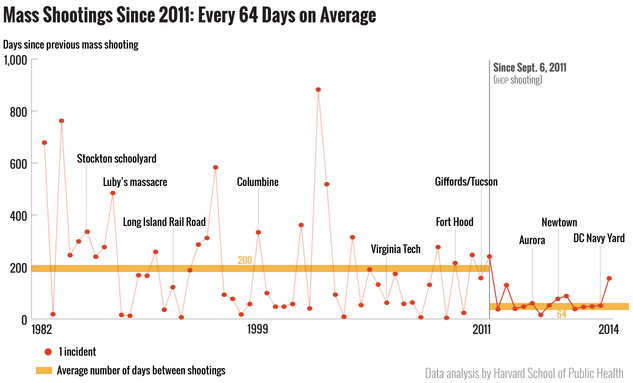

Damon Linker has a good piece about the violence of mass shootings: Men and mass murder: What gender tells us about America’s epidemic of gun violence. Most perpetrators of violence in all societies (this is one of those social universals) are men, and mass shooters are no exception: “Murder is an overwhelmingly male act, with the offender proving to be a man 90 percent of the time the person’s gender is known. When it comes to mass shootings, the gender disparity is even greater, with something like 98 percent of them perpetrated by men.”

So, first there’s a connection between men and mass shootings. Then Linker goes one step farther and links a particular male response to perceived grievance:

Men and women both experience righteous indignation, of course. But there may be something specific about masculinity — perhaps its deep ties to irrational pride — that leads some men to experience a perceived injustice (and especially a string of them) as an excruciating personal humiliation that cries out not just for redress but for revenge. In this way, wounded pride provokes some men to lash out in a violent fury at their fellow human beings as a way of striking back at the intolerable injustice of the world.

And then he stops. Which is a shame. He should have kept going.

Because there’s another trait that mass shooters have in common: fatherlessness. Peter Hasson covered this for The Federalist: Guess Which Mass Murderers Came From A Fatherless Home. He cites a Brad Wilcox National Review article from 2013 (Sons of Divorce, School Shooters) in which Wilcox says:

From shootings at MIT (i.e., the Tsarnaev brothers) to the University of Central Florida to the Ronald E. McNair Discovery Learning Academy in Decatur, Ga., nearly every shooting over the last year in Wikipedia’s ‘list of U.S. school attacks’ involved a young man whose parents divorced or never married in the first place.

Let me pull in just one more article and then make some final observations. This one is from Sue Shellenbarger in the WSJ: Roughhousing Lessons From Dad. Shellenbarger starts out with an incredibly important observation:

There is no question among researchers that fathers who spend time with their children instill self-control and social skills in their offspring.

If you could name just two traits to lessen the likelihood that a young man ever considers school shootings as the solutions to his life’s problems, these would be the two traits. Social skills to avoid a lot of the alienation and failure that engenders the grievances in the first place, and to help these young men find constructive ways to deal with those grievances that do arise. And self-control to ensure that any grievances which cannot be ameliorated do not become a basis for action.

Everyone wants to find the one solution that’s going to solve school shootings. There isn’t one solution. No complex social problem has a simple, easy solution.[ref]That might not be a law of nature, but it’s a pretty good rule of thumb.[/ref] In particular, gun control debates basically do nothing but make people angry and waste our time. That’s not to say that we should not change our gun laws. There are actually very good arguments–philosophical and practical–for changing gun laws. School shootings, however, are not among those arguments. The basic reason for this is straightforward: most school shootings are premeditated. This means the killer has lots of time to acquire a gun. Most do so legally, passing background checks (which can’t screen for crimes you haven’t committed yet) and following all applicable laws. Those that do not, have the time and the means to acquire them illegally. So the only gun control laws that would do anything are gun control laws that would significantly decrease the availability of guns in the long term. Considering that there are more firearms than human beings in this country, nothing short of a massive, nation-wide confiscation program is going to put a dent in the practical availability of firearms, and therefore nothing that falls short of that is going to have a meaningful impact on the specific type of crime we’re talking about here.Such a sweeping change is not on the table.

Now, I understand a lot of folks will want to push back and insist that there are common sense changes we can make that will help at least a little bit. There really aren’t. Not when it comes to school shootings. When it comes to other gun-related problems–from suicide to gang violence–there is certainly a lot to talk about. I’m not trying to shut down the debate by claiming that laws don’t matter. Obviously, in general, they do. But in the specific case of school shootings–due to the nature of the attacks and the attackers–most incremental changes will have no effect. Add a waiting period? These guys are planning their attacks months or years in advance anyway. Close the gunshow loophole? Most of the shooters acquired their guns by going through the background check process. They didn’t need the loophole. Ban assault weapons? Almost all attacks use handguns anyway, including the deadliest. Reduce the magazine capacity? There is no practical difference in lethality–when attacking unarmed civilians–between a standard 15-round magazine and a low-capacity 10-round magazine. The deadliest school shooter used a mixture of 19 pre-loaded 10- and 15-round magazines. If they’d all been 10-round magazines, he would have maybe carried a few more and maybe reloaded a little more often. (It takes less than a second or two.)

So if you want to debate gun policy: that’s fine. There is lots to talk about. But insisting that incremental policies will have an effect in this particular case is just wishful thinking. I’m sorry, but that’s the reality.

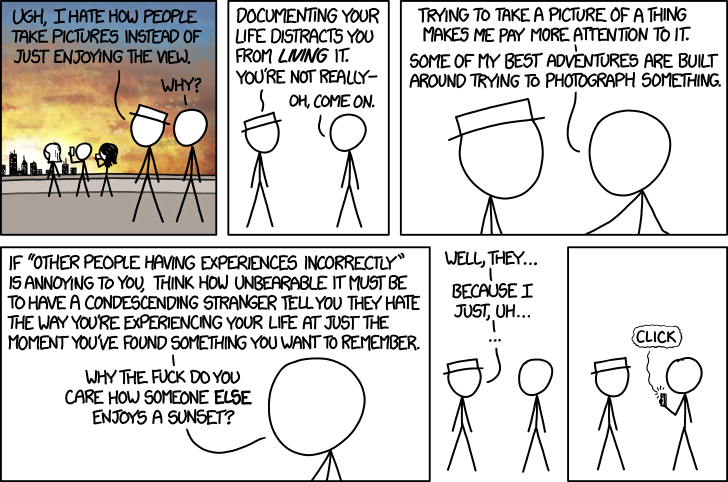

But that doesn’t mean we are helpless to do anything. It just means that laws are not the solution to all social problems. I don’t think that that should really be a revelation, but in some sense it is. We love politics because it’s a spectator sport. It has a score. It has winners and losers. It has teams, and traditions, and tribes, and flags, and symbols, and so naturally it occupies a huge amount of our attention. Too much, I think.

The older I get, the more I think that it’s the quiet, informal, decentralized aspects of our society that are the most important. The traditions, the habits, the expectations, and the attitudes of a people matter a lot more than their laws. And there is room for us to make changes there. The only problem is that, because they happen at the individual level, they are not connected to an exciting sports spectacle. And, in addition, there is really no guarantee that our efforts will have any impact. But I think it’s the only thing that can really help maintain the aspects of our society we cherish and restore or fix the aspects that are broken.

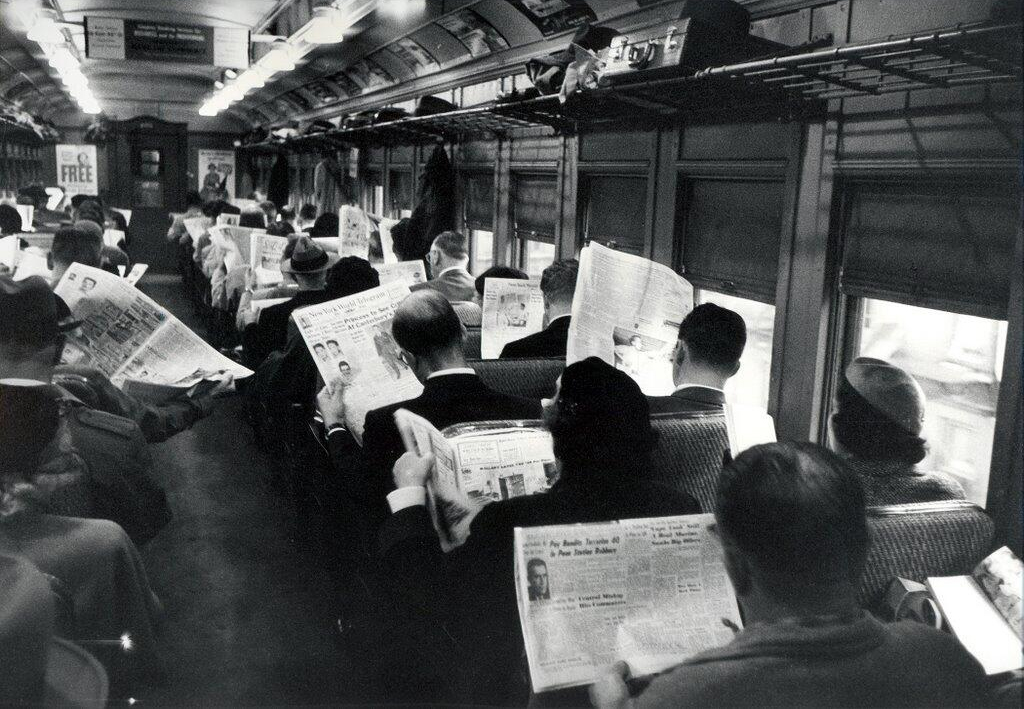

I already posted about the danger of glorifying the mass killers. That’s not a legal change. That’s not a policy change. That’s a social change. It’s enough people–one at a time–deciding to turn off 24-hour cable news coverage, steer clear of clickbait and rumors and conspiracy theories, and opt out of lurid headlines full of details about the killers: their names, their pictures, their backgrounds, their manifestos, all of it.

Even bigger than that is the crisis of fatherlessness in our society. Kids need parents. They need mom. They need dad. We as a society have to figure out how to stem the tide of kids growing up without the irreplaceable guidance and influence of their fathers. We’re paying an incredibly high price for a lax attitudes about sex and parental responsibility that have time and time again placed the interests of adults above the interests of children. As time goes on, that price tag is only going to get higher. School shootings are just one particular symptom.