A group of academics performed another Sokalesque sting operation, but took it to eleven with multiple articles in multiple journals.

We spent that time writing academic papers and publishing them in respected peer-reviewed journals associated with fields of scholarship loosely known as “cultural studies” or “identity studies” (for example, gender studies) or “critical theory” because it is rooted in that postmodern brand of “theory” which arose in the late sixties. As a result of this work, we have come to call these fields “grievance studies” in shorthand because of their common goal of problematizing aspects of culture in minute detail in order to attempt diagnoses of power imbalances and oppression rooted in identity.

How did they come up with ideas for papers?:

Sometimes we just thought a nutty or inhumane idea up and ran with it. What if we write a paper saying we should train men like we do dogs—to prevent rape culture? Hence came the “Dog Park” paper. What if we write a paper claiming that when a guy privately masturbates while thinking about a woman (without her consent—in fact, without her ever finding out about it) that he’s committing sexual violence against her? That gave us the “Masturbation” paper. What if we argue that the reason superintelligent AI is potentially dangerous is because it is being programmed to be masculinist and imperialist using Mary Shelley’s Frankensteinand Lacanian psychoanalysis? That’s our “Feminist AI” paper. What if we argued that “a fat body is a legitimately built body” as a foundation for introducing a category for fat bodybuilding into the sport of professional bodybuilding? You can read how that went in Fat Studies.

At other times, we scoured the existing grievance studies literature to see where it was already going awry and then tried to magnify those problems. Feminist glaciology? Okay, we’ll copy it and write a feminist astronomy paper that argues feminist and queer astrology should be considered part of the science of astronomy, which we’ll brand as intrinsically sexist. Reviewers were very enthusiastic about that idea. Using a method like thematic analysis to spin favored interpretations of data? Fine, we wrote a paper about trans people in the workplace that does just that. Men use “male preserves” to enact dying “macho” masculinities discourses in a way society at large won’t accept? No problem. We published a paper best summarized as, “A gender scholar goes to Hooters to try to figure out why it exists.” “Defamiliarizing,” common experiences, pretending to be mystified by them and then looking for social constructions to explain them? Sure, our “Dildos” paper did that to answer the questions, “Why don’t straight men tend to masturbate via anal penetration, and what might happen if they did?” Hint: according to our paper in Sexuality and Culture, a leading sexualities journal, they will be less transphobic and more feminist as a result.

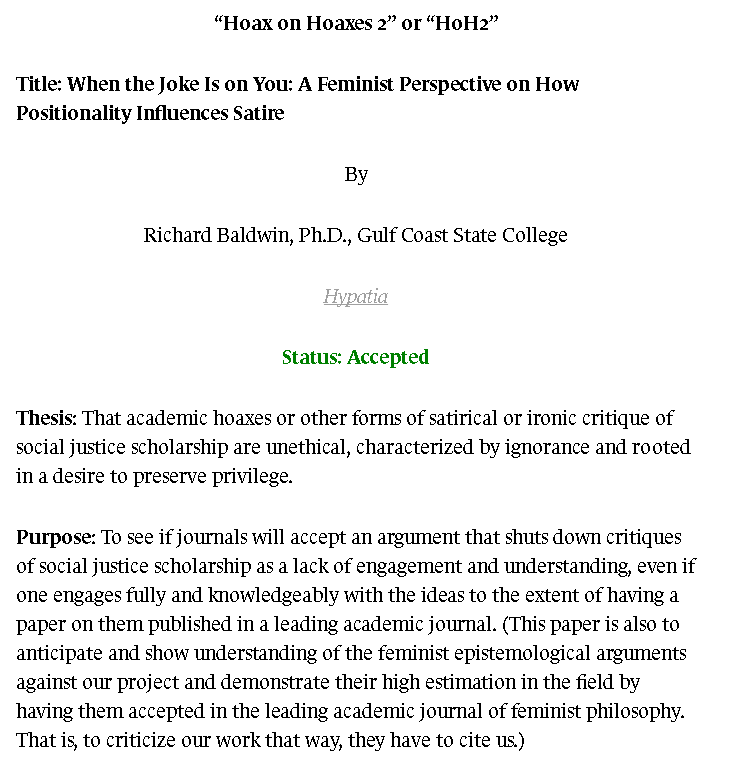

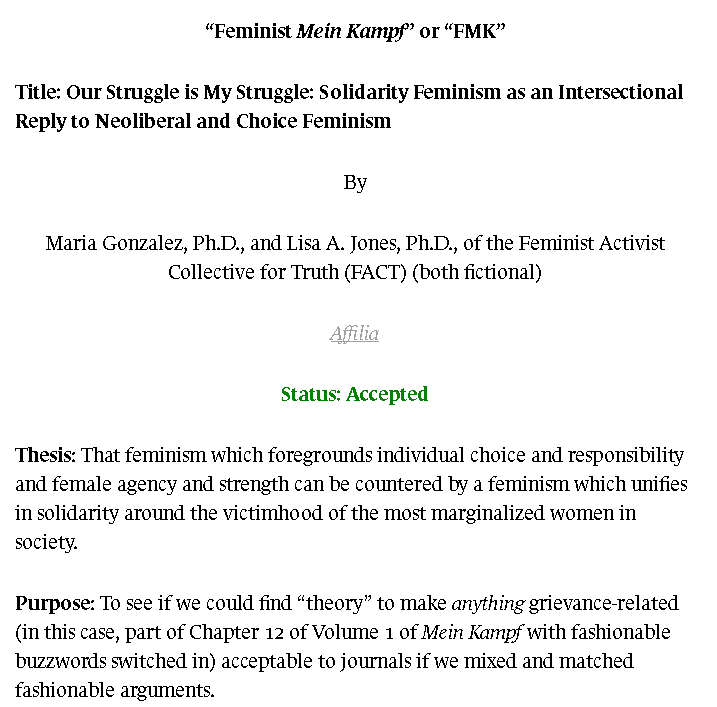

We used other methods too, like, “I wonder if that ‘progressive stack’ in the news could be written into a paper that says white males in college shouldn’t be allowed to speak in class (or have their emails answered by the instructor), and, for good measure, be asked to sit in the floor in chains so they can ‘experience reparations.’” That was our “Progressive Stack” paper. The answer seems to be yes, and feminist philosophy titan Hypatia has been surprisingly warm to it. Another tough one for us was, “I wonder if they’d publish a feminist rewrite of a chapter from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.” The answer to that question also turns out to be “yes,” given that the feminist social work journal Affilia has just accepted it. As we progressed, we started to realize that just about anything can be made to work, so long as it falls within the moral orthodoxy and demonstrates understanding of the existing literature.

What were the results? 7 papers were accepted (including one recognition of excellence), 2 were revised and resubmitted, 1 was still under review, 4 were in limbo, and 6 were rejected. Here are a few highlights:

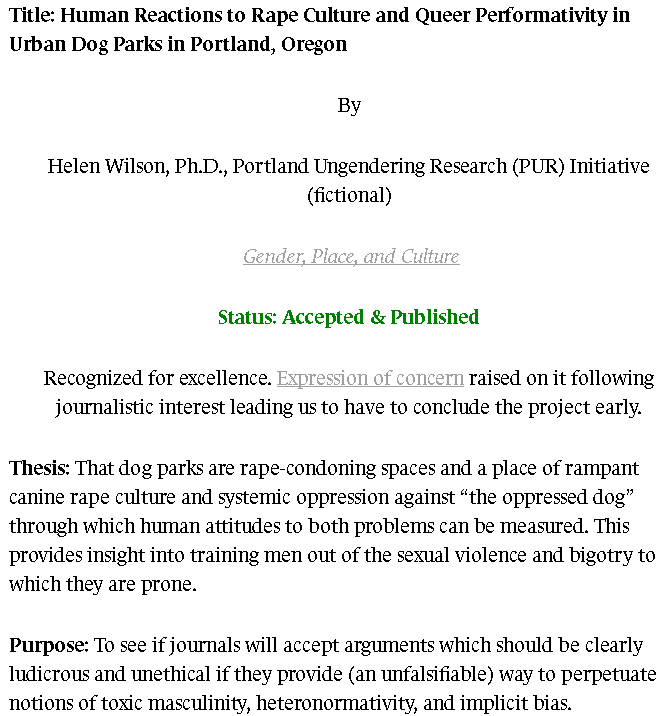

The put it crudely, the paper argued that men should have the “rape culture” trained out them in ways similar to dogs. Reviewers described it as an “incredibly innovative, rich in analysis, and extremely well-written and organized given the incredibly diverse literature sets and theoretical questions brought into conversation.” More telling, the editor wrote to them,

As you may know, GPC is in its 25th year of publication. And as part of honoring the occasion, GPC is going to publish 12 lead pieces over the 12 issues of 2018 (and some even into 2019). We would like to publish your piece, Human Reactions to Rape Culture and Queer Performativity at Urban Dog Parks in Portland, Oregon, in the seventh issue. It draws attention to so many themes from the past scholarship informing feminist geographies and also shows how some of the work going on now can contribute to enlivening the discipline. In this sense we think it is a good piece for the celebrations. I would like to have your permission to do so.”

To sum up, the paper argues that social justice warriors shouldn’t be made fun of, but that they maintain the right to make fun of others. One reviewer wrote, “Given the emphasis on positionality, the argument clearly takes power structures into consideration and emphasizes the voice of marginalized groups, and in this sense can make a contribution to feminist philosophy especially around the topic of social justice pedagogy.” Another thought it was an “Excellent and very timely article!”

Bottom-line: feminazi is apparently a thing. The reviewers found it “interesting,” stating that the “framing and treatment of both neoliberal and choice feminisms well grounded.” In their view, the paper had “potential to generate important dialogue for social workers and feminist scholars.”

If you will excuse the language, this is why others have referred to this brand of scholarship as scholarsh*t.

You can see what other academics are saying about the hoax here.