This is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

A constant theme in several talks of the Saturday morning session of the April 1975 General Conference was spiritual transformation as a daily practice. For example, Sterling W. Sills borrowed from a previous talk to describe our rebirth(s) or “human reawakenings” (emphasis mine) Notice the plural. He notes that “no one is limited to merely two births [i.e., physical birth and baptism]…we can be born again as many times as we please. And each time we can be born better.” In one of my favorite quotes from his talk, he says,

In 1932, Walter Pitkin wrote a great book entitled Life Begins at Forty. But that is ridiculous. Life begins when we begin, and we may begin a new and better life every morning.

Someone once asked Phillips Brooks when he was born, and he said that it was one Sunday afternoon about 3:30 when he was 25 years of age, just after he had finished reading a great book. Just think how many thrilling, exciting rebirths we can have as we study the holy scriptures and as we fill our minds with the word of the Lord and get the spirit of righteousness into our hearts.

These multiple rebirths are meant to eventually lead us to “some future Easter morning” when “we may be born again into [God’s] presence to live with him in the celestial kingdom throughout eternity.”

The idea that rebirth is not a single event can also be found in Robert D. Hales’ talk: “I have learned from Joseph Fielding Smith, and have talked to young people, about the law of consecration. It is not one particular event; it is a lifetime, day by day, in which we all strive to do our best that we might live honorable lives, that we might live the best we can in the service of others…” Consecration is found in the scriptures, but its covenantal form takes place within the temple. I’ll return to this momentarily.

Mark E. Peterson provides a slightly different angle to Sabbath day worship:

What can we do to protect ourselves under these hazardous circumstances? How can we better help our young people to remain unspotted from the world? The Lord gives us the answer, and says that it can be done by sincerely observing the Sabbath day. Most people have never thought of it in this way, but note the words of the Lord in this regard: “That thou mayest more fully keep thyself unspotted from the world”—note these words—“that thou mayest more fully keep thyself unspotted from the world, thou shalt go to the house of prayer and offer up thy sacraments upon my holy day.” (D&C 59:9.)

In short, “we are commanded to change our usual routine and go to church and worship God on the Sabbath.” I think the comments on consecration (and, by implication, the temple endowment) and Sabbath day observance are important. These practices interrupt our daily routine–interrupt our participation in what philosopher James K.A. Smith calls “secular liturgies”[ref]I’ve mentioned Smith’s work before. I’m finishing up his Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009) from which this term comes[/ref]–and reorient our hearts toward the kingdom of God. Our daily “cultural practices and rituals” are, according to Smith, “liturgies…We need to recognize that these practices are not neutral or benign, but rather intentionally loaded to form us into certain kinds of people–to unwittingly make us disciples of rival kings and patriotic citizens of rival kingdoms.”[ref]Desiring the Kingdom, 90-91.[/ref] Mormon philosopher JamesE. Faulconer says of the temple endowment,

Those participating in Mormon temple worship do not merely hear the story told in the ritual or watch someone ritually reenact it. They take part in the reenactment, moving from place to place, performing specified actions as part of the story. Ritual participants memorialize Adam and Eve and the founding events of the Christian human narrative by reenacting the story of Creation, Garden, Fall, and life in the world…Having ritually become Adam or Eve, each celebrant finds himself or herself identified in a symbolic order given by the Father and mediated by the Son, an ordering of not just individual lives, but of the cosmos and the community, as directed by and toward God…The celebrant acts out the story and, returning to the temple to do proxy work for the dead, acts it out again and again, doing the ritual for others and becoming more and more ingrained in its celebration. In doing so he lives and relives the founding story that makes sense of human life. The celebrant ties the memorialized past of Adam and Eve to his present, making that present into something new through the memorialized link…The Mormon commemoration of Adam and Eve serves a critical function similar to the Jewish celebration of the Sabbath or of Passover: it recalls to its participants events in history that define who they are and how they should be in the world, and it does so by putting those events into a narrative of self–and communal–identity that is ordered by God. Remembering the past of the Creation and the Fall serves to assure that celebrants will live int he world in the ways required by the order of Creation and Fall. Taking part in the temple ritual, the celebrant becomes part of the divine narrative, no longer merely an individual cut off from God.[ref]James E. Faulconer, “The Mormon Temple and Mormon Ritual,” in The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism, ed. Terryl L. Givens, Philip L. Barlow (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 202-204.[/ref]

Sabbath observance can offer similar reorientation. As I’ve written elsewhere,

There are two major strands of thought found in the scriptures regarding the reasons for the Sabbath. The first largely dominates the books of Genesis and Exodus and hearkens back to the Creation. As we read in Exodus, “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy…For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day, and hallowed it” (Ex. 20:8,11; cf. Gen. 2:2; Mosiah 13:16). Scholars have recognized for some time that the sequence and literary structure of Genesis 1 parallels that of ancient Near Eastern temple building, thus depicting the Creation as a cosmic temple (for fruitful scripture study, try comparing Genesis 1 to the building and dedication of the Tabernacle or Solomon’s temple). Within this context, God resting makes much more sense. “Deity,” explains Wheaton professor John Walton, “rests in a temple, and only in a temple. This is what temples were built for [in the ancient Near East]. We might even say that this is what a temple is—a place for divine rest.” With Genesis 1 as a temple text, it is worth noting that the Sabbath is the first mention of “holiness” in scripture and was later put on par with the temple itself: the Sabbath became a sanctuary or temple in time, while the temple became a Sabbath in space. This is why the temple and the Sabbath could be profaned in similar ways. In summary, the first interpretation of the Sabbath entails Creation, divine rest, and holiness.

The second train of thought is found mostly in Deuteronomy and the later prophets. The Deuteronomist version of the commandment reads, “Keep the Sabbath day to sanctify it…And remember that thou was a servant in the land of Egypt, and that the Lord thy God brought thee out of thence through a mighty hand and by a stretched out arm: therefore the Lord thy God commanded thee to keep the Sabbath day” (Deut. 5:12,15). This follows an admonition in which the entire Israelite household is told to cease from labor, including servants, foreign guests, and even animals (vs. 14). The reminder and celebration is that of liberation and the Sabbath itself acts “as an affirmation of human freedom, justice, and equality” by providing rest for all living beings. Therefore, the second interpretation is about remembrance, deliverance, and (given its connection to other practices such as the sabbatical years and Jubilee) social justice.[ref]References can be found in the link.[/ref]

These rituals and practices help shape our habits and desires. As we participate in them, our daily choices and routines will change as well. Multiple rebirths will occur as the natural man slowly dies. Then we will become “saint[s] through the atonement of Christ the Lord” (Mosiah 3:19).

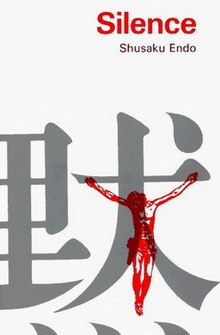

I bought Shūsaku Endō’s classic

I bought Shūsaku Endō’s classic

I’ve been a fan of British philosopher Roger Scruton ever since I stumbled on his BBC documentary

I’ve been a fan of British philosopher Roger Scruton ever since I stumbled on his BBC documentary