This is one of those blog posts that, once you’ve read it, makes you wonder how there was ever a possible universe in which you didn’t know the concepts that you just learned: The Heat Death of Humanity: Progressivism as the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The first major new concept has a humble name: paperclipper. According to the Less Wrong Wiki[ref]I have no idea[/ref], the paperclipper is “the canonical thought experiment showing how an artificial general intelligence, even one designed competently and without malice, could ultimately destroy humanity.” Imagine, as the original 2003 paper did, an AI given the task of maximizing the number of paperclips it has in its collection. Seems harmless enough at first glance. However:

If it has been constructed with a roughly human level of general intelligence, the AGI [artificial general intelligence] might collect paperclips, earn money to buy paperclips, or begin to manufacture paperclips. Most importantly, however, it would undergo an intelligence explosion: It would work to improve its own intelligence, where “intelligence” is understood in the sense of optimization power, the ability to maximize a reward/utility function—in this case, the number of paperclips. The AGI would improve its intelligence, not because it values more intelligence in its own right, but because more intelligence would help it achieve its goal of accumulating paperclips. Having increased its intelligence, it would produce more paperclips, and also use its enhanced abilities to further self-improve. Continuing this process, it would undergo an intelligence explosion and reach far-above-human levels. It would innovate better and better techniques to maximize the number of paperclips. At some point, it might convert most of the matter in the solar system into paperclips.

Or, in the words of Eliezer Yudkowsky, “The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of atoms which it can use for something else.” In this case: paperclips.

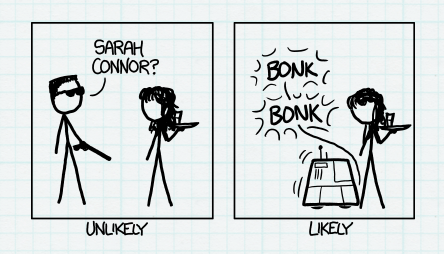

Keep that example in mind for a moment, and think about recent critiques of the social justice movement: Chait’s, Ronson’s, or (what the heck), mine. The common thread is that there is no limiting principle to halt the downward spiral of ever increasing levels of outrage over ever smaller indignities. This doesn’t mean that the individual progressive causes are wrong. The problem is that–just as with the paperclipper–a benign (or even good!) goal has been mistaken for the only goal. Justice is the paperclip.

Well, obviously justice is a lot more intrinsically valuable than a paperclip (or any number of paperclips), but the fact remains that it isn’t the only goal. And justice at the expense of truth, or at the expense of mercy and forgiveness, or at the expense of any number of other possible virtues can become just as dangerous as the paperclipper.

There’s more to the story, however. The primary source of energy for the social justice movement is outrage, and the outrage is derived from examples of injustice. The more injustice the movement sees, the more energy it has available. To use a biological metaphor: here you have a bunch of leaf-eating herbivores and along comes an herbivore that can eat entire trees (bark, branches, and even trunks). The new organism is going to out-compete and eventually replace all others. But, in our case, the same feature that makes social justice ideology so perfectly adapted to our memetic ecosystem is also fueling a kind of second law of thermodynamics for social systems.

It seems that perhaps progressivism is the embodiment in human systems of the second law of thermodynamics, which can be roughly stated as “the tendency of natural processes to lead towards spatial homogeneity of matter and energy, and especially of temperature.”

The individual differences that social justice seeks to ameliorate may be, case-by-case, well worth the effort of amelioration. Or even eradication. But without a limiting principle, the risk is that all differences will be eradicated. And that’s bad because”

…If you even care about life existing – let alone the infinite diversity possible therein – then (contra Caplan), boundaries (such as national borders) are an absolute necessity. No differences, no energy flow, no (thermodynamic) work, no life. As in the stars, so on the earth: romance flows from polarity; trade from comparative advantage; thermodynamic work from heat differences;evolution from variation; economic competition from competing alternatives. All progress is driven by differences; so to erase differences is (counter-eponymously) to end progress.

A lot of this is argument-from-metaphor, of course, which is always perilous. But I certainly think there is some validity to this approach.

Despite the Platonic ideal, ordinary people do not spend the majority of their time in the act of deep contemplation. Instead, they are performing the seemingly menial tasks of daily life. This largely consists of one’s form of employment. Finding meaning in the lone and dreary world of day-to-day work has been a point of increasing interest among management experts and organizational theorists. Their findings yield fruitful insights, especially given that one of Mormonism’s earliest forms of consecration was a business organization known as the United Firm. The “inspired fictionalization” of the United Firm revelations is an early example of Joseph Smith’s cosmological monism, transforming a business entity into the ancient “order of Enoch.” This sacralization of the mundane was further elaborated by Brigham Young and recognized by non-Mormons as an oddity of the Utahns. The metaphysical overlap of the temporal and spiritual realms can influence the way modern Mormons conduct their business, inspire “Zion-building” within organizations, and pave the way for a Mormon theology of work and eternal progression.

Despite the Platonic ideal, ordinary people do not spend the majority of their time in the act of deep contemplation. Instead, they are performing the seemingly menial tasks of daily life. This largely consists of one’s form of employment. Finding meaning in the lone and dreary world of day-to-day work has been a point of increasing interest among management experts and organizational theorists. Their findings yield fruitful insights, especially given that one of Mormonism’s earliest forms of consecration was a business organization known as the United Firm. The “inspired fictionalization” of the United Firm revelations is an early example of Joseph Smith’s cosmological monism, transforming a business entity into the ancient “order of Enoch.” This sacralization of the mundane was further elaborated by Brigham Young and recognized by non-Mormons as an oddity of the Utahns. The metaphysical overlap of the temporal and spiritual realms can influence the way modern Mormons conduct their business, inspire “Zion-building” within organizations, and pave the way for a Mormon theology of work and eternal progression.

A

A