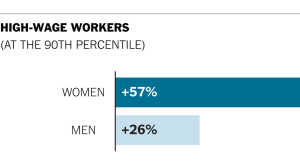

The Harvard Business Review has an article that is at once shocking and utterly obvious. The premise of the article is that in a lot of demanding (and also very lucrative) professional service careers there is a culture that demands ridiculous hours as a signal that an employee is fully committed to the team. “We often think of problems with these expectations as women’s problems,” says Erin Reid, “But men too may struggle with them.”

Reid found that there were a couple of important differences, however. The biggest is that men have two choices when they refuse to sell their souls to the job: they can either publicly ask for more accommodation or they can “pass” which is to say: lie about how much they work. If they take the path of formally asking for less-demanding positions (e.g. asking for a domestic rather than an international assignment, asking for time off after a child is born), then they face the same stiff penalties as women who ask for official accommodation: lost promotions and marginalization. But if they can successfully hide their true hours and get away with working less than people assume they do, then they can simultaneously work fewer hours and preserve their sterling reputations.

I haven’t ever worked in a management consulting firm or similar high-pressure environment. My corporate experience has been like a watered-down version of these trends, but it’s the same basic concept.[ref]My current position is with a small company, so it’s very different than corporate culture of any kind.[/ref]Conspicuous overwork is like conspicuous consumption: a way to signal that you’re part of the in-group. I’ve always been disgusted by the dishonesty that goes along with it, however. No one ever (in my experience) lied outright about their hours, but based on observations and conversations I’m sure that a lot of white-collar professionals vastly overstate their hours to their bosses and often to themselves. Not when they actually have to record their hours, but when they are paid salary and the hours are implied.

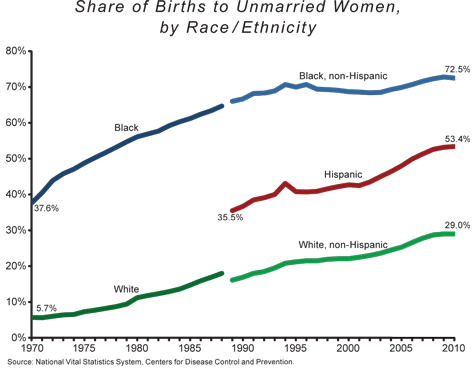

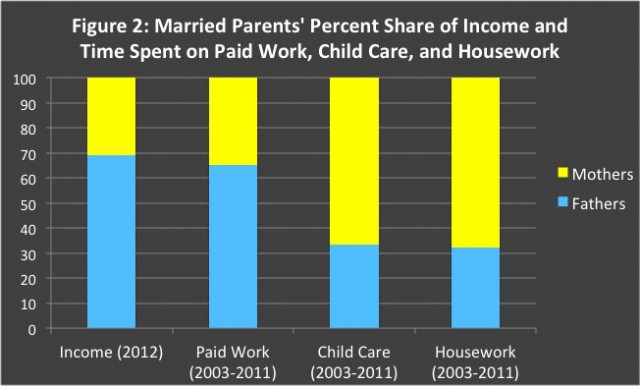

Another thing to note: the bias was specifically anti-family.

Intriguingly, the pushback men received for asking for time away from work seemed limited to time for family: one man who had since left the firm told me that, when his daughter was born he had been harassed for taking two weeks of paternity leave, despite spending some of that leave working. But when, later that year, he and his family took a three-week vacation to an exotic locale, the vacation was permitted, and his team encouraged him to “unplug” and take a real vacation. This disparity in treatment seems, at one level, ridiculous, but at another level, entirely consistent with the firm’s expectation that men be ideal workers: taking on mundane responsibilities in one’s family life can threaten one’s devotion to work, while affording an expensive vacation may be instead contingent upon devotion to and success at work.

I believe the problem starts with outmoded vestiges of Industrial Revolution assumptions. During that time–when professional work in large corporations first became widespread–a lot of the work was mechanized. In that scenario your productivity as a worker is basically equivalent to the time you spend pulling the lever (or whatever it is you’re supposed to do.) Partially this outdated assumption is sticking with us based on sheer inertia, but I think the bigger explanation has to do with the big differences between client-facing roles and knowledge roles. There are lots of coders, data analysts, and other knowledge workers who would get much more done with 12 hours of hard work per week (and some overhead for meetings and maintenance) than 50 hours spent primarily browsing Facebook and pretending to work. But if you give them genuine freedom to work as effectively as possible, you will likely enrage the client reps who really do need to be at their desk (or otherwise available) throughout the entire work day no matter what.

It gets trickier when you consider that the knowledge workers are generally highly-skilled and probably better paid, while client-facing folks (like call center employees, to use an extreme example) are much closer to entry level. I’m not sure that I want a super-efficient system if it means creating such a major divide between self-directed knowledge workers with tremendous freedom and lower-level employees who are locked in to 9-5 drudgery.

In the long run, you hope that all the boring jobs eventually get taken over by computers and we all become highly-skilled, self-directed workers, but transitioning to that point without great injustice (not to mention civil unrest) is a tricky, tricky problem. In the meantime, however, it would great for companies to drop the unrealistic expectations of hyper-schedules and realize that, in the long run, fathers and mothers are both better workers when are treated more like humans and less like resources. The potential to have more fairness for male and female workers and a healthier society in general (as family takes greater priority) is a win-win.

cent piece from

cent piece from