A couple of weeks ago I wrote a frustrated counter-reaction to criticisms of Elder Callister’s article “What is the Lord’s Standard for Morality?” A lot of folks liked it. A lot of other folks did not. I found friends and family in both camps. That made me cautious as I wrote this followup. Not because I temper my words to try and please people, but because when folks I respect disagree with me I like to take the time to listen and reconsider. So I listened. And I reconsidered. This post is the result.

A Rock and a Hard Place

The idea that we should be careful in how we talk about sexual morality is valid. Last year, Elizabeth Smart provided a stark example. She described how an object lesson she’d heard in church that compared sex to chewing gum came to her mind after she was first raped by her kidnapper.

I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’m that chewed up piece of gum, nobody re-chews a piece of gum, you throw it away.’ And that’s how easy it is to feel like you know longer have worth, you know longer have value. ‘Why would it even be worth screaming out? Why would it even make a difference if you are rescued? Your life still has no value.’

I’m sure that the person who gave this lesson meant well, but that object lesson (along with its cousins: the nail in the board, the licked cupcake, and the crumpled rose) is an example of purity culture, and purity culture is Satanic. Most of the time when we talk about sin, we use a mistake-paradigm. Sins are mistakes, and through the Atonement they can be fixed. Jesus says “though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.”[ref]Isaiah 1:18[/ref] It is true that the Atonement cannot erase the consequences of our sins, but it can and does make us whole. That’s the point, and for the most part, it’s what we teach.

I’m sure that the person who gave this lesson meant well, but that object lesson (along with its cousins: the nail in the board, the licked cupcake, and the crumpled rose) is an example of purity culture, and purity culture is Satanic. Most of the time when we talk about sin, we use a mistake-paradigm. Sins are mistakes, and through the Atonement they can be fixed. Jesus says “though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.”[ref]Isaiah 1:18[/ref] It is true that the Atonement cannot erase the consequences of our sins, but it can and does make us whole. That’s the point, and for the most part, it’s what we teach.

Except when it comes to sexual sins. Then, suddenly, we switch from a mistakes-paradigm to a purity-paradigm. You can fix something that is broken, but rotten meat is bad forever. Even more pernicious, however, purity-culture makes it seem as though virginity and chastity are the same thing. This implies that even a victim of a rape should somehow bear the guilt of sexual transgression. That is an abominable and indefensible teaching. The mistakes-paradigm is compatible with Christianity. Purity culture, although it’s often preached by Christians, is not. It is antithetical to the Savior’s message of hope and redemption. It is what Satan, the accuser, wants us to believe.

As she recounts in her autobiography, Smart remembered that lesson when it could have done the most harm to her. She was rescued from despair, however, by the memory of love. She knew that her mother and father would accept her back with loving and open arms no matter what had been done to her. Throughout her awful ordeal, she remembered the love of her family and felt the love of her Heavenly Father. Love won out, and because of that Elizabeth found the resolve to endure and, in the end, to defeat her tormentors. But first she had to defeat a false teaching she had been subjected to in Sunday school.

There is more to the story. As I wrote at the time, headlines covering her comments ran along the lines of “Elizabeth Smart: Abstinence-only education can make rape survivors feel ‘dirty,’ ‘filthy’” and “Traditional Mormon Sexual Purity Lesson Contributed to Captivity, Elizabeth Smart Tells University Audience.” There was no shortage of those who were ready to use her words to score points for the world’s view of sexual freedom, whether she agreed or not.

The Church’s unwavering adherence to strict moral standards is unusual in our modern society, and it is under constant attack. This attack could have tragic consequences, precisely because the Church’s stark and plain teachings on chastity and morality have measurable, beneficial effects. A 4-year study conducted at the University of North Carolina found that, compared to other religious denominations, Mormon youths were more devout, more able to articulate their own faith, and more likely to adhere to the standards set by the Church. As Deseret News reported, the study found that fewer Mormon teens:

- Engaged in sexual intercourse

- Had ever smoked pot

- Drank alcohol a few times a year

- Watched x-rated or pornographic programs in the past year

There’s good reason to believe that clear teachings contribute to these measurably different outcomes for Mormons. Researcher Stephen Vaisey interviewed more than 20 Mormon youths for the project, and subsequently noted:

One of the groups that stood out … were the Mormons. In general they tended to be more articulate about their religion, what their religion actually taught and what kind of religious constraints it placed on them. [emphasis added]

Plain and unflinching talk from Church leaders is a shield between our children and the dangerous temptations of our modern world. These teachings are not a matter of sheltering youth, but rather of empowering them to see clearly the choices that lie before them.

We are trapped between the rock of purity culture and the hard place of the world’s dismissal of the seriousness of sexual sin.

Daggers Placed to Pierce Their Souls

The response to my original post that surprised me the most was the oft-repeated complaint that I had skipped over the worst line in the talk. That was:

In the end, most women get the type of man they dress for.

Some folks accused me of leaving it out because I didn’t know how to account for it, but the truth is that I left it out because it didn’t even register as problematic. I took it to be just a simple observation that dress, along with many other factors, is one way that like-minded individuals identify potential mates in a process known in economics, sociology and anthropology as assortative mating. If you would like to marry a man who values modesty in dress, then it makes sense to dress modestly. (The existence of assortative mating is itself so well known that some studies fault it for rising income inequality.)

Others, however, pointed out that the word “get” as opposed to “marry” was just too similar to the phrase “get what they deserve” and that, combined with a reference to a woman’s dress, it was just too close to victim-blaming. I do not dispute the validity of this reaction. One of the things I’ve learned, especially in private discussions, is that people can react to the same words in very, very different ways and that if you are willing to listen you will generally learn that people have good reasons for reacting the way that they do.

More than anything else, these discussions reminded me of Jacob’s haunting and cutting words when he spoke about chastity:

7 And also it grieveth me that I must use so much boldness of speech concerning you, before your wives and your children, many of whose feelings are exceedingly tender and chaste and delicate before God, which thing is pleasing unto God;

8 And it supposeth me that they have come up hither to hear the pleasing word of God, yea, the word which healeth the wounded soul.

9 Wherefore, it burdeneth my soul that I should be constrained, because of the strict commandment which I have received from God, to admonish you according to your crimes, to enlarge the wounds of those who are already wounded, instead of consoling and healing their wounds; and those who have not been wounded, instead of feasting upon the pleasing word of God have daggers placed to pierce their souls and wound their delicate minds.

10 But, notwithstanding the greatness of the task, I must do according to the strict commands of God, and tell you concerning your wickedness and abominations, in the presence of the pure in heart, and the broken heart, and under the glance of the piercing eye of the Almighty God.[ref]Jacob 2:7-10[/ref]

I always imagined, when I read these verses as a kid, that the women and children in the crowd must have just had very delicate Victorian sensibilities about the topic of sex. Now I realize how dubious that reading is, and I wonder how many of those in the audience had been traumatized by sexual assault, rape, and abuse. I don’t say this to give Elder Callister a get-out-of-jail-free card, because after all the big difference between Jacob’s words and the Ensign article is that Jacob gave this extended apology/warning (the earliest known trigger warning?) and Elder Callister did not.

My position is this: I think Elder Callister meant no ill will, and that it’s probably impossible to talk about these issues without causing pain to at least some people. As an audience, we should try to understand the principle behind the words. But I also would hope that our leaders can continue to learn how to be as careful as they may, without diluting the message, in picking their words, and I sincerely acknowledge the validity of those who were hurt by these words. Perhaps it is some comfort, in re-reading Jacob 2, to find yourself in good company.

What is Rape Culture, Anyway?

A post at Feminist Mormon Housewives called me out for misunderstanding what the term “rape culture” means. To be fair: that’s valid. I have my own definition of rape culture, but I shouldn’t have used a non-standard definition without more carefully explaining what it was and that it’s non-standard. I’m not going to get into that now, either (although the basics are in my original post). Instead, let’s just pause and consider a small irony.

One of the primary concerns with Elder Callister’s talk is that he used words and phrases that could be hurtful to his audience, even if the hurtful meaning wasn’t intended or even logically implied by his words. And that is valid. But wouldn’t the same concern apply to deploying a deliberately inflammatory term like “rape culture” to describe the talk? After all, there are quite a few people who aren’t familiar with the technical definition (that’s not in dispute, since the FMH post takes the trouble of providing the definition) so, by their own logic, perhaps critics ought to be more careful with their language? Just to be clear, my concern is not that Elder Callister’s feelings might be hurt, but rather that a very large number of faithful Mormons who do not keep current on feminist political terminology will be confused and hurt when some of their fellow Mormons start associating a general authority and advocacy of rape. So really, by the logic of the critics of the talk, we shouldn’t even be having a conversation using the term “rape culture” at all.

The substance of the rape culture accusation could be made without the incendiary terminology. Using the conventional definition, rape culture is the idea that common attitudes can lead indirectly to rape. Specific examples of rape culture include anything that condones or advocates (1) victim-blaming, (2) sexual objectification, or (3) trivializing rape. I don’t think anyone is seriously arguing that the talk trivializes rape. We’ve already talked about how the “get the type of man they dress for” line sounded like victim blaming. I have already conceded the validity of that painful association, but I am not willing to go from sounds like victim-blaming to engages in victim-blaming. (The observation that women’s dress can affect men doesn’t rise to the level of victim-blaming, either.)

So that leaves sexual objectifcation. Here the problem is not with any particular phrasing of any particular talk, but with the concept of modesty as it exists in Mormonism. Critics argue that emphasizing modest dress turns women into sexual objects, and that the only solution is to talk about modesty less. (They also argue that we should encourage women to dress modestly for themselves and not just for the sake of men, but I’m not going to go into that because I agree with it.) So, should the Church shut up about modesty, or at least talk about it a little bit less?

Will the Real Moderates Please Stand Up

As I mentioned, the number one criticism of my post was that I had skipped over the “get the type of man they dress for” line. Only slightly less prominent, however, was the argument that the critics of Elder Callister’s talk didn’t have anything against the Church’s standards or teachings on modesty. The theory was that the big kerfuffle wasn’t about what Elder Callister said. It was just about how he said it. I don’t for a moment doubt that the folks who told me that were sincere, but it’s worth pointing a couple of things out. First, even though some of them said (effectively) “I’m not going to criticize the content, just the delivery” they also disagreed with the content. Their position was “I think Elder Callister is wrong about sexual morality, but I’m choosing only to criticize his delivery. Not his message.” In other words, lots of the critics do, indeed have a beef with the Church’s positions. Secondly, plenty of the folks criticizing the talk did quite plainly criticize the Church’s teachings as well.

The original piece that set me off (Natasha Helfer Parker’s Morality? We can do much better than this) included an explicit rejection of the Church’s teaching that homosexuals ought to remain chaste and urged a shift to accepting monogamous gay sexual relations as moral. Several of the commenters on my piece insisted that, since there’s no direct scriptural evidence against masturbation, it ought not to be considered a sin (or at least, not a serious one). I was tempted to write this off as one of those weird, fringe issues that make the Internet such an interesting place until another piece at Feminist Mormon Housewives made the exact same case:

If you are going to say that the Lord condemns masturbation, please cite me chapter and verse on that. Masturbation is something that a vast, VAST majority of people on the earth and in the church have done. If it is sinful, it is a sin like lying, being inconsiderate, or any number of other mistakes that we all deal with.

And of course, in addition to teachings on homosexuality and masturbation, there are also those who would call for the Church to stop speaking so loudly and clearly about modesty. So, to my friends who tried to tell me that I was getting upset at nothing because no one actually challenged the Church’s teachings, I have to say: “look again.”

Keep in mind that in the first section of this post I argued (1) that the Church’s uniquely clear teachings on moral issues had led to uniquely positive results for our youth and (2) that the world outside is ready to abuse any possible opening to attack those teachings. In that context, the important thing isn’t that certain members of the Church feel comfortable publicly calling for the Church to retreat from traditional teachings. Instead, the important thing is why. What is the rationale behind this call for the Church to moderate moral teachings?

Sara Katherine Staheli Hanks’ (who wrote the FMH piece quoted above) argument boils down to the ever-classic: But everyone’s doing it! (Her exact words, just to re-quote, were that “Masturbation is something that a vast, VAST majority of people on the earth and in the church have done.” So, how bad can it be, right?) Parker, on the other hand, wrote that the standard on homosexual sex should be lowered because it “sets the Mormon LGBTQ population up for almost guaranteed failure,” and then broadened that logic at the end when she said: “The way that sexual standards are presented in this type of talk is unrealistic and sets people up for failure.”

It’s impossible to tell exactly which standards, other than those concerning homosexuality, Parker believes the Church should revise downwards, but the logic is basically limitless. If we accept the idea that whenever the Church’s standards get too high we need to lower them to more realistic levels, then they aren’t really standards at all. They are more like best practices or conventions. The principle of idealism cannot survive that assault. As I stated in my original piece: this logic is fundamentally anti-Christian. It’s the counterpart to purity culture. Purity culture says the Atonement cannot save you, and lowering standards until people can achieve them on their own says the Atonement is not needed to save you. These are just two different ways to repudiate the Gospel.

As much as moderate critics of Elder Callister’s talk may earnestly and sincerely believe in simply improving the way that we talk about sexual morality, it’s important to realize that we’re having that conversation in the midst of a greater battle. There are people both inside and outside the Church who are more than happy to use sincere complaints about how the Church teaches what it teaches to fuel their complaints about what the Church teaches. I don’t think that means that moderate critics ought to be silent or that their concerns are not legitimate. I just hope it explains the reaction of folks like me.

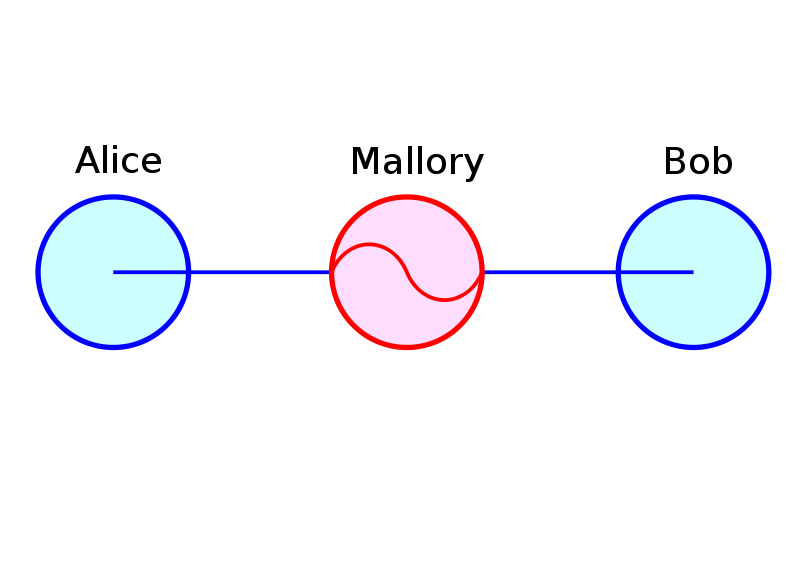

The Man-in-the-Middle Attack

This last section of my response is the most theoretical, but perhaps also the most important. It starts with a concept from cryptography. The man-in-the-middle attack is basically just what it sounds like: two people are trying to communicate to each other and a third party steps between them, intercepts the message, modifies it (possibly), and then sends it on. For example, if you’re logging on to your bank and a hacker is trying to intercept your communication to steal your password, then he’s trying to pull off the man-in-the-middle attack.

Let’s imagine someone trying to pull of a man-in-the-middle attack to sabotage communication between the general authorities (at one end) and the members of the Church (on the other end). A silly example would be to try and hack into the Church’s servers and modify the text of the Ensign so that what the GAs sent out and what the members received wasn’t the same. That’s a silly example because it would be so obvious (among other reasons). But what if, instead of hacking into the Church’s servers, an adversary were to metaphorically hack into the minds of members of the Church and change the way they perceived certain words and phrases? In that case, the words the General Authorities used would not mean the same thing to their audience that they meant to the General Authorities. More importantly, however, the sabotage would be a lot harder to detect because everyone would be so busy arguing about what the “right” meaning of the terms was. The argument over who to blame, the leaders or the members, would obscure the deeper reality: someone had driven a wedge between the watchmen on the walls and the people they are there to warn.

What might this look like in practice? The most obvious examples is the way that professional counselors (like Parker) took Elder Callister to task for using the word “abuse” (when he called masturbation “self-abuse”) in a non-technical sense. Not only did Parker do this, but Hanks followed suit: “Do not co-opt a clinical term used to describe things like ritualistic cutting or burning of the skin to describe masturbation.” This is a fundamental misunderstanding of the way language works. Every specialized discipline in the world finds the need to invent new jargon and repurpose existing words from everyday language, but these technical terms are derived from the ordinary words and they are only valid within specific contexts. To argue that someone in a non-specialist outlet ought to be subject to specialized use of a term is not only irrational, it’s impossible. This is because quite often the same word will get repurposed again and again by different specialties. Off the top of my head, the phrase “tipping point” has a perfectly understandable meaning in plain English, but it also has a more technical meaning in economics and another, different, technical meaning in catastrophe theory. There’s a reason that Wikipedia had to invent disambiguation pages.

This example is too obvious to be a really powerful man-in-the-middle attack. The whole point of Parker’s critique is to assert the dominance of her expertise by calling Elder Callister wrong. Later on, when it starts to become a matter of course that we should bow to expert terminology, it may start to function as a man-in-the-middle attack, but for now we’re looking for a more subtle example. For example: Is it possible that the reaction to the “get the type of man they dress for” line is exacerbated because adherents of rape culture are actively looking for suspicious phrases? In other words, if you really believe in a political philosophy dedicated to unmasking sinister meanings behind otherwise ordinary terms, you’re probably going to find them whether they exist or not. This is the same danger behind accusation of dog whistle politics. When you’re accusing someone of something that is by definition hidden, how can they defend themselves? The reality is that anyone dedicated enough and clever enough is going to be able to find evidence of rape culture just about anywhere with only a little bit of effort and creativity.

This may seem like an academic quibble about linguistics, but the reality is that arguments about language are almost always really arguments about principles in the end. Without questioning the validity or sincerity of those who were hurt by Elder Callister’s word choice, I simply want to raise the possibility that in figuring out who is to blame, we may want to consider those who actively encourage us to look for evil intentions behind every ordinary turn of phrase. To the extent that secular politics (from any end of the spectrum) start to change the way we perceive the words we hear, there’s a risk that we’re starting to lose contact with the General Authorities. We should probably make it a matter of conscious effort to set aside our political filters somewhat when listening to what they have to say.

Where is Eve!? What did Mallory do with her!? That’s what I want to know!

“We should probably make it a matter of conscious effort to set aside our political filters somewhat when listening to what they have to say.”

If I take this as the sum and substance of your re-reply, I agree. Full stop.

But (can’t help myself . . .) you do ask us to be mind-readers. What do I think he means? Which decade’s vocabulary is he using? Is this a new saying or a repeat? I hear a different phrasing, different choice of words (than last time)–does that mean something, or is it really just old wine in a new bottle?

The problem with the man-in-the-middle argument is that a man-in-the-middle attach requires subterfuge. If the sender or recipient or both know the message has been altered, the attack will fail. It doesn’t matter that change was made in secret. The very fact of a change, however it occurred, is enough to set aside the message and seek correction.

In the case of language, we know there has been a change. It may be that the change comes from a peculiar or idiosyncratic or political or mercantile point of view. It may even be that the change was made with malicious intent. We may disavow and (violently or peacefully) resist the change. But in the midst of our dismay, the reality is that meaning has changed, that common usage has morphed, AND WE KNOW IT.

So when I hear someone use words and phrases that have a new, morphed, altered, meaning, what am I to think? Did he mean what it sounds like (since surely the new usage is as obvious to him as to me)? Or did he mean what he said last time in different words? Or did he mean what someone listening in 1990 (or 1950 or 1830) would likely hear? Or something else?

I have an answer for myself, which I think is both charitable and “a conscious effort to set aside political filters”, which is to compare ages (speaker and me) and roll back in my mind to language, words and phrase that I heard and used at the time the speaker was about 30 years old. My roll-back-to-30 filter.

I’d like something more–some subtlety, some sophisticated use of language, some acknowledgement of special or clinical or dated usage–I’d like that and I ask for it, but I don’t really expect it. And so I read and listen with my manufactured roll-back-to-30 filter, never knowing if that’s right or good but thinking it’s the best I’ve got.

Of course, any attempt to read closely, to analyze or discuss, to do with the text what I’d do with a statute or a judicial opinion, is difficult-to-impossible after applying such a fuzzy filter.

Hi Nate,

as the author of the referrenced FMH post, let me respond to your thoughts on that matter.

First, I’m glad you wrote this follow-up. It’s great to see some of the thought processes we all go through, and the things that help us stretch, grow and change our minds in some ways.

Anyway, …rape culture, and the usage of the term. Quite frankly, I agree with you that if you do not want to potentially shut down communication, and drive away a lot of people who may just not understand what the term means, or why someone would use it in relation to an Ensign article, the term is probably not a good one to use.

It does sound very “loaded”, or at least bad, and …unpleasant. I can totally see how it may put people off. Which is a major part of why I wrote that post. Many people do not know what it means, and probably were confused by its usage. And I wanted to make clear how it all connected.

So, I think I can agree with you there. But I do not think using the term is the same as someone communicating something they did not intend. When we called the comments out for feeding into rape culture, that was exactly what we meant (even though I concede that many may have been unfamiliar with the term and therefore put off by misunderstanding). This is not the same though as someone not communicating his intentions clearly.

For example, I’m German. If I say something, and use the German word for…dunno, tree, someone may not understand what I’m saying. And rightly so. But it doesn’t mean that I did not communicate exactly what I wanted to say, or used the word “tree” incorrectly. It’s just that the other person couldn’t understand me, because they were not familiar with German.

Elder Callister said some stuff that if he meant it exactly as he said, could feed into what’s called rape culture. And there’s nothing wrong with calling it exactly what it is. People may not like it. Or they may be confused by it – and anyone using that term has to decide whether they want to try and accommodate their audience, or simply call things what they are. That’s their decision, and they have to accept the consequences.

I also reject that it’s an “inflammatory” term. No. It’s not. It’s just a term that describes certain behaviors in relation to sexual violence. The fact that the term offends people does not make it inflammatory. It merely shows that we have an issue with addressing sexual violence. It’s like racism. You cannot talk about racism with some people, because the mere suggesting that something is “racist” is “so offensive”. No. Racism isn’t offensive. Saying racist things is offensive. Rape-culture isn’t inflammatory – people saying stuff that feeds into rape culture is inflammatory. Something like that.

Or to remove the discussion from less loaded topics, cancer sucks. It’s a horrible disease that kills many. But telling someone they have cancer is not inflammatory. If they do have cancer, then that’s just how it is. Even if cancer sucks really bad. So, if something is rape culture, why do I need to find a term that is less bothersome to people when that is the proper term to use for the issue at hand?

I already conceded that I may want to do that just for the sake of not losing people to my point. But that would be a nice thing of me to do. I’m not “wrong” for calling something what it is. Just as Elder Callister was ok with calling things what they were from his perspective.

Basically, I can accept that you may feel differently about Elder Callister’s talk than I did. That’s ok. But for me, as a woman, who’s grown up in the Church, and heard this rhetoric in many different ways (and many different languages), and has absorbed it, and with my combined knowledge of sexual violence against women, or more specifically “rape culture” – I wouldn’t say that he “sounded like victim blaming”. To me, he DID engage in victim blaming. And victim-blaming is part of rape-culture. And that’s just not cool.

“…it’s important to realize that we’re having that conversation in the midst of a greater battle.”

Nailed it.

You have a gift good sir. I appreciate your thoughtfulness both in your first two posts and in this follow up.

Nathaniel, it seems that, right after making it, you admit that MITM is probably not an apt metaphor (“This example is too obvious to be a really powerful man-in-the-middle attack.”) since the essence of MITM is that the MITM should be undetected.

You didn’t, in my opinion, get to the really valid critique against Callister’s terminology (which, as you’ll recall, I already pointed out), which is that it is uncommon and inappropriate usage. There is a perfectly good, widely understood, common word for masturbation, and it is … wait for it … masturbation! This is not just a “clinical” term. It is a popular non-slang term. This is the term he should have used.

The term he actually used is a non-standard throwback from Victorian times, when the French biologist, Tissot, very unscientifically claimed that masturbation caused wasting, insanity, and finally death. This alarming claim quickly developed into a sort of mass hysteria, very much like some of the pseudoscience you criticize in some of your other blog posts, despite the fact that it had not been proven, giving masturbation a much more negative connotation than it had previously, when it was thought of as a fairly common and relatively benign practice. The term “self abuse” implies that the person engaging in this behavior is inflicting upon themselves severe psychological and/or spiritual damage. Most psychologists agree that these stigmatic connotations are actually causing far more damage than the practice itself (which even takes place in the womb), and that different approaches to human sexuality are more likely to result in positive outcomes and healthy attitudes about sex.

This gets to the heart of what I believe Mormon therapists like Parker and Finlayson-Fife are arguing–that rhetoric like Callister’s is actually less likely to promote healthy, fulfilling sexual relationships between husbands and wives. In a religion that claims the husband-wife relationship to be a divine pattern and the highest order of godliness, the health of our inter-spousal relationships should be paramount, and yet therapists observe pervasive systemic problems that are significantly exacerbated by our religious subculture.

This gets right to the point you made earlier, using Elizabeth Smart and the sermon about the rose as examples. This type of rhetoric does a lot of damage, and there are better ways of approaching it. We should be focused on better ways of teaching the standards that are more conducive to the outcomes we desire.

Finally, I’d like to make a point that goes beyond my previous arguments. Please treat any responses to this last section separately from what I just said. My prior arguments stand on their own and I believe they demonstrate valid deficiencies in Callister’s argument and our general approach to sexual morality independent of the claims I will now make.

Beyond merely examining the extent to which our rhetoric is effective at upholding the standards, we should be willing to examine the extent to which the standards themselves promote the outcomes we desire. Even standards of sexual purity should be evidence-based. Commandments exist for reasons. While not everyone may be able to adequately articulate why they exist, if nobody can do so after an extended period of prayerful consideration, then we should have the courage to question their legitimacy. Many standards that were previously assumed to be God’s will ultimately ended up being shown to be deficient or even diabolical. One of the things that we are in constant danger of doing is to mistake religious symbols for the things they point to–to mistake human constructs for God. This is idolatry. Paul points out that the only thing that will endure forever is love, and that all other things will pass away or in some way or another wear out their usefulness. Joseph Smith teaches that commandments are contextual:

God is currently pouring down knowledge from on high in a plethora of ways, and it behooves us to recognize the ways in which this new knowledge challenges our preconceptions and be willing to adapt to the improved understanding that it brings. I quote from Adam Miller:

Like Miller, I believe it is clear that there are still “many great and important things” to be revealed, and that these things will sometimes challenge our preconceptions and demonstrate weaknesses in our present teachings and standards. I believe that to claim that the standards as we presently teach and understand them are optimal, static and eternal is to greatly err and to betray the further light and knowledge that God is presently pouring down upon us, and I don’t believe it is in the spirit of the restoration initiated by Joseph Smith.

I’m not interested, at present, in prescribing specific immediate changes to Church standards. I’m primarily interested in advocating for a greater willingness to accept and learn from the revelations of God, to live by what Joseph Smith called the “first grand fundamental principle of Mormonism, … to receive truth, let it come from whence it may.”

What, you think you can trust the kind of person who pulls off a man-in-the-middle attack? Eve is probably sleeping with the fishes…

Chris-

Well, when you think about it all communication is basically “mind-reading” by definition. So I don’t think I’m asking for anything unusual or special. Just a certain degree of open-mindedness and generosity in how we interpret what we hear.

This is true. So I guess the fight over (for example) the term “abuse” is more akin to signal-jamming than a man-in-the-middle attack.

I do think, however, that certain phrases (like “get the type of man they dress for”) do at least partially fit the man-in-the-middle approach. On the sending end, I don’t think Elder Callister had any conception that his words would be misconstrued. On the receiving end, I think some degree of the hurt felt by some of the listeners comes from applying what they take to be the objectively correct meaning of the phrase. So this really is the MITM attack: neither party is genuinely aware of the extent to which the other is using a different lexicon.

Well, a key point in my post (just so we’re clear) is that I don’t think you’re wrong to want for more sophistication in our dialogue. I just think we should be aware that what we’re going to end up with is going to be a compromise. It has to be. There are too many widely divergent groups within the audience. No one is going to get everything that they want out of discourse that happens on such a broad scale.

Thanks for joining the conversation! It’s probably no big surprise, but I am not convinced by your arguments.

Let’s take Elder Callisters “get the type of man you dress for” line. To me, this is a non-controversial summary of assortative mating. To you, this is victim-blaming. When you say that Elder Callister is at fault for miscommunicating, you are effectively saying that my viewpoint is invalid. What you perceive matters. What I perceive does not.

I think this is a factually incorrect theory of communication, for one thing, and a double standard for another. It’s factually incorrect because it ignores the reality that language is arbitrary. Words do not have objectively true meanings. Their meaning is purely conventional. They mean whatever we think they mean. Therefore, it doesn’t make sense to try and assign blame between a speaker / listener except in very unusual circumstances. It’s a double standard because you’re treating your own perception as privileged over the perceptions of others (like me).

(Your example of speaking German doesn’t work for precisely this reason. You’re assuming that words have some kind of intrinsic meaning independent of what the speaker intends or the listener perceives. That’s impossible. If you separate words from the context of human intention and perception all you have is noise or random lines.)

Just for contrast, my approach concedes that your perception of Elder Callister’s words is valid, but also suggests that mine is also valid. It allows for the possibility of mistakes that are no one’s fault, and it requires us to cooperate and compromise in order to communicate effectively.

Did Elder Callister miscommunicate? Yes, he did. Some of that could have been avoided. Some of that could not have been because communication is imperfect and because his audience has too wide a spectrum of perceptive paradigms. Did you miscommunicate when using the term “rape culture”? Yes, you did. Some of that you could have avoided. Some of that, as with Elder Callister, was inevitable.

If offending your audience matters, than it matters. You can’t say that it matters or not depending on whether you’re in the audience or not. Live by the offense, die by the offense.

And the term “rape culture” is certainly inflammatory. Once again: language doesn’t have objective meaning. The name wasn’t discovered the way Newton discovered Newtonian physics. It was a term that was chosen in the 1970s by a radical political ideology. They could have gone with any number of terms. They picked “rape culture” in no small part because it’s a big, bold, attention-getting term.

Carl-

I think there is some hold-over prudery going on in the refusal to put the word “masturbation” in the Ensign, but the simple reason to use the term “abuse” is to emphasize the fact that it is spiritually harmful.

It’s a stretch to start bringing up obscure Victorian-era French doctors and speculating about physical side-effects of masturbation. Why, in a talk about sexual morality, would we ever put spiritual effects on a back-burner to physical effects? The meaning of the phrase seems very self-evident, and I don’t understand the urge to skip over the simplest and clearest meaning of the word choice in favor of some exotic and convoluted theory.

That’s the first problem. The second is that you want to enlist Parker and others as sharing your concerns, but the arguments they have outlined do not align with yours. Her stated argument against the term “abuse” was that it was mis-using a clinical term. You seem reluctant to take her at her own word.

Are there “pervasive systemic problems that are significantly exacerbated by our religious subculture”? Yes. I wrote about some of them in this piece. The existence of such problems is not in question. The problem is in correctly identifying what those problems are, and in those cases Parker’s argument (and the others that I have read) fall short because they present neither sound reasoning nor empirical evidence to substantiate their accusations.

It is possible that some of the folks who share similar concerns as you do not actually share a common rationale for arriving at those concerns. (This is a frustrating and familiar experience for me.)

Before I respond to this directly, I just want to emphasize the fact that you’re far, far from the first person who has told me that the problem isn’t with the standards, but in how we talk about them, and who has subsequently added as a follow-on that you also happen to question the standards.

I do not take it for granted that, in questioning the standards, you invalidate your position. I do not take it as an axiom that every standard we currently have in our Church is eternal. The Church has had policies that were mistaken in the past, and we may discover new ones in the future. This is very likely to happen as globalization forces us to think harder about what aspects of our faith are truly doctrinal and what aspects are cultural.

So, in principle, I agree. Your argument is unnecessary because I’m already on board.

However, my position is that attempts to reform sexual standards are, as a matter of actual fact, wrong. You write that:

I think that’s a fine starting point, but when it comes to the actual matters in question (things like masturbation, homosexual sex, and so forth) I do not think that they come remotely close to passing your test. There is deep and profound theology and philosophy to substantiate traditional sexual morals. When we get to the point where “nobody can adequately articulate why they exist,” let’s talk, but in reality it all comes down to assessing “adequate” doesn’t it?

From my point of view, the arguments in favor of having sexual relations restricted to only married, heterosexual spouses is sublime and profound. From your perspective, perhaps, nobody can adequately give any defense of this position at all.

I won’t try to resolve that difference. I will just point out that your initial criticism (which is that we can have an argument about how we talk about these standards without calling the standards themselves into question) seems seriously undermined by the fact that many of those who are most vociferous in their criticisms of the “how” are also the folks most in favor of changing the “what”.

That was a major point of this post, and I think you’ve strongly corroborated it here.

Poor Eve :(

https://xkcd.com/177/

Nathaniel, really, that wasn’t nice. I went to great lengths to make it clear that my argument is divided into two independent sections and stated my belief up front that either position is valid in isolation. In other words, even if the standards are perfect as-is, it is still theoretically possible that the way we teach them is not. AND if the standards are not perfect as-is, there is additional work for us to do. These arguments do not depend on one another, nor are they invalidated by one another. Your claim to the contrary really is a treacherous reading of my position. If you can’t at least state my position in a way that I would agree with, we can’t really have a meaningful dialogue.

Regarding the cultural perception of masturbation, the term “self abuse” really does come from this era, so I don’t find the reference obscure at all. If you read the history of the cultural perception of the practice, you’ll learn that much of the stigma around it, both in spiritual and physical terms, traces back to this era. I think that this cultural perception is highly influential on individuals’ personal perception of it as well.

Here again you are distorting my position and conflating several issues. I never claimed that a single standard should be relaxed, so why assume the worst? I too am in favor of monogamy and chastity. My point was rather that we should be able to provide good reasons for obeying the commandments that are not merely because they are aesthetically pleasing on a personal level.

Incidentally, if you do have a good defense of why gays should not be allowed to marry (at least civilly, if not as members in full standing) please share it. I would like to understand your position better.

Carl-

I am confused. I thought that I was being very careful to respect your position, but your response (“Really, that wasn’t nice,”) indicates that my execution was lacking.

From what I could tell, you argument was that we should be open to lowering some standards based on new evidence, and I take it that you are at least somewhat in favor of specifically lowering / changing standards when it comes to issues of masturbation and homosexual relations.

So, I was actually trying to be generous in granting that such speculation is not in and of itself, grounds to discount your argument.

What did I miss?

Carl-

There are several organizations and thinkers that I think do a pretty good job of outlining the case. One prominent example is the article “What Is Marriage?” from the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy which you can find here: http://www.harvard-jlpp.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/GeorgeFinal.pdf

I may have misunderstood your language, but when you “I do not take it for granted that, in questioning the standards, you invalidate your position.” I thought you were saying that by merely mentioning that standards should be scrutinized I was invalidating my position. If this is not what you were saying, please elaborate.

Yeah, I meant the exact logical opposite of what you understood. :-) I was specifically saying that I did not believe that you had invalidated your position by questioning the standards.

This.

OK, sorry about that.

@Nathaniel – I must say I find these conversations absolutely suffocating! I agree with your position, but the elaborate lengths to which you go to meet unreasonable critics halfway seems like it ‘only encourages them’!

What gets lost in these discussions is the really important bits of what used to be common sense wisdom but which are now un-sayable ‘hate facts’ like: “…women get the type of man they dress for.”

Such things should not need saying, because they are very-obviously-true generalizations necessary for social competence and safety – but in fact they do need saying: and they need saying very starkly and plainly and without hedging or softening.

Because so many women live in a culture which denies the plain truth of “women get the type of man they dress for” – what actually happens is that plenty of women do not get the men they most want or need; but instead get “the type of men they dress for”.

This is happening to women, but they are surrounded by people (especially people in or connected with the mass media – i.e. the greatest force for the promotion of evil in the modern world) who claim that it is *not* happening – therefore nothing should be done about it; no corrective action should be or is taken.

Causes have effects, choices have consequences; true generalizations are true and are vital – and they are not refuted by exceptions:

http://charltonteaching.blogspot.co.uk/2014/03/a-lie-versus-true-generalization.html

Bruce,

I’ve been reading more conservative voices lately (for random reasons), including conservative sci-fi authors like Larry Correia and John C. Wright (samples here and here.) Matt Walsh, quoted in that example from John C. Wright is another example. I admire the clarity of their writing and, to be perfectly frank, it makes me nostalgic.

I feel a little bit like an exile because that kind of red-blooded social conservatism is kind of my home, but my own writing makes me an object of suspicion to folks like that, even when I’m writing in defense of common values. It reminds me of Adam G’s description of me as “something of a squish” even while agreeing, more or less, with something I’d written. (Here.) That may not have been the thrust of your observation that “the elaborate lengths to which you go to meet unreasonable critics halfway seems like it ‘only encourages them’!” but if it was the thrust, it would be par for the course.

My own perspective is two-fold. First, I’m constantly thinking about a scripture from D&C 123:12:

If we take that universality seriously, and I do, then it would suggest that we can find good and sincere people of every political persuasion. I want to be able to talk to them not just about them (or their politics.)

I also think that while a lot of the most important, most beautiful, and most true principles in the world are, or at least should be, simple, self-evident, and maybe even stark, we’re not always so good at separating between the principles and our own preferences.

Sometimes you’re talking to the person who has been blinded, and sometimes you are the person who has been blinded.

As best I can figure it, there isn’t one true way to talk about religion and politics. I think that the folks who are just out there doubling-down on the core principles, as it were, are fulfilling a role. I don’t think my particular brand of squishiness ought to become universal. But by the same token I hope that it does fulfill an important role. I could be kidding myself, I know, but I like to think that building bridges isn’t a waste of time or necessarily a sign of weakness.

When it comes down to it, some of my critics are people I really trust and admire. I feel strongly that they deserve a serious response, and when I concede that their criticisms have validity I’m not engaging in politicking by way of false-equivalence. My outrage at the anti-Christian message of “purity culture” is every ounce as real at my umbrage at the anti-Christian message of lowering standards until everyone gets a trophy. And even when I think that the logic of a statement like “get the kind of man you dress for” is fairly obvious and uncontroversial, I recognize that there are some people who are hurt by that statement.

In the final analysis, however, I do assign a lot of the blame for the hurt to the messages of mass media. In plain terms: I find the acceptance of casual sex to be genuinely misogynistic in its effect and that “man-in-the-middle” stuff I tacked on the end weighs heavily on my mind.

But what good does it do me to come back and tell folks who are already in the know on these issues how right they are? It’s fun, I guess, and I can’t deny that I engage in it from time-to-time, but my hope is always to be able to reach the folks who don’t already know.

Geez… I can’t write anything short, can I?

Nathaniel

I have always been pretty abrasive and combative in public discourse (as the internet records, going back to when I started writing in New Scientist in 1987), and been in various types of trouble about it – but it didn’t stop me changing from a hardline atheist to a (similarly unsubtle?) Christian at about age 49; and John C Wright has a similar style and a similar intellectual trajectory. I move from one ‘infallible’ statement to another…

My observation is that squishes are (empirically) less likely to be persuaded and repent than hardliners (perhaps due to a fatal lack of clarity which never gets the point of generating an explicit contradiction) – squishes nearly-always seem to slide Apostasy/Left/ Liberal-wards. (So I hope you aren’t one; or if you are then I hope you hold-on tight and don’t start sliding…!)

After a couple of decades of polemics, I don’t think engaging in arguments do much good – but clear statements of conviction sometimes lodge in the mind and do their work – at least that is my experience.

At present I am only a theoretical Mormon, but insofar as I am able to contribute anything at all in this line, it may be because I have a different style than most Mormons. GK Chesterton did his best Roman Catholic Apologetics before he actually joined the RCC (not that I am comparing my ability with GKC! – but if or when I become LDS, I have a feeling that I will not stop feeling the need to write about Mormonism.)

BTW – I have a 25K word mini-book called Addicted to Distraction coming out in a few months in which (inter alia) I argue that the Mass Media is the primary source of evil in the modern/ Western world – If you are interested I could send you the corrected first draft as a (Windows 7 docx) word file if you e-mail me hklaxness^yahoo^com

“To the extent that secular politics (from any end of the spectrum) start to change the way we perceive the words we hear, there’s a risk that we’re starting to lose contact with the General Authorities”

Ironically, I think this kind of perception shift can actually end up giving rape culture more power. The more you focus on a problem (or perceived problem), the victimization of those the philosophies are trying to protect only continues and gets more embedded in the culture. It also shifts the responsibility ‘out there’ instead of helping empower victims to find strength and healing from within their own circles of influence and control.

Thanks for this piece.