redrawn so that legislators now represented districts with a different ideological makeup, how many would change their positions on issues just to stay in power? Personally, I think we would see a fair number of politicians shift their position because it is more advantageous. However, there is considerable evidence that political deliberation with ideological opposites actually backfires. Political philosopher Jason Brennan reviews the evidence in chapter 3 of his book Against Democracy and finds that political deliberation:

- Undermines cooperation

- Exacerbates conflict when groups are different sizes

- Avoids debates about facts and is instead driven by status-seeking and positions of influence

- Uses language in biased and manipulative ways, usually by painting the opposition as intrinsically bad

- Avoids controversial topics and sticks to safe subjects

- Amplifies intellectual biases

There’s more, but that should make my point. So even if some politicians did not flip flop in their newly-drawn districts, the above list should give us pause before we conclude that their doubling down is proof of disinterest in status or moral grandstanding.

I certainly believe that people have moral limits and lines they will not cross. My skepticism (which I prefer to the word cynicism, but I’m fine with interchanging them) is largely about honest self-examination and the examination of others. For example, consider something that is generally of no consequence: Facebook status updates. My Facebook feed is often full of political rants, social commentaries, and cultural critiques. Why do we do that? Why post a political tract as a status? It can’t be because of utility. A single Facebook status isn’t going to fix Washington or shift the course of society. It’s unlikely to persuade the unsaved among your Facebook friends. In fact, it’s probably counterproductive given our tendency for motivated reasoning. When we finally rid ourselves of the high-minded rationales that make next to zero sense, we find that it boils down to signaling: we are signaling our tribe. And that feels good. We get “Likes.” We get our worldview confirmed by others. We gain more social capital as a member of the group. We even get to moral grandstand in the face of that friend or two who hold (obviously) wrong, immoral beliefs. Sure, some of it may be about moral conviction and taking a stand. That certainly sounds and feels better. But I think we will all be better off if we realize that’s really what those behaviors are about: sounding and feeling good. And I think our politics will be better off if we apply a similar lens to it.

And More Stuff

A classmate drew on Dan Ariely’s work to argue that people–including politicians–have a “personal fudge factor“: most people will cheat a little bit without feeling they’ve compromised their sense that they are a “good person.” When people are reminded of moral values (in the case of the experiments, the honor code or 10 commandments), they don’t cheat, including atheists. So while politicians may compromise their values here and there, they still have a moral sense of self that they are unlikely to violate.

In response, I pointed out that a registered replication report last year was unable to reproduce Ariely’s results. That doesn’t mean his results were wrong, just that we need to be cautious in drawing any strong conclusions from them.

When discussing his priming with the 10 Commandments on pg. 635, Ariely references Shariff and Norenzayan’s well-known 2007 study. This found that people behave more prosocially (in this case, generosity in experimental economic games) when primed with religious concepts. They offered a couple explanations for this. One hypothesis suggested that “the religious prime aroused an imagined presence of supernatural watchers…Generosity in cooperative games has been shown to be sensitive to even minor changes that compromise anonymity and activate reputational concerns” (pg. 807). They then cite studies (which later studies confirm) that found people behaving more prosocially in the presence of eye images. “In sum,” the authors write, “we are suggesting that activation of God concepts, even outside of reflective awareness, matches the input conditions of an agency detector and, as a result, triggers this hyperactive tendency to infer the presence of an intentional watcher. This sense of being watched then activates reputational concerns, undermines the anonymity of the situation, and, as a result, curbs selfish behavior” (pg. 807-808). In short, religious priming makes us think someone upstairs is watching us. This has more to do with being seen as good.

However, religious priming obviously doesn’t work for the honor code portion. Yet, Shariff and Norenzayan’s other explanation is actually quite helpful in this regard: “the activation of perceptual conceptual representations increases the likelihood of goals, plans, and motor behavior consistent with those representations…Irrespective of any attempt to manage their reputations, subjects may have automatically behaved more generously when these concepts were activated, much as subjects are more likely to interrupt a conversation when the trait construct ‘‘rude’’ is primed, or much as university students walk more slowly when the ‘‘elderly’’ stereotype is activated (Bargh et al., 1996)” (pg. 807). Being primed with the “honorable student” stereotype, students were more likely to behave honorably (or honestly).

In short, Ariely’s study I think shows a mix of motivations when it comes to behaving morally: (1) maintaining our self-concept as a good person, (2) fear of being caught and having our reputation (and the benefits that come with along with it) damaged, and (3) our susceptibility to outside influence.

My point about moral grandstanding is not that we should interpret all behaviors by politicians through the lens of self-delusion and status seeking. But being aware of it can help us cut through a lot of nonsense and avoid being swept up in a collective self-congratulation. To quote Tosi and Warmke, “thinking about grandstanding is a cause for self-reflection, not a call to arms. An argument against grandstanding shouldn’t be used as a cudgel to attack people who say things we dislike. Rather, it’s an encouragement to reassess why and how we speak to one another about moral and political issues. Are we doing good with our moral talk? Or are we trying to convince others that we are good?” And as philosopher David Schmidtz is said to have quipped, if your main goal is to show that your heart is in the right place, then your heart is not in the right place.