The National Academy of Sciences released a comprehensive report earlier this year that “builds on previous related Academies reports published between 1987 and 2010 by undertaking a retrospective examination of the purported positive and adverse effects of GE crops and to anticipate what emerging genetic-engineering technologies hold for the future.” Here are the highlights from the press release:

- Effects on human health: “The committee carefully searched all available research studies for persuasive evidence of adverse health effects directly attributable to consumption of foods derived from GE crops but found none. Studies with animals and research on the chemical composition of GE foods currently on the market reveal no differences that would implicate a higher risk to human health and safety than from eating their non-GE counterparts. Though long-term epidemiological studies have not directly addressed GE food consumption, available epidemiological data do not show associations between any disease or chronic conditions and the consumption of GE foods. There is some evidence that GE insect-resistant crops have had benefits to human health by reducing insecticide poisonings. In addition, several GE crops are in development that are designed to benefit human health, such as rice with increased beta-carotene content to help prevent blindness and death caused by vitamin A deficiencies in some developing nations.”

- Effects on the environment: “The use of insect-resistant or herbicide-resistant crops did not reduce the overall diversity of plant and insect life on farms, and sometimes insect-resistant crops resulted in increased insect diversity, the report says. While gene flow – the transfer of genes from a GE crop to a wild relative species – has occurred, no examples have demonstrated an adverse environmental effect from this transfer. Overall, the committee found no conclusive evidence of cause-and-effect relationships between GE crops and environmental problems. However, the complex nature of assessing long-term environmental changes often made it difficult to reach definitive conclusions.”

- Effects on agriculture: “The available evidence indicates that GE soybean, cotton, and maize have generally had favorable economic outcomes for producers who have adopted these crops, but outcomes have varied depending on pest abundance, farming practices, and agricultural infrastructure. Although GE crops have provided economic benefits to many small-scale farmers in the early years of adoption, enduring and widespread gains will depend on such farmers receiving institutional support, such as access to credit, affordable inputs such as fertilizer, extension services, and access to profitable local and global markets for the crops. Evidence shows that in locations where insect-resistant crops were planted but resistance-management strategies were not followed, damaging levels of resistance evolved in some target insects. If GE crops are to be used sustainably, regulations and incentives are needed so that more integrated and sustainable pest-management approaches become economically feasible. The committee also found that in many locations some weeds had evolved resistance to glyphosate, the herbicide to which most GE crops were engineered to be resistant. Resistance evolution in weeds could be delayed by the use of integrated weed-management approaches, says the report, which also recommends further research to determine better approaches for weed resistance management. Insect-resistant GE crops have decreased crop loss due to plant pests. However, the committee examined data on overall rates of increase in yields of soybean, cotton, and maize in the U.S. for the decades preceding introduction of GE crops and after their introduction, and there was no evidence that GE crops had changed the rate of increase in yields.[ref]I’m surprised by this finding considering there are numerous studies that find GMOs increase crop yields.[/ref] It is feasible that emerging genetic-engineering technologies will speed the rate of increase in yield, but this is not certain, so the committee recommended funding of diverse approaches for increasing and stabilizing crop yield.”

Add this to the statements by the World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science that GMOs are safe. Concerns over increased chemical use may be somewhat legitimate, though this tends to be complicated. However, fears about herbicides like glyphosate are often overblown, seeing that both the EPA and the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization and WHO declare that it is not a cancer risk. Furthermore, it is important to note that uncontrolled weeds are actually a potentially huge threat, making weedkillers all the more important. As for increased herbicide resistance, science writer Ronald Bailey explains in his book The End of Doom: Environmental Renewal in the Twenty-First Century,

What about “superweeds”? Again, the evolution of resistance by weeds to herbicides is nothing new and is certainly not a problem specifically related to genetically enhanced crops. As of April 2014, the International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds reports that there are currently 429 uniquely evolved cases of herbicide resistant weeds globally involving 234 different species. Weeds have evolved resistance to 22 of the 25 known herbicide sites of action and to 154 different herbicides. Herbicide resistant weeds have been reported in 81 crops in sixty-five countries. A preliminary analysis by University of Wyoming weed scientist Andrew Kniss parses the data on herbicide resistance from 1986 to 2012. He finds no increase in the rate at which weeds become resistant to herbicides after biotech crops were introduced in 1996. Since Roundup (glyphosate) is the most popular herbicide used with biotech crops, have the number of weed species resistant to Roundup increased? Kniss finds that the development of Roundup resistant weeds has occurred more frequently among non biotech crops. Glyphosate resistant weeds evolved due to glyphosate use, not directly due to GM crops,” he points out. “Herbicide resistant weed development is not a GMO problem, it is a herbicide problem (pgs. 155-156).

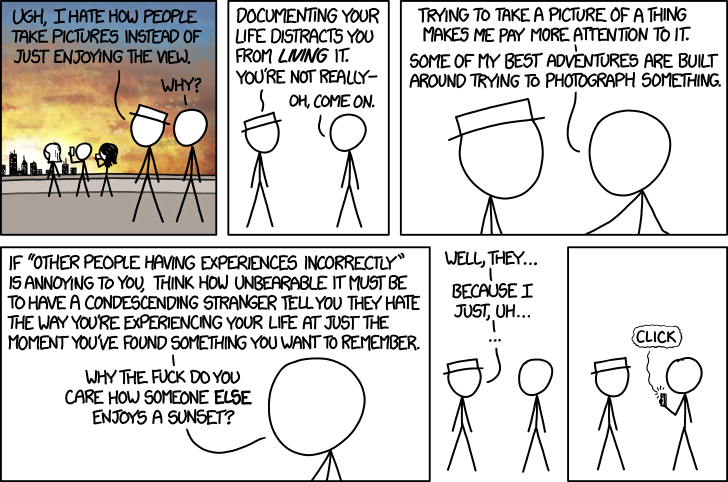

In summary, GMOs are indeed safe with relatively minor concerns. Or, as Slate‘s William Saletan puts it,

The more you learn about herbicide resistance, the more you come to understand how complicated the truth about GMOs is. First you discover that they aren’t evil. Then you learn that they aren’t perfectly innocent. Then you realize that nothing is perfectly innocent. Pesticide vs. pesticide, technology vs. technology, risk vs. risk—it’s all relative. The best you can do is measure each practice against the alternatives. The least you can do is look past a three-letter label.

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been

Calestous Juma, Professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, has a

Calestous Juma, Professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, has a