Economist Jonathan Portes has an excellent summary of the research on immigration’s effects in the UK:

- Employment: “To the considerable surprise of many economists, including me, there is now a clear consensus that even in the short-term migration does not appear to have had a negative impact on the employment outcomes of UK natives. Studies have generally failed to find any significant association between migration flows and changes in employment or unemployment for natives (see, for example, BIS 2014 for a review). Since 2014, the continued buoyant performance of the UK labour market has further reinforced this consensus. Rapid falls in unemployment, now down to just over 4%, have been combined with sustained high levels of immigration. Nor is there any evidence that immigration has impacted the employment prospects of specific groups such as the young or unskilled. Crudely, immigrants are not taking our jobs – the lump of labour fallacy, that the number of jobs or vacancies in the economy is fixed (which generally refers to the medium to long term) turns out to be a fallacy in the short term as well.”

- Wages: “While the evidence on wage impacts is less conclusive, the emerging consensus is that recent migration has had little or no impact overall, but possibly some, small, negative impact on low-skilled workers. Dustmann et al. (2013), using UK LFS data for the period 1997-2005, find that immigration put a downward pressure on the wages at the bottom of the distribution (below the 20th percentile), while the effect on the rest of the distribution (in particular above 40th percentile) is positive. Their estimates show that a 1% increase in the foreign-born/native population ratio leads to an increase of between 0.1% and 0.3% in average wages.”

- Productivity: “Immigrants’ skills may complement those of natives. A number of papers support this hypothesis: for example, Barone and Moretti (2011) found that low-skilled migration increased the labour force participation of highly skilled native women; Peri and Sparber (2009) and Foged and Peri (2016) found that low-skilled migration increased the wages of native low skilled workers. In particular, they argue that natives may have a comparative advantage in jobs with more communication-intensive tasks with respect to foreign workers, and that immigration ‘pushes’ low-skilled natives to occupations with a higher intensity of such skills, increasing the level of specialisation in the economy and hence productivity, as signalled by the corresponding increase in wages. Immigration might also influence the level of human capital in the economy, either directly if immigrants have high educational attainment (Kerr and Lincoln 2010, Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle 2010), or indirectly by increasing the incentive on natives to acquire human capital. Some evidence (Hunt 2017, McHenry 2015) suggests that increased low-skilled immigration increase school performance and outcomes for US natives…Looking at the service sector, Ottaviano et al. (2015) show that a 1% increase in immigrants’ concentration in local labour markets is associated with a 2% to 3% rise in labour productivity, measured as gross value added per worker, mainly as a result of the cost-cutting dynamics implied by immigration-induced labour supply shocks. In addition, immigration represents a substitute for the import of intermediate inputs and is associated with an increase in exports to immigrants’ countries of origin. Rolfe et al. (2013) found that immigrants concentration within specific industries was associated with slight increases in productivity, but the impact was small. At the aggregate level, recent literature uses cross-country evidence to estimate the impact of migration on growth and productivity in advanced economies. Boubtane et al. (2015) find that migration in general boosts productivity in advanced economies, but by varying amounts; for the UK, the estimated impact is that a 1 percentage point in the migrant share of the working age population leads to a 0.4-0.5% increase in productivity. This is higher than in most other advanced economies and reflects the relatively high skill levels of migrants to the UK. Jaumotte et al. (2016) find that a 1% increase in the migrant share of the adult population results in an increase in GDP per capita and productivity of approximately 2%. This result is consistent across a variety of empirical specifications. Perhaps surprisingly, the estimated aggregate impacts of high and low skilled migration are not significantly different (although the distributional implications are very different). In a within-country perspective, Peri (2012), with a state-based analysis in US, finds that a 1% increase in immigration raises total factor productivity by 0.5%, mainly thanks to increased specialisation induced by immigrants’ inflows.”

- Fiscal: “Dustmann and Frattini (2014) found that recent migrants, especially those from the EU, had a more positive fiscal impact on average than natives. Of course, it is hardly surprising that young migrants in employment make an initial positive fiscal contribution; proper assessment of fiscal impacts requires a life-cycle perspective (Preston 2014). In this context, there are various reasons to expect the impact to still be positive (in particular, migrants tend to arrive after they have left compulsory, publicly financed education). However, a positive net impact on public finances at the national level does not preclude a significant impact on demand (and hence cost) at the local level, particularly if funding allocations do not adjust quickly (or at all) to reflect pressures resulting from migration (George et al. 2011). A notable recent example is the shortage of primary school places in some parts of the UK (especially London); this appears to be largely the result of poor planning on the part of central government, given the rise in the number of young children resulting from recent increases in migration (from both the EU and elsewhere). But broader concerns about the potential negative impacts on public services appear to be largely unsubstantiated: higher immigration are not associated, at a local level, with longer NHS waiting times (Giuntella et al. 2015); and in schools, increased numbers of pupils with English as a second language doesn’t have any negative impact on levels of achievement for native English speaking students (Geay et al. 2013). If anything, pupils in schools with lots of non-native speakers do slightly better.”

- Prices: “Frattini (2008) analyses the impact on tradable, non-tradable goods and services prices across UK regions over the period 1995-2006 and shows that immigration is associated with a fall in prices for non-tradeable goods and services, but a rise in the price of tradeables. Sá (2015) focuses on the impact on housing prices in UK local authorities from 2003 to 2010 and shows that immigration actually reduces house prices at a local level, since natives leave the area in response to high immigrant inflows; although this does not imply, of course, that immigration does not overall exert upward pressure on house prices at a national level.”

So what are the likely results of Brexit? He concludes,

The conclusion is that the reductions in migration resulting from Brexit are likely to have a significant adverse impact on UK productivity and GDP per capita. The broad scenarios (not forecasts) we depict imply that the negative impacts on per capita GDP will be significant, potentially approaching those resulting from reduced trade. By contrast, the increase in low-skilled wages resulting from reduced migration is expected to be, if at all, relatively modest.

In an

In an

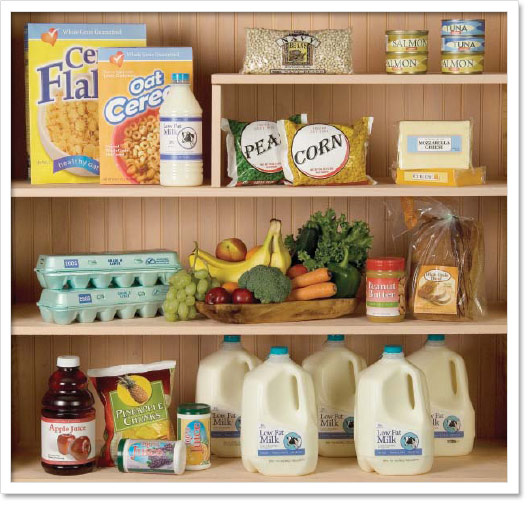

Some of the foods you can purchase through WIC.

Some of the foods you can purchase through WIC.