I was reading a Facebook thread recently in which a commenter was complaining about Walmart’s supposedly “evil” business practices and low wages compared to, say, Costco. This same commenter then advocated for the now-popular $15 minimum wage. Readers of Difficult Run are well aware that some of us here have little love for minimum wage laws. Setting aside the reasons Walmart and Costco might pay differently or the net positive effects of Walmart on the economy, I’m just going to point to two recent San Francisco Federal Reserve publications by UCI economist David Neumark. The first summarizes the current state of research on the employment effects of the minimum wage:

Many studies over the years find that higher minimum wages reduce employment of teens and low-skilled workers more generally. Recent exceptions that find no employment effects typically use a particular version of estimation methods with close geographic controls that may obscure job losses. Recent research using a wider variety of methods to address the problem of comparison states tends to confirm earlier findings of job loss. Coupled with critiques of the methods that generate little evidence of job loss, the overall body of recent evidence suggests that the most credible conclusion is a higher minimum wage results in some job loss for the least-skilled workers—with possibly larger adverse effects than earlier research suggested.

As for recent increases in the minimum wage, Neumark makes the following estimate:

Thus, allowing for the possibility of larger job loss effects, based on other studies, and possible job losses among older low-skilled adults, a reasonable estimate based on the evidence is that current minimum wages have directly reduced the number of jobs nationally by about 100,000 to 200,000, relative to the period just before the Great Recession. This is a small drop in aggregate employment that should be weighed against increased earnings for still-employed workers because of higher minimum wages.

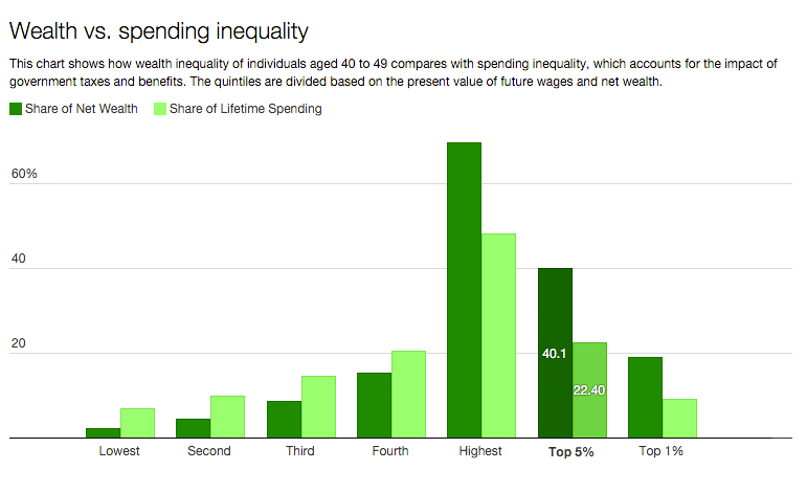

The second brief looks at the minimum wage’s effectiveness in reducing poverty and inequality. There are a couple complications:

One complication is research pointing to employment declines from minimum wage increases (see Neumark 2015), which means raising wages for some people must be weighed against potential job losses for others. In this case, whether a higher minimum wage on net helps poor and low-income families depends on the specific pattern of employment effects for different family types.

A second complication is that mandating higher wages for low-wage workers does not necessarily do a good job of delivering benefits to poor families. Of course, worker wages in low-income families are lower on average than in higher-income families. Nevertheless, the relationship between being a low-wage worker and being in a low-income family is fairly weak, for three reasons. First, 57% of poor families with heads of household ages 18–64 have no workers, based on 2014 data from the Current Population Survey (CPS). Second, some workers are poor not because of low wages but because of low hours; for example, CPS data show 46% of poor workers have hourly wages above $10.10, and 36% have hourly wages above $12. And third, many low-wage workers, such as teens, are not in poor families (Lundstrom forthcoming).

Considering these factors, simple calculations suggest that a sizable share of the benefits from raising the minimum wage would not go to poor families.

Both briefs are worth reading. Check them out. For me, it all goes back to what Thomas Sowell says: “There are no solutions; there are only trade-offs.”[ref]Sowell, The Vision of the Anointed: Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 142.[/ref]

Regular readers of Difficult Run know that research on marriage and family structure is a

Regular readers of Difficult Run know that research on marriage and family structure is a

I was lucky enough to meet BYU history professor J. Spencer Fluhman last year when he

I was lucky enough to meet BYU history professor J. Spencer Fluhman last year when he