Last week I published a post contrasting world-building between J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (hereafter: LotR) and the high fantasy genre that followed using Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive (which includes Way of Kings and Words of Radiance so far and which I’ll be calling just SA). The post sparked some fun and interesting discussion, but the comments (here and on Facebook) made me realize I could have been a little bit clearer about some aspects of the OP. In this post I’m going to use some simple illustrations and a few more examples (the Harry Potter and Hunger Games series) to try and provide that clarity.

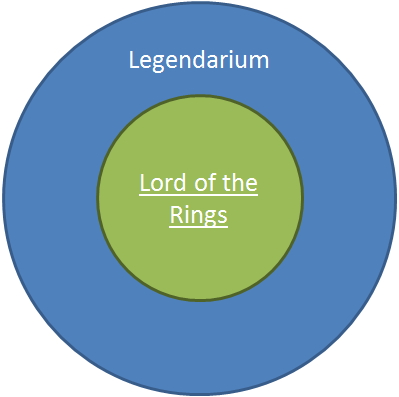

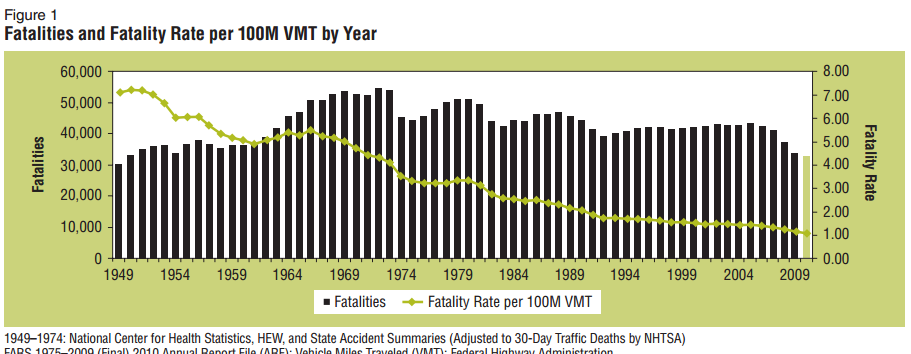

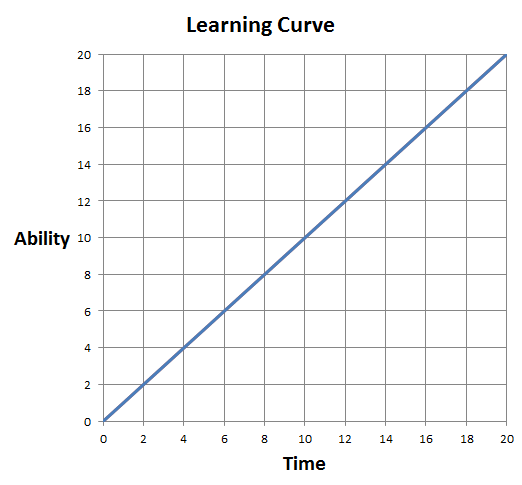

The image below depicts the difference between the setting in which LotR takes place (the blue region) and the aspects of the setting that are actually conveyed directly in the LotR itself (the green region).

To give an example of what I mean, consider the language Quenya. That’s one of the languages he invented[ref]it’s the language of the High Elves, but folks were speaking Sindarin by the time of LotR.[/ref], and he started work on it in 1910, more than 20 years before he started work on The Hobbit. By the time he started work on LotR, Quenya was largely complete. The entire language of Quenya (all the vocabulary, all the grammatical rules, and all the etymology that goes along with it) goes in the blue circle. Just those specific parts of Quenya (a few words, maybe whatever grammar was required for a phrase or sentence) that made it into the LotR go in the green circle. So the blue region is the entire setting (everything the author ever thought of) and the green region is just the parts of the setting that the author actually used directly in the story.

Obviously this isn’t an exact science, but what makes Tolkien’s example so helpful is that he actually made pretty details notes of his entire setting and it even has a name: the Legendarium. The fact that all his world building is collected in notes and papers that are pretty common knowledge (Christoper Tolkien used those notes to complete the manuscript for the The Silmarillion after his father’s death, for example) makes it particularly easy to envision the entire setting as something that is separate from the aspects of the setting that crop up in the LotR themselves.

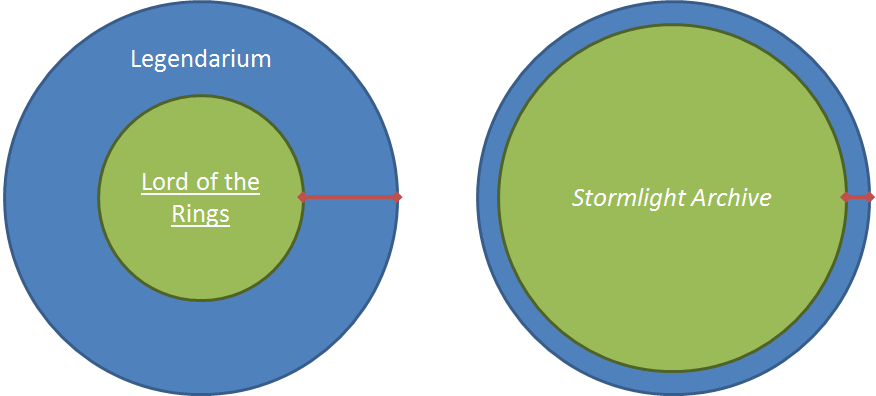

So that’s what my chart shows: the setting broken down into the parts that show up within the text (the green region) and then the other stuff that might be hinted at in the text, but isn’t actually there directly (the blue region). Here’s what I imagine the charts looking like for LotR and SA side by side:

The blue regions are sized identically because I don’t want to try and talk about who created more, Tolkien or Sanderson. They are both epic high fantasy authors, so they both write a lot. I suspect Tolkien created much more in his lifetime than Sanderson has created so far, but Sanderson may well surpass him. Who cares. The point is that they both do a lot of world-building so let’s just call it equal.

The difference, then, is that the proportion of Sanderson’s world-building for SA that shows up in SA is much, much higher than the amount of the Legendarium that shows up in LotR. That’s what the red lines are showing you: Tolkien’s excess world-building is thick. Sanderson’s excess world-building is thin.

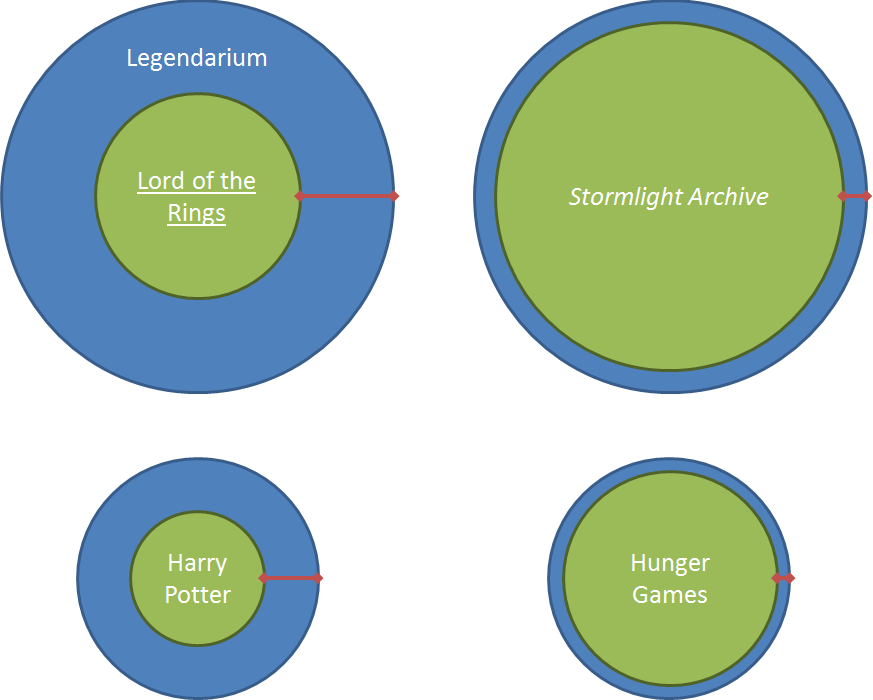

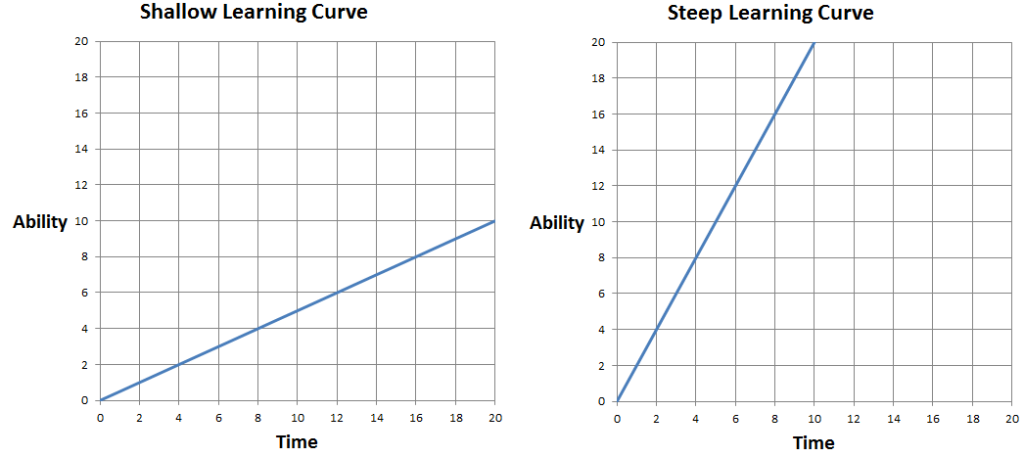

Before we talk too much about what that means, let me just throw up one more image. This one adds the Harry Potter and Hunger Game series to the mix.

I don’t want to get bogged down in the exact details of who did more world-building than whom, but I think it makes sense to say that the epic high fantasy authors (Tolkien and Sanderson) did more world-building than Rowling or Collins. This isn’t to say that they did better world-building. I’m on-record as thinking that J. K. Rowling’s world-building is total genius[ref]Long version. Short version.[/ref], but she didn’t do very much of it compared to Tolkien or Sanderson.

So here’s the main point of this post: more world-building in aggregate (bigger blue circles) isn’t necessarily better, but thicker world building (more gap between the green circle and the blue circle) is better. And now the explanation/defense and some caveats.

I don’t think more world-building in aggregate is better because it’s really just a genre question. High fantasy does lots of world-building. Serious mystery novels and real-world thrillers do very little of it. Historical fiction does lots of it, but it’s research rather than invention, so it’s a very different kind of world-building. The point is, you should create enough of a world for your story to live in. If your story requires a relatively small setting or occurs in the real world, then you don’t need to do a lot of world-building. If your story has a big scope and takes place in a fantasy world, then you do need to do world-building. More, in aggregate, isn’t better. It’s a matter of fitting the world-building to the story.

So why is it bad to have only a small amount of world-building “left over” as it were? The primary answer is that, especially in stories that take place in fictional worlds, you want to preserve a sense of immersion in the world. Excess world-building helps you do that in multiple ways. The most important is that referring to events and locations that have an existence independent of the main narrative is a really powerful signal to readers that “this is a real place where lots of things happened, not just a setting I threw together for this one particular story.” When every single aspect of your story ends up being required for the plot, you strain a reader’s credibility in the same way that having too many coincidences in the plot strains credibility: it doesn’t seem natural. Your story should have places your characters don’t as much or care as much about as other people in the universe do because otherwise you’re implying that everything in the world exists merely in service of the characters. Which feels horribly fake.

The other ways are less direct, but still relevant. The work of doing more world-building is a kind of quality control on what you do show. I think even non-linguists can be struck by the way the language (especially via proper names) in LotR broke down consistently among ethnic and political groups. Most fantasy writers just pick similar-sounding names without worrying about complex etymologies, but the risk of sounding like just a jumble of made up syllables is higher when you’re just throwing out a jumble of made up syllables. Also, leaving a bigger gap between what you create for the world and what you show in the story means you have more freedom with your narrative. If you feel like you have to show off everything you create, you can end up bending the plot so that it becomes more of a guided tour of your brilliant creation rather than an independent story.

So, just to recap the graphic above, Collins does a bad job of world-building because even though her story is limited in scope, she did the absolute bare minimum to create even the relatively small setting she needed. Sure, her world building is pretty terrible in general (that’s pretty well-known), but even if you set aside the stuff that doesn’t make sense the problem remains that she just reskinned the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur with the slimmest trappings of a generic sci-fi dystopia and called it a day. She does do a little bit when it comes to the culture of the Capital, but there’s nothing about the setting scientifically, linguistically, culturally (outside the Capital), historically or in any other sense that would make you believe that this is anything other than a flimsy, disposable backdrop for her plot. In short: Collins didn’t create enough setting to fit her story.

Rowling also had a story with a pretty limited scope. Hogwarts, the Burrow, and the Ministry of Magic pretty much account for all the setting she needs. But Rowling did a good job of making the world fill lived in primarily through the inclusion of tantalizing books. Where Tolkien made the world seemed lived in by giving forgotten histories to all sorts of places (the Barrows, Weathertop, the Argonath just to name a few), Rowling made the world seemed live in by giving context to all the silly textbooks at Hogwarts. If you think about the number of times a book played a crucial role in Harry Potter, you’ll realize how important they were to the landscape. And the fact that their authors frequently showed up as minor characters or historical figures really deepened the sense in which these books were part of the world. Just like J. R. R. Tolkien, J. K. Rowling had plenty of material in her own Legendarium left over to make follow-up books that were based on books mentioned in the original series. There’s The Tales of Beedle the Bard, for example, and the new Harry Potter trilogy is going to be based off of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (which also exists as a book). J. K. Rowling was as profligate with the books she invented for the Harry Potter universe as Tolkien was with language or as Sanderson is with magical systems.

The SA suffers from the same basic problem as Hunger Games (not enough extra world-building) but for the opposite reason. He created plenty to tell the core story, but then he kept cramming more and more of hiw world-building into the narrative until there was barely anything left over. The end result is the same: there’s no sense of realism that comes from a reader perceiving that the world extends beyond the borders of the pages.

Tolkien, of course, is the gold standard. Although the scope of LotR is great, it is nowhere near the scale of the Legendarium from which it draws. My one wish for Sanderson—because I really do like SA—is that he would be willing to stop feeling the need to show off every idea he has in the narrative. It makes the story feel like a guided tour instead of an adventure.

First major caveat: we’re only looking at world-building. That’s just one aspect of what makes a work tick. There are all kinds of other factors: quality of prose, vibrancy of characterization, mastery of theme and tone, coherence of plot, etc. I’m not attempting to address those. This post together with the previous one are not an attempt to give some kind of comprehensive theory of fiction or high fantasy. They are not even a complete theory of world-building. One of the most important tricks that Tolkien uses, for example, that has nothing to do with green circles or blue circles is to demonstrate that actions in one work change the setting in ways that are felt in subsequent works. The best example of this is the way that Frodo stumbles upon the trolls in LotR that Bilbo had helped turn to stone in The Hobbit. The persistence of changes to the setting across works is a brilliant tool in world-building (and one I understand Sanderson may excel at) that falls totally outside the scope of this post.

Second major caveat: it’s possible that I’ve got the wrong frame of reference for Sanderson’s books. I have only read his SA series, but I am aware that all of the books he’s writing a linked up in a single world. Tolkien has the Legendarium. Sanderson has the Cosmere. That defense is not as strong as it first appears, however, because it increases the size of Sanderson’s setting substantially (the Cosmere is really big) but it also increases the size of his narrative because in addition to the two books in the SA, we’ve also got: Warbreaker, the Mistborn series, Elantris, White Sand, Dragonsteel, and others. In other words: I might be underestimating the scale of Sanderson’s setting, but only if I’m also underestimating the size of his narrative. This is because, unlike the relatively unrelated works of Tolkien, the whole point of the Cosmere is that all the books are actually part of one grand epic. In that case, you might have to draw a much bigger blue circle, but the green circle keeps on growing, too. You’re still let with a thin band. The problem doesn’t actually go away[ref]Of course because Sanderson is only in the early stages of a truly monumental undertaking I can’t be certain in my estimation. But that’s how things look today.[/ref].

So here’s where this leaves us—and I promise I’m done on this topic for the time being when I wrap this post up—the fundamental rule is that you want your world-building to be comfortably larger than what you’re actually going to use directly in the story you tell. This came naturally to Tolkien. Keep in mind he was working on Quenya twenty years before he started The Hobbit! I’m sure part of that was his personality, but it was also a matter of religious faith to him: world-building was a form of worship. So he did a lot of it. So, even though LotR is a big story, his setting was bigger.

High fantasy is particularly sensitive to the quality of world-building, but high fantasy authors since Tolkien have generally failed to get anywhere close to his mastery of it. Often, this is because they don’t do enough world-building. This makes sense, who wants to invest 20 years in world-building before they start a story they don’t even know if they will be able to publish or not? Sometimes it’s because they’re just not very good at it. But even when you get someone like Sanderson—someone who creates a lot and who does it quite well—they still can run into the trap of wanting to stuff all of that world-building into their story instead of leaving a nice, comfortable margin. If Sanderson included less of the world-building in the story, the narrative would have more focus and the world would feel more extensive and genuine.