I’ve written about my criticisms of minimum wage a couple of times already. (Walker has weighed in as well.) Here’s a good article, posted by Michigan economist Miles Kimball but quoting fellow professor Jeff Smith, on reasons why Jeff Smith refuses to sign a petition supporting a raise in the minimum wage. His concerns are:

1. It is poorly targeted relative to alternative policies such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). And, yes, I am familiar with the argument that the minimum wage and the EITC are complements; what is thin on the ground, so far as I am aware, is evidence of the empirical importance of this argument.

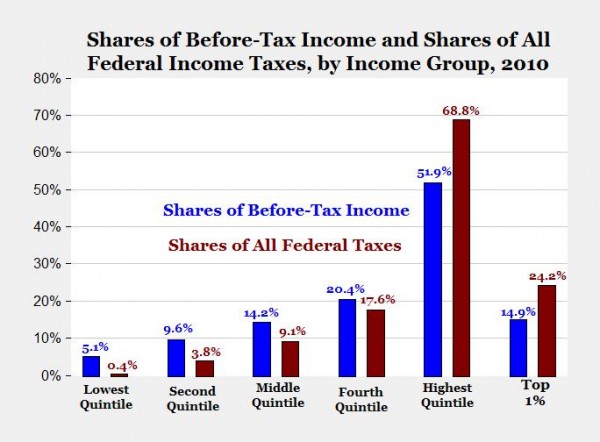

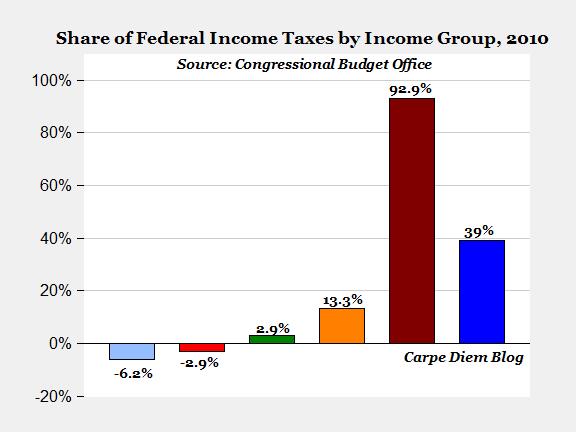

2. As pointed out recently by Greg Mankiw, it distributes the costs of the increased minimum wage in a less attractive way than alternative policies such as the EITC, which implicitly come out of general tax revenue.

3. Most importantly, raising the minimum wage fails to address the underlying issue, which is that many workers do not bring very much in the way of skills to the labor market. Rather than having a discussion about raising the minimum wage, we should be having a discussion about how to decrease the number of minimum wage workers by increasing skills at the low-skill end of the labor market. This would, of course, mean challenging important interest groups. It is also a bigger challenge more broadly because it is less obvious how to do it. But that is the discussion we should be having because that is the one that will really help the poor in the long run, in contrast to a policy that feels good in the short run but only speeds the pace of capital-labor substitution in the long run.

None of these arguments are novel, and I’ve cited all of them in the past, but they are worth repeating. Minimum wage: the best you can say is that it’s a really inept and obsolete policy.