I’ve written about global income inequality in several past posts. As Nathaniel and I wrote in SquareTwo a few years ago,

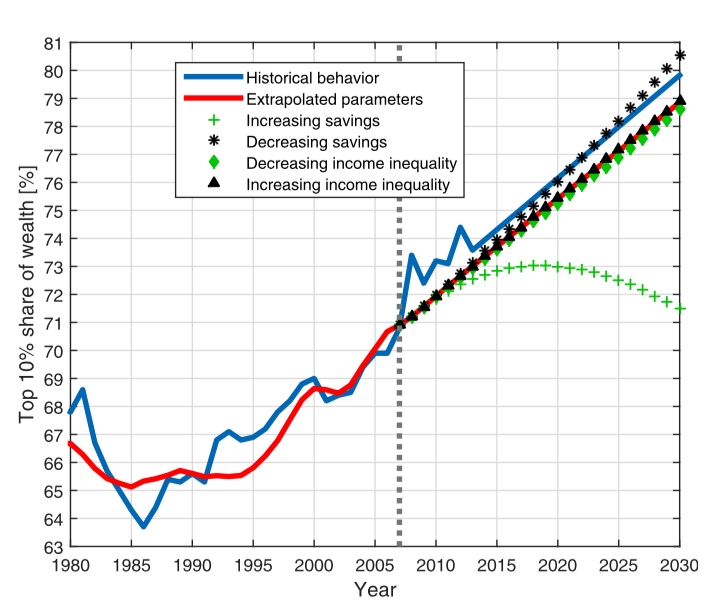

[W]ith the continual rise of the poor out of destitute poverty, it seems logical that global inequality would also be declining. Happily, recent evidence seems to supports the logic. As former World Bank economist Branko Milanovic put it, “[P]erhaps for the first time since the Industrial Revolution, there may be a decline in global inequality…For the first time in almost two hundred years—after a long period during which global inequality rose and then reached a very high plateau—it may be setting on a downward path.” Though cautious in his conclusions, Milanovic nevertheless finds that when population is factored into the data, the evidence demonstrates that the world became a “much better (“more convergent” or more equal) place” between 1980 and 2011. When country price levels (used to determine purchasing power) are factored in, a decline in global inequality can be seen over the past decade.

Several studies over the past few years have found that as the world poverty rates plummeted, so did global inequality. As one pair of researchers explains,

We can compute not only the world poverty rates and the poverty rates of any country or region, but also other statistics related to the distribution of income. For instance, we can compute the world gini coefficient, a measure of world inequality, for every year between 1970 and 2006. We show that world inequality measured by the gini fell from 67.6 to 61.2 (Figure 3), and similar declines in inequality can be shown for other inequality statistics, such as the mean logarithmic deviation, the Theil Index, and the Atkinson family of inequality indices.

While inequality is still high and increasing within countries, global inequality (between countries) has seen an unprecedented decline. “Even though the bulk of this decline is due to the performance of China and other Asian countries,” evidence shows “that a (weaker) declining trend survives even when these countries are excluded from the analysis.” Economist and Nobel laureate Friedrich Hayek noted that “after rapid progress has continued for some time, the cumulative advantage for those who follow is great enough to enable them to move faster than those who lead and that, in consequence, the long-drawn-out column of human progress tends to close up…[O]nce the rise in the position of the lower classes gathers speed, catering to the rich ceases to be the main source of great gain and gives place to efforts directed toward the needs of the masses. Those forces which at first make inequality self-accentuating thus later tend to diminish it.”

The above describes relative inequality. However, a more recent study shows that absolute inequality has increased.

As one of the researchers explains,

[T]ake the case of two people in Vietnam in 1986. One person had an income of US$1 a day and the other person had an income of $10 a day. With the kind of economic growth that Vietnam has seen over the past 30 years, the first person would now in 2016 have $8 a day, while the second person would have $80 a day. So if we focus on ‘absolute’ differences, inequality has gone up, while a focus on ‘relative’ differences suggests that inequality between these two people has remained the same.

Relative inequality indicators have been by far the most widely used in empirical economic analysis, but, based on economic theory and empirical evidence, it is far from clear that we should favour relative over absolute notions of inequality. The evidence suggests that many people do perceive absolute differences in incomes as being an important aspect of inequality (Amiel and Cowell 1992, 1999).

However, the authors concede,

Over the past 40 years, over one billion people around the world have been lifted out of poverty, driven largely by substantial growth in income in developing countries. While this growth has been accompanied by a striking rise in absolute inequality, it has also improved the lives of hundreds of millions of people. It is difficult to imagine how in practice such growth, and the associated poverty reduction, could have occurred without an increase in absolute inequality. There would be huge implications for the fight against global poverty if attempts were made to halt economic growth in order to appease absolute inequality. Instead, the policy emphasis should be on creating more inclusive growth with falling ‘relative’ inequality – these two goals are complementary.

Is it true, though, that it’s “far from clear that we should favour relative over absolute notions of inequality”? For example, most studies favor absolute poverty over relative poverty. Could the same case be made for absolute inequality? I’m not so sure. Branko Milanovic, one of the leading scholars on income inequality, provides the following reasons for preferring relative measurements in regards to inequality:

- Conservatism: “[R]elative income measures are conservative because they show no change in in equality in cases where absolute measures would show an increase (when all incomes go up by the same percentage) or a decrease (when they all go down by the same percentage). On in equality, which is a topic of considerable moral and political importance, and at times a very inflammatory topic indeed, we do not want to err in the direction of inflaming it further. Conservatism (in terms of measurement, not necessarily in terms of policy) is to be preferred.”[ref]Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016), 27.[/ref]

- Precision: “Think of the distribution as a balloon. As the balloon expands, the absolute distance between the points on the balloon increases. Focus on absolute distances presents the disadvantage that practically every increase in the mean (blowing up the balloon) could be judged to be pro-inequality. We would lose the sharpness with which we can currently distinguish between pro-poor and pro-rich growth episodes.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

- Relative Growth: “Growth is simply the relative increase in the first moment, and in equality is the relative increase in the second moment. The measures that we use to assess success or failure in economic development (relative change in GDP per capita) should be related to the measures we use to assess success or failure in distribution of resources (relative change in a measure of inequality). Focus on the absolutes in growth, as in inequality, would lead us to nearly always find that growth in rich countries, however small in percentage terms, would be greater than growth in poor countries, however huge. If the United States grew by 0.1 percent per capita annually, that growth would increase the absolute GDP per capita of each American by about $500, which is more than the GDP per capita of many African nations. Should we then deem Congo, in any given year, to have been as successful as the United States only if it doubles its per capita income— a feat that no human community has ever achieved in recorded history? So the logic of relativity that applies to growth should also apply to inequality.”[ref]Ibid., 28.[/ref]

- Personal Utility: “[F]or a person whose income is $10,000 to experience the same increase in welfare as a person whose income is $1,000, the absolute income gain ought to be ten times greater. In other words, one additional dollar will yield less utility, or seem less important, to a rich person than to a poor person. If we think that this is a reasonable assumption, we can then also interpret the data given in the growth incidence curve as changes in utility: an 80 percent income increase around the global median adds to the utility of people there more than a 5 to 10 percent increase in real income adds to the utility of the lower middle classes in rich countries (even if the absolute dollar gains of the latter may be larger). By this route too, we come to the conclusion that relative income changes are a more reasonable metric than absolute income changes.”[ref]Ibid., 29.[/ref]

While absolute measures in inequality may have their use, relative measures do a better job of complementing analyses of growth and poverty. In short, relative inequality provides a better framework by which to gauge standards of living.