Released by WOWARMENIA for Wikimedia under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license

I didn’t get a chance to make that pithy observation in a Facebook exchange this morning because my interlocutor gave me the boot. That’s OK, I may have been blocked from somebody’s Facebook feed for thinking bad thoughts, but I can’t get blocked from my own blog! You can’t stop this signal, baby.

So, just as two wrongs don’t make a right, let’s use this Columbus Day to talk about two stupids that don’t make a smart.

Bad Idea 1: The Noble Savage

There’s a school of thought which holds, essentially, that everything was fine and dandy in the Americas until the Europeans came along and ruined it. The idea, seen in Disney and plenty of other places, is that “native” peoples lived at harmony with the Earth, appreciating the fragile balance of their precious ecosystems and proactively maintaining it. This idea is bunk. The reality is that in almost all cases the only limit on the extent to which any culture restricts its exploitation of natural resources is technological. Specifically, humanity has an unambiguous track record of killing everything edible in sight as they spread across the globe, leading to widespread extinctions from Australia to the Americas and upending entire ecosystems. If our ancient ancestor didn’t wipe a species out, the reason was either that it didn’t taste good or they couldn’t. As Yuval Noah Harari put it Sapiens:[ref]Which I reviewed here.[/ref]

Don’t believe the tree-huggers who claim that our ancestors lived in harmony with nature. Long before the Industrial Revolution, homo sapiens held the record among all organisms for driving the most plant and animal species to their extinctions. We have the dubious distinction of being the deadliest species in the annals of biology.

Harari specifically describes how the first humans to discover Australia not only wiped out species after species, but–in so doing–converted the entire continent into (pretty much) the desert it is today:

The settlers of Australia–or, more accurately, its conquerors–didn’t just adapt, they transformed the Australian ecosystem beyond recognition. The first human footprint on a sandy Australian beach was immediately washed away by the waves, yet, when the invaders advanced inland, they left behind a different footprint. One that would never be expunged.

Matt Ridley, in The Origins of Virtue, lists some of the animals that no longer exist thanks to hungry humans:

Soon after the arrival of the first people in Australia, possibly 60,000 years ago, a whole guild of large beasts vanished — marsupial rhinos, giant diprotodons, tree fellers, marsupial lions, five kinds of giant wombat, seven kinds of short-faced kangaroos, eight kinds of giant kangaroo, a two-hundred-kilogram flightless bird. Even the kangaroo species that survived shrank dramatically in size, a classic evolutionary response to heavy predation.

And that pattern was repeated again and again. Harari again:

Mass extinctions akin to the archetypal Australian decimation occurred again and again in the ensuing millennia whenever people settled another part of the outer world.

Have you ever wondered why the Americas don’t have the biodiversity of large animals that Africa does? We’ve got some deer and bison, but nothing like the hippos, giraffes, elephants, and other African megafauna. Why not? Because the first humans to get here killed and ate them all, that’s why not. There’s even a name for what happened: the Pleistocene overkill. Back to Ridley:

Coincident with the first certain arrival of people in North America, 11,500 years ago, 73% of the large mammal genera quickly died out… By 8000 years ago, 80% of the large mammal genera in south America were also extinct — giant sloths, giant armadillos, giant guanacos, giant capybaras, anteaters the size of horses.

In Madagascar, he notes that “at least 17 species of lemurs (all the diurnal one is larger than 10 kg in weight, one as big as a gorilla), and the remarkable elephant birds — the biggest of which weighs 1000 pounds — were dead within a few centuries of the islands first colonization by people in about 500 A.D.” In New Zealand, “the first Maoris sat down and ate their way through all 12 species of the giant moa birds. . . Half of all new Zealand’s indigenous land birds are extinct.” The same thing happened in Hawaii, where at least half of the 100 unique Hawaiian birds were extinct shortly after humans arrived. “In all, as the Polynesians colonized the Pacific, they extinguished 20% of all the bird species on earth.”

Ridley’s myth-busting doesn’t end there. He cites four different studies of Amazon Indians “that have directly tested their conservation ethic.” The results? “All four rejected the hypothesis [that the tribes had a conservation ethic].” Moving up to North America, he writes that “There is no evidence that the ‘thank-you-dead-animal’ ritual was a part of Indian folklore before the 20th century,” and cites Nicanor Gonsalez, “At no time have indigenous groups included the concepts of conservation and ecology in their traditional vocabulary.”

This might all sound a little bit harsh, but it’s important to be realistic. Why? Because these myths–no matter how good the intentions behind them–are corrosive. The idea of the Noble Savage is intrinsically patronizing. It says that “primitive” or “native” cultures are valuable to the extent that they are also virtuous. That’s not how human rights should work. We are valuable–all of us–intrinsically. Not “contingent on passing some test of ecological virtue” (as Ridley puts it.)

Let me take a very brief tangent. Ridley’s argument here (as it relates to conservation) is exactly parallel to John McWhorters linguistic arguments and Steven Pinker’s psychological arguments. In The Language Hoax, John McWhorter takes down the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis,[ref]AKA “linguistic relativity“[/ref] which is the trendy linguistic theory that what you think is determined by the language you think it in.[ref]You may have seen a meme about early humans not being able to see the color blue because the word for it appears later in most languages. This is precisely the kind of pseudo-scientific bunk McWhorter dismisses in the book.[/ref] Just like the Noble Savage, this idea was originally invented by Westerners on behalf of well, everybody else. The idea is that “primitive” people were more in contact with the timeless mysteries of the cosmos because (for example) they spoke in a language that didn’t use tense. Not only did this turn out to be factually incorrect (they just marked tense differently, or implied it in other cases, as many European languages also do), but it’s an intrinsically bad idea. McWhorter:

In the quest to dissuade the public from cultural myopia, this kind of thinking has veered into exotification. The starting point is, without a doubt, I respect that you are not like me. However, in a socio-cultural context in which that respect is processed as intellectually and morally enlightened, inevitably, to harbor that respect comes to be associated with what it is to do right and to be right as a person. An ideological mission creep thus sets in. Respect will magnify into something more active and passionate. The new watchcry becomes, “I like that you are not like me,” or alternately, “What I like about you is that you are not like me.” That watchcry signifies, “What’s good about you is that you are not like me.” Note however, the object of that encomium, has little reason to feel genuinely praised. His being not like a Westerner is neither what he feels as his personhood or self-worth, nor what we should consider it to be, either explicitly or implicitly.

The cute stories about the languages primitive peoples speak and the ways that enables them to see the world in unique and special ways end up being nothing but a particularly subtle form of cultural imperialism: our values are being used to determine the value of their culture. All we did was change up the values by which we pass judgement on others. Thus: “our characterization of indigenous people in this fashion is more for our own benefit than theirs.”

The underlying premise of Harrari, Ridley, and McWhorter is what Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate tackles directly: the universality of human nature. We can best avoid the bigotry and discrimination that has marred our history not by a counter-bigotry that holds up other cultures as special or superior (either because they’re in magical harmony with nature or possess unique linguistic insights) but by reaffirming the fact that there is such a thing as an universal, underlying human nature that unites all cultures.

Universal human nature is not a byproduct of political wishful thinking, by the way. Steven Pinker includes as an appendix to The Blank Slate a long List of Human Universals compiled by Donald E. Brown in 1989. It is a long list, organized alphabetically. To give a glimpse of the sorts of things behaviors and attributes common to all human cultures, here are the first and last items from the list:

- abstraction in speech and thought

- actions under self-control distinguished from those not under control

- aesthetics

- affection expressed and felt

- age grades

- age statuses

- age terms

- …

- vowel contrasts

- weaning

- weapons

- weather control (attempts to)

- white (color term)

- world view

The list also includes lots of stuff about binary gender which is exactly why you haven’t heard of the list and why Steven Pinker is considered a rogue iconoclast. These days, one does not simply claim that gender is binary.

I’ve spent a lot of time on the idea of the Noble Savage as it relates to ecology, but of course it’s a broader concept than that. I was once yelled at quite forcibly by a presenter trying to teach us kids that warfare did not exist among pre-Columbian Native Americans. I was only 11 or 12 at the time, but I knew that was bs and said so.[ref]He cursed me with the fires of Hell if I didn’t stop interrupting. I didn’t stop. The next day I got third degree burns. True story; I’ve still got the scars. He may have been a wizard, but I was still right.[/ref]

The point is that the whole notion of a mosaic of Native Americans living in peace and prosperity until the evil Christopher Columbus showed up and ruined everything is a bad idea. It’s stupid number 1.

Bad Idea 2: Christopher Columbus is Just Misunderstood

So, this is the claim that started the discussion that got me blocked by somebody on Facebook today. The argument, such as it was, goes something like this: Columbus looks very bad from our 21st century viewpoint, but that’s an unfair, anachronistic standard. By the standards of his day, he was just fine, and those are the standards by which he should be measured.

The problem with this idea is that, like the first, it’s simply not true. One of the best, popular accounts of why comes from The Oatmeal. In this comic, Matthew Inman contrasts Columbus with a contemporary: Bartolomé de las Casas. While Columbus and his ilk were off getting to various hijinks including (but not limited to) child sex slavery and using dismemberment to motivate slaves to gather more gold, de las Casas was busy arguing that indigenous people deserved rights and that slavery should be abolished. Yes, at the time of Columbus.

The argument that if we judge Columbus by the standards of his day he comes out OK does not hold up. We can find plenty of people at that time–not just de las Casas–who were abolitionists or (if they didn’t go that far) were critical of the excessive cruelty of Columbus and many like him. Keep in mind that slavery had been a thing in Europe for thousands of years until the Catholics finally stamped it out around the 10th century. So it’s not like opposition to slavery is a modern invention. When slavery was restarted in Africa and then the Americas many in the Catholic clergy opposed it once again, but were unable to stop it. So the idea that–by the standards of his day–Columbus was just fine and dandy doesn’t work. He’s a pretty bad guy in any century.

Two Stupids Don’t Make a Smart

I understand the temptation to respond to Noble Savage-type denunciations of Christopher Columbus by trying to defend the guy. You see somebody making a bad argument, and you want to argue that they’re wrong.[ref]Throw in the obviously implied left/right dichotomy and you’ve got partisan tribal motivations to boot![/ref]

But that isn’t how logic actually works. A broken clock really is right twice a day, and a bad argument can still have a true conclusion. If I tell you that 2+2 = 4 because Mars is in the House of the Platypus my argument is totally wrong, but my conclusion is still true.

The Noble Savage is a bad bit of cultural luggage we really should jettison,[ref]Especially when it results in bad Chipotle burritos, among other reasons.[/ref] but Columbus is still a bad guy no matter how you slice it. Using one stupid idea to combat another stupid idea doesn’t actually enlighten anyyone.

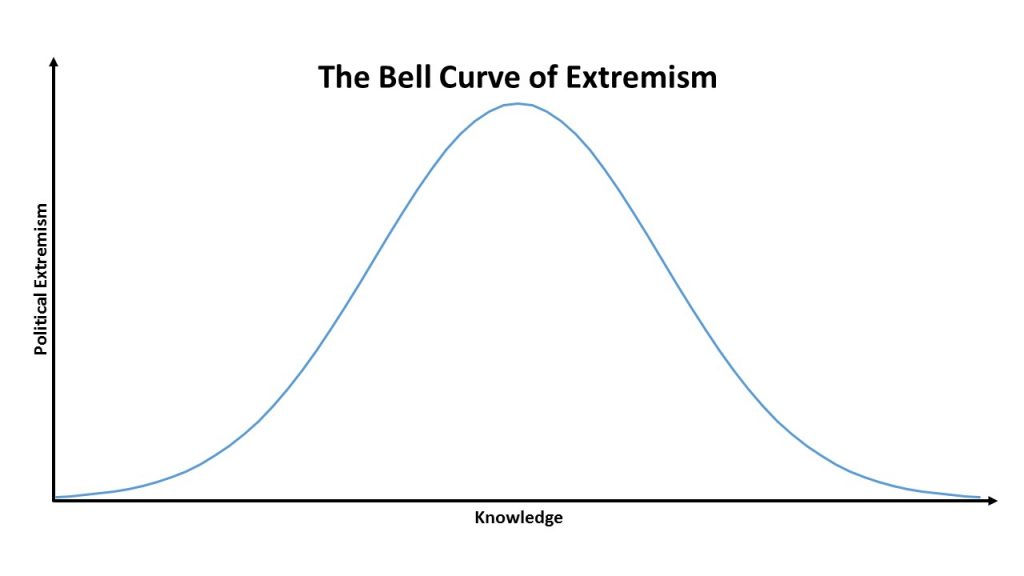

The Bell Curve of Extremism

There are basically two kinds of moderates / independents: the ignorant and the wise. It really is a sad twist of fate to stick the two together, but nobody honest every said life was fair.

To illustrate, let me introduce you to a concept I’ll call the Bell Curve of Extremism:

To flesh this out, I’ll use some examples from voting.

A person on the left doesn’t know who they’re going to vote for because they don’t know much of anything at all. They may not even know who’s running or who’s already in office. This doesn’t mean they’re stupid, necessarily. They could be brilliant, but just pay no attention to politics.

A person in the left knows exactly who they’re voting for, and it’s never really been in question. What’s more, they can give you a very long list of the reasons they are voting for that person and–what’s more–all the terrible, horrible things about the leading contender that make him or her totally unfit for office and a threat to truth, justice, and the American Way. This is the kind of person who consumes a lot of news, but probably from a narrow range of sources, like DailyKos or RedState. They’re not bad people, but they high motivation tends to lead to an awful lot of research that is heavily skewed by confirmation bias.

A person on the right may also be unsure of how they’re going to cast their vote, but it’s not because they don’t know what’s going on. The problem is they do, and this knowledge has led them (as often as not) to fall right off the traditional left/right axis. I called myself a radical moderate when I was in high-school. At the time, it was mostly because I was on the far left but I wanted to sound cool. Later on in life I found myself near the peak of the bell-curve, a die-hard conservative with all the answers who was half-convinced that liberals were undermining the country. But then I went to graduate school to study economics (one of the areas where I was staunchly conservative) and lo and behold: things got complicated. I fell off the peak and I’ve been sliding down the slope ever since. And what do you know, but I found out recently that radical moderates are actually a thing. They even include some of my very favorite thinkers, like John McWhorter (cited above) and Jonathan Haidt (cited in a lot of my posts). I’ve come full circle, from know-nothing moderate to know-that-I-know-nothing radical moderate.

It’s kind of lonely and depressing over here, to be honest, and we don’t often find an awful lot to shout about. Which is why the conversation tends to be dedicated by peak-extremists who know just enough to be dangerous. About the only banner you’ll see us waving is the banner of epistemic humility. And really, how big of a parade can you expect to line up behind, “People probably don’t know as much as they think they do? (Including us!)”

But one thing that I can share with some conviction is this post, and the idea that–when it comes to ideas–fighting fire with fire just burns the whole house down. There is validity to the idea that things were better before Christopher Columbus showed up. There was a helpful lack of measles and small pox, for example. But blaming the transmission of those diseases (except in the rare cases when it was important) and the resulting humanitarian catastrophe on Columbus doesn’t make any sense. He did a lot of really evil things, but intentional germ warfare was not among them. Relying on it because the numbers are so big is lazy. There is also validity to the idea that Columbus lived in a different time. Many of the most compassionate Westerners were motivated not by a modern sense of equal rights but by a more feudal-tinged idea of noblesse oblige. De la Casa himself, for example, first suggested making things easier on Caribbean slaves by importing more African slaves before later deciding that all slavery was a bad idea. And if you fast-forward to the 19th century abolitionist movements, you’ll find plenty of what counts as racism in the 21st century among the abolitionists who were motivated (in some cases) by ideas of civilizing the savages. Racial politics are complicated enough in the 21st century alone, of course we can’t bring in perspectives from six centuries ago and expect all the good guys to neatly align on bullet point of focus-group vetted talking points!

So yes: I see validity to both sides of the fight. If your goal is to win in the short term, then the most useful thing to do is double-down on your strongest arguments and cherry-pick the other side’s weakest points. This is the strategy of two stupids making a smart, and it doesn’t work.

If your goal is to win in the long term, then you have to undergo a fundamental transformation of perspective.[ref]Do you see how I avoided the buzz-phrase “paradigm shift”?[/ref] The short-term model isn’t just short-term. It’s ego-centric. The fundamental conceit of the idea of winning is the idea of being right, as an individual. Your view is the correct one, and the idea is to have your idea colonize other people’s brains. It is unavoidably an ego-trip.

The long-term model isn’t just about the long-term. It’s also about seeing the whole that is more than the sum of the parts. In this view, the likeliest scenario is that nobody is right because, on any particular suitably complex question, we are like the world before Newton and the world before Einstein: waiting for a new solution no one has thought of. And, even if somebody does have the right solution to the problem we face now, that will almost certainly not be the right answer to the problem we will face tomorrow. In that case, it’s not about having the right ideas in the heads of the read people, it’s about having a culture and a society that is capable of supporting a robust ecosystem of idea-creation. The focus begins to shift away from the “I” and towards the “we.”

In this model, your job is not to be the one, singular, heroic Messiah who tells everyone the answer to their problem. Your job is to play your part in a larger collective. Maybe that means you should be the lone voice calling from the wilderness, the revolutionary prophet like Newton or Einstein. But more probably it means your job is to simply be one more ant carrying one more grain of sand to build the collective pile of human knowledge and maybe–through conversations with friends and family–shift the center of gravity infinitesimally in a better direction.

I’m not a relativist. I’m a staunch realist in the sense that I believe in an objective, underlying reality that is not dependent on social construction or individual interpretation. But I’m also a realist in the sense of acknowledging that the last living human being to have ever understood the entire domain of mathematics was Carl Friedrich Gauss and he died in 1865. No living person today understands all mathematical theory. And that’s just math. What about physics and history and chemistry and psychology? And that’s just human knowledge. What about the things nobody knows or has thought of yet? An individual is tiny, and so is their sphere of knowledge. The idea that the answers to really big questions fall within that itty-bitty radius seems correspondingly remote. In short: the truth is out there, but you probably don’t have it and you probably can’t find it. It may very well be, keeping this metaphor going, that the answer to some of our questions are too complex for any one person to hold in their brain, even if they could discover one.

I’m not giving up on truth. I am giving up on atomic individualism, on the idea that the end of our consideration with regards to truth is the question of how much of it we can fit into our individual skulls. That seems very small minded, if you’ll pardon the pun. Instead, I’m much more interested in ways in which individuals can do their part to contribute to building a society that may understand more than its constituent individuals do or (since that seems a bit speculative, even to me) at a minimum provides ample opportunity for individuals to create, express, and compare ideas in the hope of discovering something new.

Two stupids can’t make a smart. The oversimplification and prejudice necessary to play that strategy is not worth the cost. Winning debates is not the ultimate goal. We can aim for something higher, but we have to be willing to lay down our own egos in the process and contribute to something bigger.