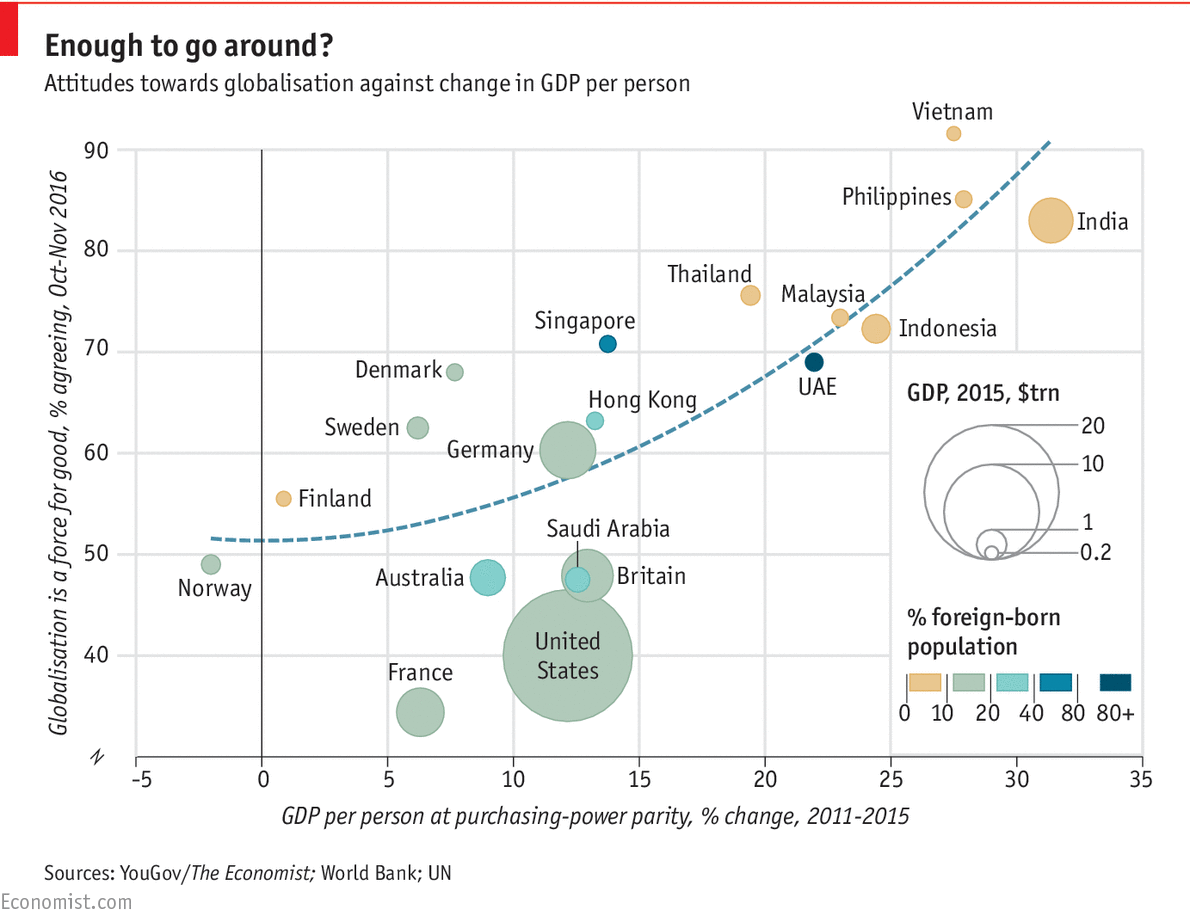

The Economist reports on a new YouGov poll that surveyed “19 countries to gauge people’s attitudes towards immigration, trade and globalisation. The data reveal a split between emerging markets and the West, which is increasingly turning its back on globalisation. Beset by stagnant wage growth, less than half of respondents in America, Britain and France believe that globalisation is a “force for good” in the world. Westerners also say the world is getting worse. Even Americans, generally an optimistic lot, are feeling blue: just 11% believe the world has improved in the past year.”

The chart above demonstrates that “countries with the fastest-growing economies tend to be more positive about globalisation. The French, Australians, Norwegians and Americans tend to oppose the idea of foreigners buying indigenous companies. But most Asians do not see a problem. Few in Hong Kong and Singapore would argue that their city-states should be self-sufficient, whereas most respondents in Indonesia, Thailand, India, the Philippines and Malaysia reckon that their countries shouldn’t have to rely on imports.” But “nationalism is especially pronounced in France, the cradle of liberty. Some 52% of the French now believe that their economy should not have to rely on imports, and just 13% reckon that immigration has a positive effect on their country. France is divided as to whether or not multiculturalism is something to be embraced. Such findings will be music to the ears of Marine Le Pen, the leader of the National Front, France’s nationalist, Eurosceptic party. Current (and admittedly early) polling has her tied for first place in the 2017 French presidential race.” There may even be some comfort for those concerned about growing anti-democratic sentiments. For one, these sentiments may not be as pronounced as often reported. Furthermore, the YouGov poll finds hope in younger generations:[ref]Though there is likely need for caution regarding this conclusion as well.[/ref]

While millennials tend to hold more left-wing economic views, they are far keener on the idea of globalisation, broadly conceived, thanks to their more positive attitudes towards multiculturalism. In America, 46% of those aged 18-34 think that immigrants had a positive effect on their country, compared with just 35% of those aged 55 and over. In Britain the generational gap is even bigger: 53% and 22%, respectively. And millennials were more optimistic in every country surveyed, save for Indonesia.

Let’s hope their left-wing economic views don’t devolve into anti-trade populism.

Following the results of November’s presidential election, I decided to read up on the social science on voter rationality. The first was Ilya Somin’s

Following the results of November’s presidential election, I decided to read up on the social science on voter rationality. The first was Ilya Somin’s

.gif)

A brand new

A brand new