There was another school shooting yesterday, this time at a community college in Oregon. There are all kinds of rumors and arguments flying around Facebook. For the most part, that just makes me want to turn off my computer for the day. But there is one thing I want to share first.

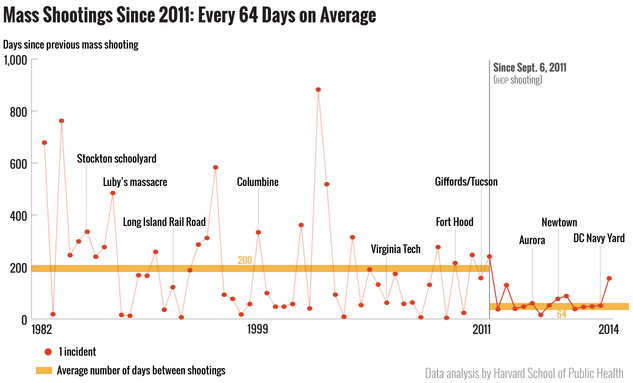

Almost exactly one year ago, Mother Jones published an article summarizing research concluding that “Rate of Mass Shootings Has Tripled Since 2011.” I’ve read the research claiming that the rate has actually not increased and, after reading the article in Mother Jones, I am convinced that this new research is correct. The rate of mass shootings (“attacks that took place in public, in which the shooter and the victims generally were unrelated and unknown to each other, and in which the shooter murdered four or more people”) has increased dramatically.

The data strongly indicates that “the underlying process has changed.” Meaning: something is different now than prior to 2011 that is leading to this increased rate of mass shootings.

Gun laws are not a plausible explanation because they have not changed significantly (at the federal or at the state level) during this time frame.[ref]The Federal Assault Weapons Ban did expire in 2004, but not only is that too remote from 2011 to be a plausible cause of the shift, but the reality is that nearly all of these attacks are committed with handguns and other weapons that were not affected one way or the other by the ban.[/ref] That statement is not an argument either for or against changes to existing gun laws. Just because gun laws didn’t cause the rate of attacks to increase does not mean that newer, tighter gun laws couldn’t in theory prevent some of these attacks. This post is not about gun control one way or the other. It is about something else.

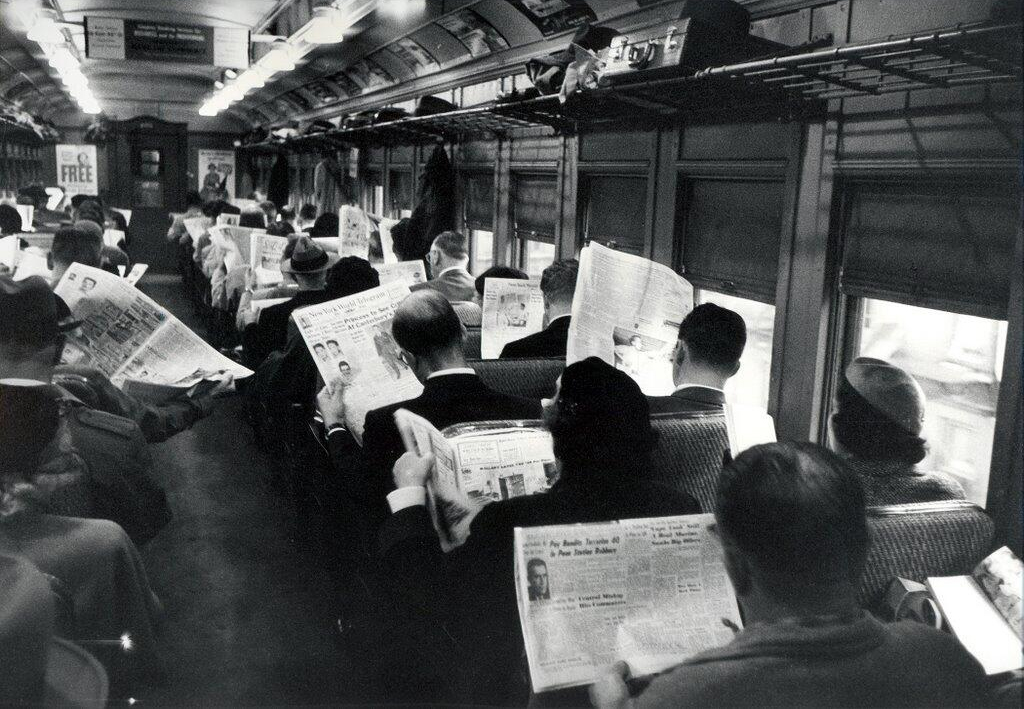

I have argued strongly that the way we cover these attacks is a major factor in encouraging future attacks.[ref]Here, here, and here are some examples.[/ref] The media leads with front-page photos of the killers, burns their names into the national consciousness, and implicitly ranks the tallies of their victims like a perverse score board and we the American people eat it up. We tune in, we click links, we debate, and again and again and again we repeat the killers’ names.

There is no hard data linking media coverage to the rate of killings, and due to the nature of these events there probably never will be. But the circumstantial evidence is quite strong. These killers often (not always, but often) talk about their desire for fame, for attention, for a sense of affirmation that their lives matter, and they know how to get that recognition because the media has promised to put their names and likenesses up in neon lights if they are willing to kill enough people to earn it.

This time is no exception. As the Daily Beast notes, the most recent killer paid close attention to media coverage of the last sensationalized murder (when a disgruntled former news anchor killed two of his old colleagues on live television) and wrote just over a month ago:

On an interesting note, I have noticed that so many people like him are all alone and unknown, yet when they spill a little blood, the whole world knows who they are. . . A man who was known by no one, is now known by everyone. His face splashed across every screen, his name across the lips of every person on the planet, all in the course of one day. Seems the more people you kill, the more you’re in the limelight.

Read that. Look at the Mother Jones chart again. Is the sudden increase in the rate of killings really that surprising? This is a textbook example of a positive feedback loop: each successive mass shooting elevates the topic in our national consciousness, leading to more and more coverage, and that coverage in turn motivates more and more killers to take their shot at “the limelight.” The question is: how long are we going to allow this to continue? Have we gotten our fill yet?

There are signs that we have. The Daily Beast article is a wonderful example whose time has come. This is the headline: Forget Oregon’s Gunman. Remember the Hero Who Charged Straight at Him. The article does not mention the full name of the killer. It does not include a photo of him. It does not make him into a star. Instead, it focuses on Chris Mintz, an army veteran who was shot five times during the attack while charging the killer head on in an attempt to stop the attack.[ref]Update: Another article from NBC says that he was shot seven times.[/ref] It was Mintz’s son’s birthday, and that is what he kept repeating to himself again and again as another student (training to be a nurse) held his hand and prayed with him while they waited for the ambulances to arrive. Mintz is still alive, recovering in the hospital after surgery, although a friend says Mintz may have to learn to walk again.

This is the kind of coverage we need. Michaely Daly and Kate Briquelet, who wrote the article, should be commended. The subtitle of the article is simply “reward courage,” and that’s what he did. While journalists all over the country are going to start the inevitable scramble to unearth every last rumor and irrelevant detail about the killer’s life and fill articles with inane quotes from neighbors and fellow students, Daly instead interviewed the friends and family of a heroic father who risked his life in an attempt to stop a murderer. The Daily Beast should be commended for running this article. Instead of plastering the Internet with photos of an attention-seeking murderer (which is to say: rewarding a murderer), they ran photos of Mintz like this one as their cover image:

I’m not trying to short-circuit the debate on gun control that will follow. Gun control is an important issue and worth our time to discuss. I’m also not trying to advocate for censorship or burying the truth.

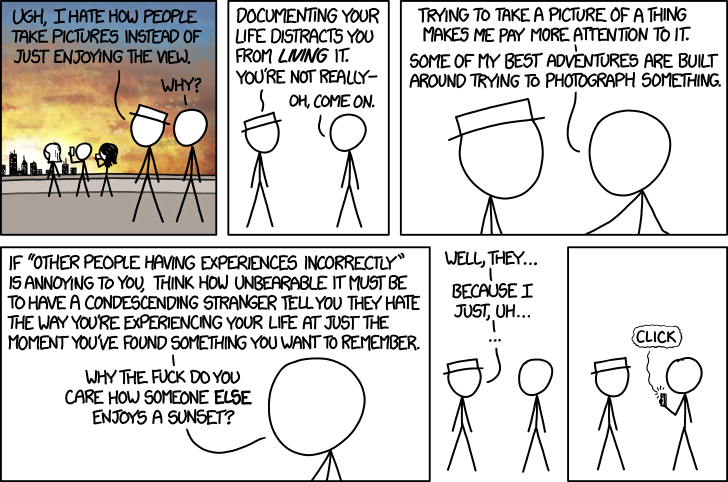

I’m just saying maybe we don’t need so much coverage so quickly so focused on the bad guy. Maybe we write about the good guys, like Daly did. Maybe we just have a little less coverage and spaced out a little more. Right now, 1/2 of what you read about this event is going to turn out to be false anyway. Why are we so desperate to study rumors? Do we really need to watch more completely uninformative aerial footage of hospitals and cars with blinking lights while reporters desperately peddle rumors, guesses, and ignorant analysis? Within a couple of weeks we will likely have a much clearer account of what happened and–to the extent that it is possible–why. If you can’t wait that long to learn the facts, then you may want to examine your own motives. Is it concern for the victims and for possible future victims? Or is it just tragedy voyeurism (using the horrific details of tragedy just to titillate) or outrage porn (turning tragedy into fuel for your pre-existing political self-righteousness)?

Stop rewarding murderers. Start rewarding courage.

Martin Shkreli, hedge fund manager and founder of Turing Pharmaceuticals, has been

Martin Shkreli, hedge fund manager and founder of Turing Pharmaceuticals, has been