This is a common rallying cry among Americans (e.g., Bernie Sanders) who are disturbed by income inequality in the U.S. and the supposed excesses of capitalism. So what can the United States learn from Sweden? Swedish author Johan Norberg writes,

As a native of Sweden, I must admit this makes me Feel the Bern a bit. Sanders is right: America would benefit hugely from modeling her economic and social policies after her Scandinavian sisters. But Sanders should be careful what he wishes for. When he asks for “trade policies that work for the working families of our nation and not just the CEOs of large, multi-national corporations,” Social Democrats in Sweden would take this to mean trade liberalization—which would have the benefit of exposing monopolist fat cats to competition—not the protectionism that Sanders favors.

In fact, when President Barack Obama visited Sweden in 2013, the three big Swedish trade unions sent him a letter requesting a meeting. Their agenda: a discussion of “how to promote free trade.” The chairman of the largest Social Democratic trade union scolded the American president for his insufficient commitment to the free flow of goods.

Norberg acknowledges that Sweden is “still-high public spending and high taxes, at least compared to the U.S….The governments provide the citizens with health care, child care, free colleges, and subsidized parental and medical leave. We Scandinavians have our quarrels with these systems and how they function, but at least they have not ruined our societies; indicators of living standards and health are impressive.” So how come this amount of government services doesn’t cripple the economy? Norberg explains,

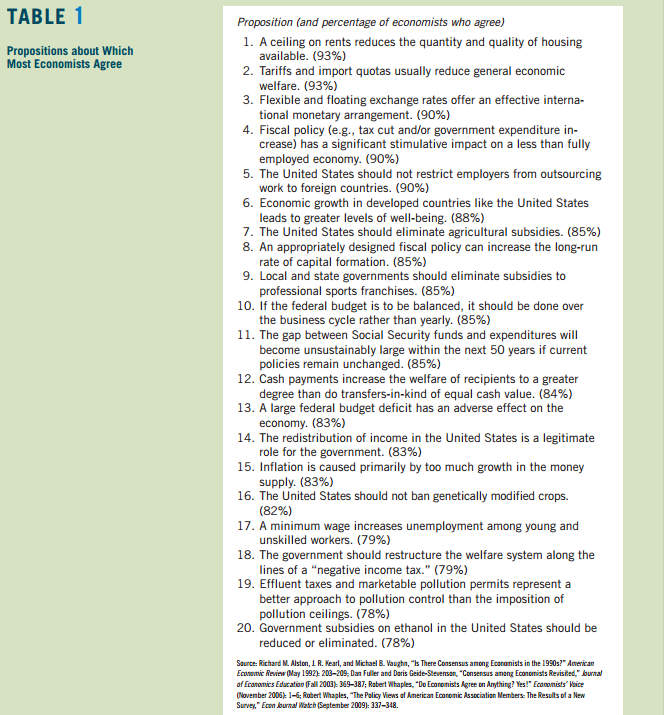

One reason is that we compensate for them with a more open economy than others. In the summary Fraser Institute rankings, Sweden and Denmark are more economically free than the United States when it comes to legal structure and property rights, sound money, free trade, business regulation, and credit market regulations. We don’t have the multitude of occupational licensing laws that block competition in the United States.

We also pay for the welfare state in a fairly brutal way, but one that doesn’t hurt production as much: by squeezing the poor and the middle class. Unlike the rich, poor and middle-class people don’t flee or dodge when they’re taxed aggressively.

The Social Democrats knew all along that they couldn’t fund such a generous government by taking from the rich and the businesses—there are too few of them, and the economy depends on them too much. So Sweden and Denmark take in lots of revenue via highly regressive value-added taxes at a normal rate of 25 percent of sales—the only tax where the rich and poor pay exactly the same amount in kronor. On the other hand, the corporate tax is just 22 and 23.5 percent respectively, compared to the U.S. rate of 35 percent.[ref]Check out this analysis of the Scandinavian tax systems at the Tax Foundation.[/ref]

In fact, rich people in Sweden enjoy several economic advantages not offered to their lower-class counterparts. Sweden always admitted very generous tax deductions for capital costs. Labor regulations are tailored to benefit big companies. To attract highly educated specialists from abroad, Sweden now has a beneficial “expert tax” for them, which shields 25 percent of their wages from taxation for a three-year period. “Sure, it is unfair, but we have no better solution,” the Social Democratic minister of finance said in 2000, when he implemented special tax exemptions for individuals and families who owned a large share of a listed company.

Unlike Sanders, Scandinavian socialists have concluded that you can have a big government or you can make the rich pay for it all, but you can’t do both.

The shape of welfare state also has roots in Swedish culture:

Two Scandinavian economists, Andreas Bergh and Christian Bjørnskov, have documented that a high degree of trust is an old legacy, and that descendants of those who emigrated from Scandinavia 100 years before the welfare state are also more trusting. Their conclusion is that trust in others and social cohesion creates the welfare state rather than the other way around, since it is more tempting to give power to politicians and money to strangers if you believe that they are decent people who would never cheat the system.

Scandinavians have always frowned on those who take money they are not entitled to. Sweden is, after all, the country where the leading candidate for prime minister in 1995 had to resign because it was revealed that she had used her official credit card to pay for some small private expenses, even though she always, every month, paid the credit card debt herself.

When asked, “Under what circumstances is one justified in accepting government benefits to which one is not entitled?” in 1991 and 1998, the Nordics led the world in saying “never.” (Only Malta says it is more upstanding, and a brief canvass of Maltese of my acquaintance suggests that they are rather likely to have lied on the survey.) Oh, and the United States is 16th, lower on the list than even the Italians.

Unfortunately, Sweden has recently seen “increased unemployment among immigrants. Now the employment gap between natives and foreign-born in Sweden is twice the European Union average, even though we express less racist and discriminatory attitudes than others. In response, Swedish politicians have recently decided to abandon liberal immigration policies and do whatever they can to scare people away. It was easier to have a one-size-fits-all approach when we were all alike, from the same background, with the same faith and attitude and a similar education. We need a more flexible model now that we are becoming a little bit more like…well, the United States.”

Economist Andreas Bergh mentioned above has documented the economic history of Sweden in hopes of answering the following questions:

- How did Sweden become rich?

- What explains Sweden’s high level of income equality?

- What were the causes of Sweden’s problems from 1970 to 1995?

- How is it possible that Sweden, since the crisis of the early 1990s, is growing faster than most EU countries despite its high taxes and generous welfare state?

His conclusions?

In many aspects, Sweden is not very different from other countries. The accelerating economic growth in Sweden around 1870 was most likely largely a result of liberalizations and well-functioning capitalist institutions. In this respect, there is no Swedish exceptionalism.

When it comes to equality, the most important conclusion is that most of the decrease in income inequality in Sweden occurred before the expansion of the welfare state. A number of seemingly unrelated reforms, such as land reforms, school reforms and the occurrence of unions and centralized wage bargaining, are likely explanations. Interestingly, at least parts of gender equality in Sweden seem to be an unintended consequence of the need to increase labor supply by using women in the workforce.

Thus, when it comes to the roots of prosperity and equality, the lessons from Sweden are not very different compared to the lessons from mainstream institutional economics: Well-functioning capitalist institutions, especially property rights and a non-corrupt state sector, promotes prosperity. Primary schooling, risk sharing social insurance schemes and labor unions contribute to a more equal distribution of income (pg. 21).

He notes that Sweden’s lagging economy between 1970 and 1995 was due to a

combination of unsuccessful macro-economic policies and a very generous welfare state…During the period of lagging behind, excessive state interventionism hampered structural adjustment and economic development in general. The economy was much less capitalist, rules were unstable, policy unpredictable, and work incentives were weakened by the design of taxes and benefits. This leads to the conclusion that to successfully combine a large welfare state with economic growth, macroeconomic factors are crucial and a high degree of economic openness may actually foster policies that promote competitiveness. Analyzing the fact that Sweden was ranked the second most competitive country in the world according to the Global Competitiveness Index 2010–2011 (just slightly behind Switzerland). Eklund et al. (2011) emphasize the role of market deregulations, inflation control and stricter budget rules – but also some lowering of taxes and benefit levels. The upshot is that the policy implications from the case of Sweden are hard to classify along a simple right-left scale: the welfare state seems to survive because it coexists with high levels of economic freedom and well-functioning capitalist institutions (pg. 22).[ref]You can read about the Swedish reforms since the 1990s here.[/ref]

So, be like Sweden. But be like it in the right ways.