From Art Carden over at Forbes:

A new paper forthcoming in the journal American Economic Review: Insights estimates the effect of trade with China on American consumers and shows us what we stand to lose if we don’t end the trade war.

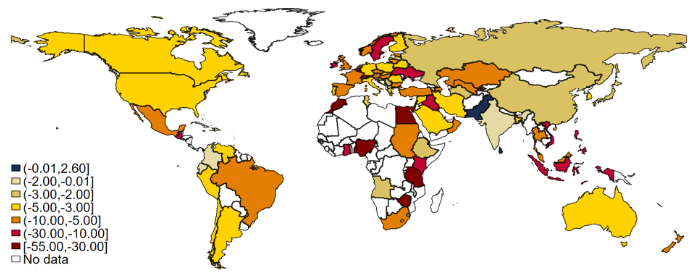

In “Estimating US Consumer Gains from Chinese Imports,” economists Liang Bai of the University of Edinburgh and Sebastian Stumpner of the University of Montreal and the Bank of France study price data from the Nielsen Homescan panel to find that trade with China reduced the prices Americans paid for consumer tradables by 0.19 percentage points per year. You can download a draft of the paper here.

Bai and Stumpner argue that about a third of the consumers’ gain from trade with China comes from greater product variety while the other two-thirds come from lower prices for the goods people were already buying.

Another way to put it is that inflation was lower–prices didn’t rise as rapidly–because of trade with China…The direction of the result won’t surprise economists, who have argued for centuries that international trade helps a country’s citizens by making it possible for them to get more with every hour of their hard-earned labor.

Scott Lincicome of the Cato Institute weighs in as well:

Trade and globalization have provided undeniable economic benefits for the vast majority of American families, businesses, and workers. Most obvious are the consumer gains. Several recent studies have found that freer trade with China, for example, has generated, through increased competition and lower prices, hundreds of billions of dollars in U.S. consumer benefits — benefits that, according to economists Xavier Jaravel and Erick Sager, are the equivalent of giving every American “$260 of extra spending per year for the rest of their lives.”[ref]I actually think he might be citing this instead.[/ref] Consumer gains from imports, in general tilted toward the poor and the middle class, are especially tilted toward them when it comes to goods that are made in China and sold at stores like Walmart. The magnitude of such benefits also debunks the well-worn myth that free trade is mainly about cheap T-shirts. Indeed, trade’s consumer surplus is a big reason that Americans today work far fewer hours to own far better essentials than at any prior time in U.S. history.

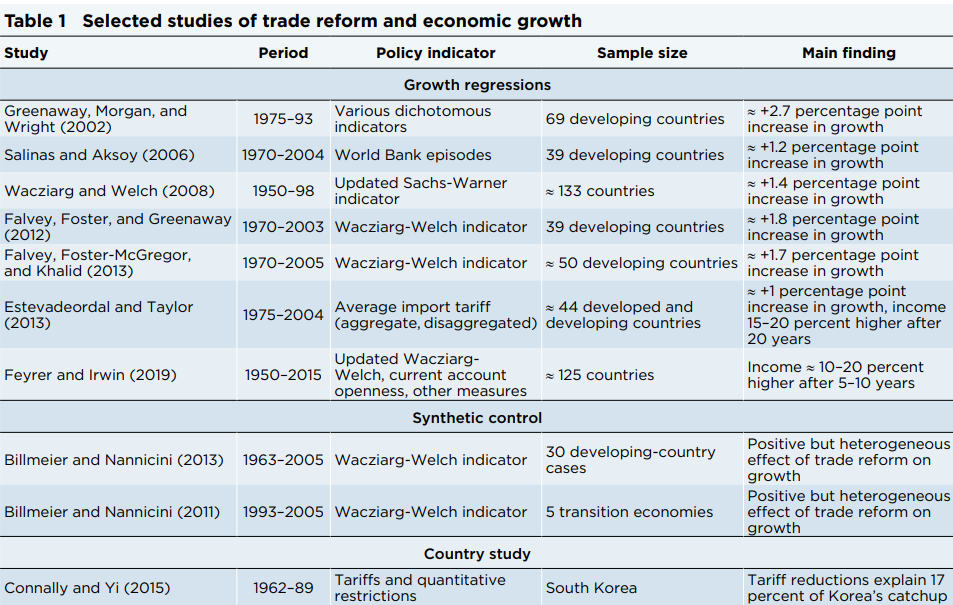

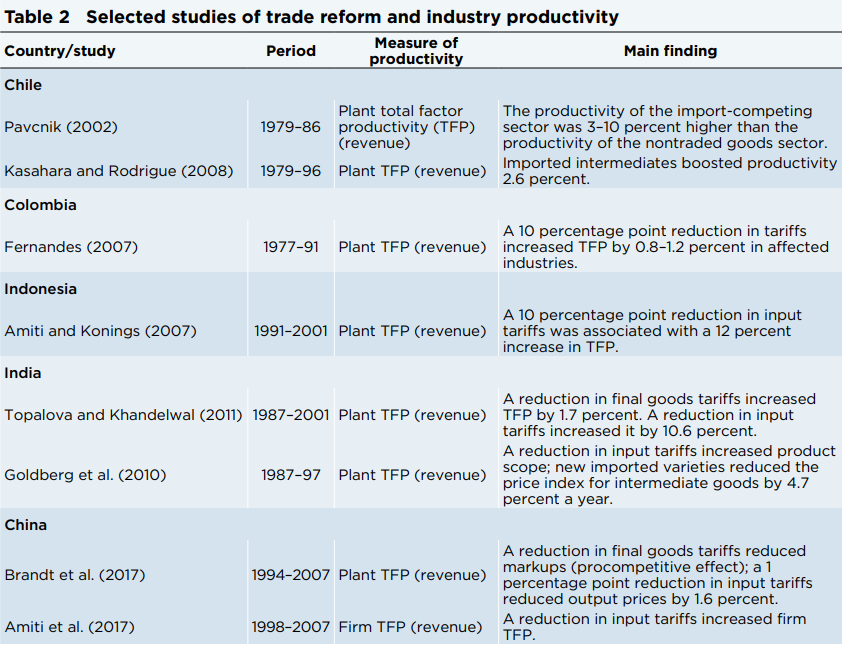

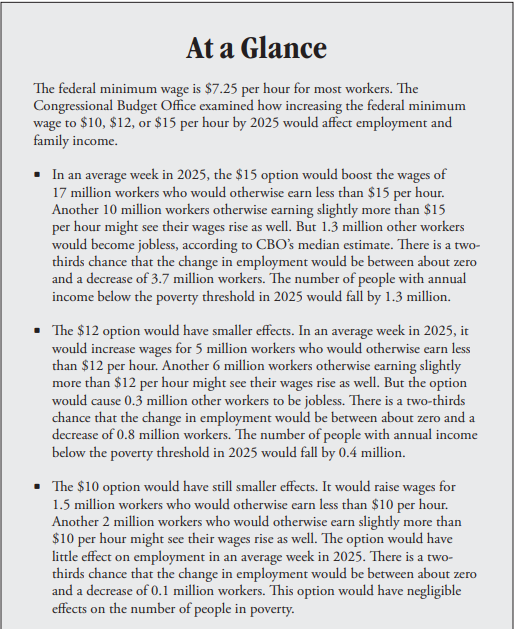

Then there are trade’s overall benefits for the economy. A 2017 Peterson Institute paper calculated the payoff to the United States from expanded trade between 1950 and 2016 to be $2.1 trillion, increasing U.S. GDP per capita and per household by around $7,000 and $18,000 — with benefits, again, disproportionately accruing to households in the bottom income decile. The U.S. International Trade Commission, moreover, found in 2016 that U.S. bilateral and regional trade agreements such as NAFTA generated small but significant annual increases in GDP, as well as in employment and real wages among highly skilled and less skilled American workers. As the American Enterprise Institute’s Michael Strain has noted, trade-skeptical populists who downplay this impressive macroeconomic boost ignore that, as our current economic moment attests, a small bit of extra GDP growth can mean big things for lower-wage, lower-skill workers in terms of employment and possible government assistance.

Trade and globalization also support American companies and workers, even in manufacturing. The Commerce Department, for example, has estimated that almost 11 million jobs depended on exports of U.S. goods and services in 2016, and foreign direct investment in the United States — the necessary flip side of our oft-maligned trade deficit — supported millions more. Meanwhile, American companies that adapt and thrive in today’s economy most often do so by making use of imports and global supply chains. The San Francisco Fed, for instance, recently estimated that almost half of U.S. imports are intermediate products purchased by American manufacturers to make globally competitive finished goods; the country’s biggest exporters, therefore, are also its biggest importers. Numerous other studies have found that the vast majority of the value of an American company’s assembled-abroad product (such as an iPhone, assembled in China) accrues to the U.S. company, including its workers and shareholders — not to the place of final assembly (despite what a gross bilateral trade balance, which attributes an import’s full cost to its final export source, might say).

…My 2017 survey of the academic literature on over a century of U.S. protectionism pre-Trump showed that, with very few exceptions, it imposed immense economic costs on American consumers, workers, and companies (more than $600,000 per year for every U.S. job created) while also failing to open foreign markets or resuscitate protected American firms and workers over the longer term. In case after case, the jobs still disappeared, and the companies either went bankrupt or came back to the government for more help. And it’s happening again: Though American steel consumers are paying much higher prices than their global competitors, U.S. steel-industry stocks lag far behind the S&P 500 index. For these and related reasons, economists of the Left, Right, and center continue to oppose tariffs overwhelmingly (93 percent of a recent IGM Economic Experts Panel of dozens of top economists, to be exact), and they support freer trade and globalization.

Say again: free trade is good.