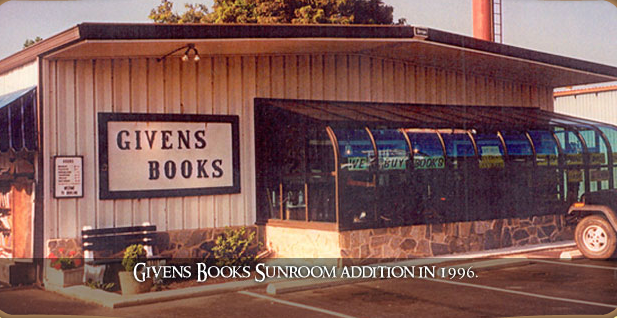

My grandfather started a bookstore in Lynchburg, VA long before I was born. Over years of family vacations, it became my favorite place. I spent countless hours of my childhood perusing the covers in the used sci-fi section. I took my favorites back into a break room where I could always find space on an old church pew and occasionally even an off-brand root beer in the mini fridge. My mind took to the stars as I read the old books with their tattered covers, leaving my body behind amid the clutter of American antiques and artifacts. Today, my uncle continues to run Givens Books in a new building down the street from the old one.[ref]The city bought it and demolished it for a road that they ended up never building.[/ref] Another uncle operates another Givens Books in another town. Books, you might say, are in my blood.

It’s not just buying and selling, of course. My grandfather was a history teacher before he was a book store proprietor, and his passion for history was life-long. He wrote several books about American and Mormon history like 500 Little-Known Facts in U.S. History

and In Old Nauvoo: Everyday Life in the City of Joseph

. Another book of his, a memoir of Christmas on the upstate New York farm where he lived as a child, was even picked up by Scribner: The Hired Man’s Christmas

. My father’s first published book was The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy

in 1997. He has been very busy since then, and my mother coauthored two of his most recent books (The God Who Weeps

and The Crucible of Doubt

). I also have at least one aunt who has written her own brilliant, albeit so far unpublished novels.[ref]I say “that I know of,” because I wouldn’t at all be surprised if some of my other aunts were writers, too.[/ref]

And when my family isn’t writing books they are, of course, reading them. Lots and lots and lots of books. But at this point I have to specify that the Givens clan, by and large, reads serious literature. And, on that score, I’ve been a bit of a disappointment to everyone.

Other than the assigned books for school, I have always read pretty much exclusively fantasy and science fiction. From Brian Jacques to J. R. R. Tolkien

, and from Alan Dean Foster

to Orson Scott Card

, I wanted books with magic and spaceships.[ref]Especially spaceships. I fast-forwarded to the space combat scenes in Return of the Jedi on our VCR copy so many times that I broke it and had to patch it with tape. Which totally worked, by the way.[/ref]

This was probably fine when I was just starting to read on my own in elementary school. I went through dozens of Hardy Boys and a lot of Tom Swift, Jr. (which I liked more) and several series of similar kid mystery books from England. Even in middle school it probably wasn’t too alarming. Who can say no to a little Susan Cooper

? Others, like Madeleine L’Engle

, were probably supposed to be the gateway drugs into more serious literature. But for me, they weren’t, and by the time I was in high school this was clearly something of let-down for all concerned.

The most pristine example of this dynamic was when my cousin (just a couple of years older than me) had his copy of Piers Plowman along with him at a family gathering. Piers Plowman is “a Middle English allegorical narrative poem… written in unrhymed alliterative verse…considered by many critics to be one of the greatest works of English literature of the Middle Ages.” At more or less the exact same time, I was reading Timothy Zahn’s Thrawn trilogy, which is “a series of best-selling science fiction novels…set in the Star Wars galaxy approximately five years after the events depicted in Return of the Jedi.” After all, they had spaceships.[ref]Actually, I might have been re-reading them.[/ref]

My parents were–and are–great. I don’t recall a single lecture about this, let alone any ultimatums or demands. When my dad realized how hooked I was on sci-fi, the best he could do was ask his colleagues in the English department to recommend the best sci-fi had to offer. This is how I got into Isaac Asimov‘s Foundation series[ref]Which, while a classic, is just not really well-written. I liked I, Robot a lot more when I found that on my own a little later.[/ref] and also Philip José Farmer. Unfortunately, no one recommended Ray Bradbury or Philip K. Dick

or Ursula K. Le Guin

at the time, which really goes to show you that English professors are probably not the best crowd to get sci-fi advice from.

The point, however, is that even though my father did his best not to look at me while my cousin was expressing just how fascinated he was by Pier and his damnable plow, I knew the comparison was too obvious to be missed.

To this day, my uncles and aunts ask me what I’m reading whenever we meet up. This question is both necessary and–in most cases–sufficient for all conversation at a Givens clan gathering. I reply, as often as not, that I’ve just read (e.g.) Jim Butcher’s newest novel and it was fantastic. They never recognize the books, and so they ask for more info with that voracious glint in their eyes that a Givens gets whenever they detect the proximity of satisfying literary prey. But, as soon as they hear “fantasy” or “science fiction,” they remember who they are talking to. Instead of a thick, juicy, literary steak I am talking about bubblegum and breath mints. Interest in literature wanes as they consider me with concern. It’s as though they asked me how work was going, and I told them that it was going pretty well: my boss had given me a promotion now that I knew how to fit the shapes into the correct slots on the first try most of the time.

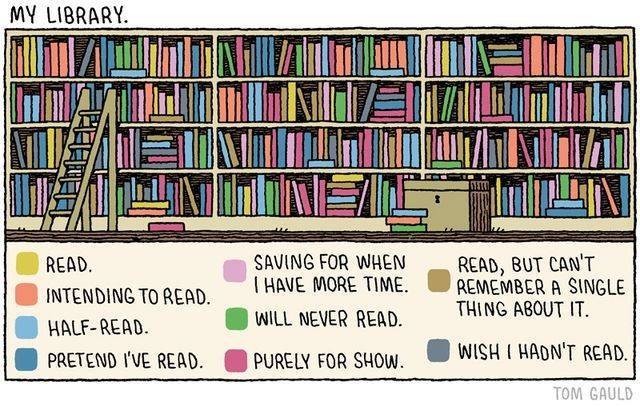

The problem is, that somewhere along the way I picked up the idea that you were the kind of person who read serious literature or you were the kind of person who did not. You know, it’s the old:

When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me.

I felt like I had to choose either-or, and I had some pretty compelling reasons not to go with the serious stuff. First, although I enjoyed some of the literature I got assigned to read in high school and college, the ones that I didn’t like I really didn’t like. Case in point: Siddhartha by Herman Hesse. Oh man, I loathed that book with all the pure and fiery indignation of adolescence. The idea that spirituality requires detachment from ordinary life was (and still is) repulsive to me. If the sacred and the holy cannot survive close proximity to real life then what good are they? Maybe at 33 I’d be less judgmental than I was at 14, but my idea of monolithic categories meant that a couple of bad experiences poisoned the well. If the powers that be put Siddhartha in the same category as The Sheltering Sky, I felt I had to take or leave them together.

I loved The Sheltering Sky, by the way, even though it wasn’t a fun book. I also loved Hemingway, and For Whom the Bell Tolls was probably the one (and only) serious book I read voluntarily as a teenager. Not only had books like Siddhartha sort of peed in the pool, however, but there was also the way that serious literature was read. In college, we had a handbook in one class full of the different literary approaches. You could choose from Marxism, feminism, or deconstructionism. The same authority that said “these are the books to read,” was also telling me “and this is how you read them.” No, thanks.

It’s not that I’m averse to analyzing what I read. Far from it, I can almost never turn off the analytic side of my mind, and most of the time I enjoy it. Probing and critiquing is how I enjoy most of what I enjoy. It’s second nature. The two things that bugged me about the way literary analysis was taught in high school, however, were first that it was so dogmatic and second that it was pathetic to have a bunch of 14-year olds pontificating about books that were way, way outside our capacity to really understand.

As for the dogma: I think that’s kind of self-explanatory. It’s no secret that certain kinds of views are allowed in the humanities, and other views not so much. It’s not that I was so concerned about seeing conservatism recognized, but I just wanted to be able to be freely curious. At the extreme end of the spectrum, I signed up for an elective women in literature class my senior year of high school. I just wanted to understand different viewpoints. I expected to be one of the only guys in the class, but what I didn’t expect was the wall of hostility that greeted me every day. I wasn’t trying to debate anyone. In fact, I wasn’t even trying to ask questions or influence the conversation: I just wanted to sit and listen. But I soon realized that my presence was an unwelcome imposition, so I dropped the class. Even when the examples were not quite as flagrant the message was always universal: only certain kinds of perspectives and certain kinds of people were actually welcome.

As for the analysis: I don’t think that at 33 I’ve arrived at some pinnacle of understanding that I didn’t have when I was still in school at 14 or 18 or 22. But the greater life experiences and the historical and philosophical context make these books mean much, much more to me than they possibly could have then. Going back to The Sheltering Sky for a minute: that book came to life for me all over again when I took a class on existentialism in college. Even though I’d already liked it, my appreciation grew dramatically when I was able to put it in context. The lesson is simple: as a teenager the emphasis should have been more on understanding and less on critiquing the great works. Even most teenagers know that they don’t have anything special or unique to say about books that have been studied by scholars for decades or centuries, so the activity of forcing everyone to pontificate resulted in contrived, hackneyed, embarrassing experiences that undercut the possibility of approaching literature more as student and less as judge or critic.

So, given the political dogma, the pretentious critiques, and the boring books that I thought I’d have to take along with the good ones: I said no, thanks to serious literature. When school was out and I could read whatever I wanted, I glutted myself on fantasy and sci-fi to my heart’s content. But then a funny thing happened. After a few years of this, the books started to lose their taste. I found I’d lost the ability to lose myself in the stories.

My literary Peter Pan syndrome kept me deathly opposed to abandoning my sci-fi for classics, but I started cautiously moving out towards literary sci fi. I read more Vonnegut, more Bradbury, and more Dick. They were all great. Then I turned to more recent literary sci fi with books like Never Let Me Go

and The Handmaid’s Tale

. I loved them as well, so I kept exploring further. I was still dedicated to staying conspicuously away from outright serious literature, so instead I experimented with some classic American noir: The Big Sleep

and Promised Land

.[ref]Not really noir, since it was set in the 1970s, but definitely from the same tradition.[/ref] And I loved all of them, too.

Next thing you know, I started asking my family for the books they liked to read, and before you knew it I’d read Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead and Wallace Stegner’s Angle of Repose

and both of them blew me away. Most recently, I just finished Joseph Conrad‘s The Secret Agent

and finally the dam burst. I mean, Joseph Conrad is as serious as you can get, really. His work is over a century old and I had, of course, read Heart of Darkness in high school. I didn’t get it then, but I got The Secret Agent now. And it wasn’t any of the nonsensical analytic hogwash that I’d rejected in school. It was the sheer power of his writing and, above all, the strength of his amazing metaphors and similes. Here was writing that touched my soul. Here was writing that lived up to Joseph Conrad’s ambition to “by the power of the written word… make you hear, … make you feel… [and] before all, to make you see. That – and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, consolation, fear, charm – all you demand – and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask.”

Not only had I finally fallen in love with some of the literature that I’d eschewed as a kid, but I also couldn’t help but see the obvious parallels between a writer like Conrad (serious literature) and a writer like Ray Bradbury (sci-fi). They are not very similar, all things considered, but they both have a gift for some of the most novel, evocative similes I’ve ever read, doled out with such breathtaking profligacy that I’m left in awe.

It also helped, by the way, that I read a few books I hated. Camus’ The Stranger did absolutely nothing for me, despite the fact that I had loved The Plague. And don’t get me started on Dorris Lessing‘s sci-fi catastrophe.

What really got through to me the most, however, was that at the same time that I was reading serious literature and loving it, I was finding that popular sci-fi and fantasy were starting to resonate with me again for the first time in years. During the same years where I discovered my love of Stegner and Conrad I was also devouring

Brandon Sanderon’s epic fantasy tomes and re-affirming Jim Butcher’s place as my very favorite living author

.

Now, this may very well be obvious to all of you, but it’s been a revelation to me. Entertainment is part of our identity. Or at least that’s how people usually think of it. In high school and college–when we’re all building our identities–the kind of music that you listen to is automatically connected to the clothes you wear and the friends you have. Turns out, the main reason for that is insecurity and inexperience, and that there’s actually no good reason why you shouldn’t alternate between Renaissance religious chants and screamo. Or, back on the topic of literature, between Fyodor Dostoevsky and John Ringo

.

I’m not trying to equate the two. I have pretty strong opinions about who is better at the sheer craft of writing as an art form, and it’s going to be Dostoevsky over Ringo (and on down the line in favor of serious literature in most cases).[ref]I sort of doubt John Ringo would contest that.[/ref] But there are lots of different kinds of beauty in the world. The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is one and riding on a roller coaster is another. Which is better? Do you want to have to pick just one? Because I don’t. I love going on very long runs (12 miles is my max so far) with all the pain and the sweat and the weakness and the satisfaction that comes with it. I love sleeping in when the temperature is just perfect and the blankets are at optimal coziness and there’s nothing that you absolutely have to do just yet. Is one of these a better way to enjoy the sheer physical sense of being a mortal, living, physical creature than the other? I don’t care to debate, because I choose both.[ref]Although not at the same time, clearly.[/ref]

Life is dark and disappointing enough as it is. I read a quote somewhere that said the secret of life is learning how to let yourself down gently, and it has always stuck with me. The most likely scenario is that none of your dreams are going to come true. Even if they do: they won’t be as beautiful as you imagined. That might sound depressing, but it’s reality. I think that if we could see, at age 14 or 18, all the pain and heartache that lies in store for us we would go literally insane with fear and horror. But there’s also beauty. And the really, really strange thing about being human is that the pain and the joy never seem to cancel out. The positive and negative just keeping adding up. The books are never balanced. If we could see all the beauty and happiness that life has in store for us, we’d be just as quickly reduced to a blubbering mess.

I have a depressing view of human existence, sure, but I have a romantic one, too. Every year I discover new bands, new songs, new books, new movies, new places, new ideas, new images, new people that I quickly come to love so much I can’t believe that I ever got along without them. What else is out there today, crafted by some unknown (to me) artist that will bring a light to those dark tomorrows? I have no idea, but since life has brought me enough of disappointment and never too much joy I am determined not to wall off any beautiful possibilities.

A while back someone asked me why this quote from Kurt Vonnegut means so much to me:

I am honorary president of the American Humanist Association, having succeeded the late, great, spectacularly prolific writer and scientist, Dr. Isaac Asimov in that essentially functionless capacity. At an A.H.A. memorial service for my predecessor I said, “Isaac is up in Heaven now.” That was the funniest thing I could have said to an audience of humanists. It rolled them in the aisles. Mirth! Several minutes had to pass before something resembling solemnity could be restored. I made that joke, of course, before my first near-death experience — the accidental one.

So when my own time comes to join the choir invisible or whatever, God forbid, I hope someone will say, “He’s up in Heaven now.” Who really knows? I could have dreamed all this. My epitaph in any case? “Everything was beautiful. Nothing hurt.” I will have gotten off so light, whatever the heck it is that was going on.

I love this quote–it brings me near to tears whenever I read it–because it is a lie, but it’s a beautiful one. It’s the same lie I tell myself so that I can keep going. It’s the same lie I hope my kids believe. It’s the same lie that–despite calling it a lie–I hope turns out to be true. The lie, and as long as we see only with mortal eyes it will remain an earthly lie, is that one day we will see something that makes it all beautiful. That one day we will feel something that makes all the hurt go away. That one day we will understand something that quiets the confusion we carry with us through our lives every single damn day. That one day we will be together with the people we have missed so much. That even though I can never go back to my grandfather’s bookstore again, one day I’ll be able to see him again.

Until that great day of hope, we’re stuck here in the darkness. But we can still see lights. There are tiny sparks that whisper to us of the promise of dawn. I believe one day the lie will become truth. I believe one day the sun will rise. Until then? I want to gather to myself every one of these flickers of light that I can. While I live, there will never be enough beauty. And I want it all.