An intriguing article by economists Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson (based on their new book) traces the history of American income inequality. While some suggest that inequality is driven by a “fundamental law of capitalist development,” it turns out that “episodic shifts in five basic forces” to to blame: “demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change.” The following took me by surprise:

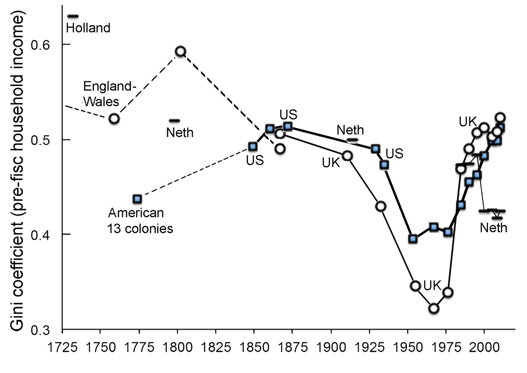

Colonial America was the most income-egalitarian rich place on the planet. Among all Americans – slaves included – the richest 1% got only 8.5% of total income in 1774. Among free Americans, the top 1% got only 7.6%. Today, the top 1% in the US gets more than 20% of total income. Colonial America looks even more egalitarian when the comparison is by region – in New England the income Gini co-efficient was 0.37, the Middle Atlantic was 0.38, and the free South 0.34. Today the US income Gini is more than 0.5, before taxes and transfers. Colonial America was also far less unequal than Western Europe. England and Wales in 1759 had an income Gini of 0.52,and in 1802 it was 0.59. Holland in 1732 had an income Gini of 0.61, and the Netherlands in 1909 had 0.56. Also, if you agree with neo-institutionalists that economic equality fosters political equality, which fosters pro-growth policies and institutions, then America’s huge middle class is certainly consistent with the young republic’s pro-growth Hamiltonian stance from 1790 onwards. That is, the middle 40% of the distribution got fully 52.5% of total income in New England, the cradle of the revolution!

However, inequality began to rise between 1800 and 1860, “matching the widening income gaps we have witnessed since the 1970s. The earlier rise was not dominated by a surge in the property income share, as argued by Piketty (2014). Rather, this first great rise in inequality was broadly based, with widening income gaps throughout the whole income spectrum – rising urban-rural income gaps, skill premiums, gaps between slaves and the free, North-South income gaps, earnings inequality, and even property income inequality.”

Yet,

the income share captured by the richest 1% fell dramatically between the 1910s and the 1970s, and the share of the bottom half rose, for almost all countries supplying the necessary data. This ‘Great Levelling’ took place for several reasons. Wars and other macro-shocks destroyed private wealth (especially financial wealth) and shifted the political balance toward the left. The labour force grew more slowly and automation was less rapid, improving the incomes of the less skilled. Rising trade barriers lowered the import of labour-intensive products and the export of skill-intensive products, favouring the less skilled in the lower and middle ranks. And in the US, the financial crash of 1929-1933 was followed by a half century of tight financial regulation, which held down the incomes of those employed in the financial sector and the net returns reaped by rich investors.

The authors note that “policies regarding education, financial regulation, and inheritance taxation…offer ways to check the rise of inequality while also promoting growth.” It is worth pointing out that this is about inequality and not about the absolute economic betterment of the average American. Nonetheless, understanding this economic history is important for those on both the right and the left.

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been

Most people are in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar, yet many supporters tend to look at natural gas with disdain.[ref]Arguably due to the means of its extraction (fracking). For example, there’s been

Calestous Juma, Professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, has a

Calestous Juma, Professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, has a