I don’t speak out on transgender issues much, for a bunch of reasons. I’m a cis woman, and I don’t really have any idea what it would be like to be trans. I have only a few friends who are trans (that I know of) to even talk to about it. Also, I’m concerned about multiple factors in the debates around this issue, and I haven’t figured out how heavily I weigh each factor and thus what my position is.

I’m irritated at some of my leftist friends for being unwilling or incapable of considering that anyone could have concerns, questions, or objections about trans issues and policies based on anything other than bigotry. I find that ridiculously simplistic and also really counterproductive if the goal is to get more people to understand and accept people who are trans.

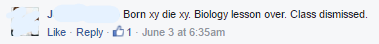

I’m also irritated with some of my right-wing friends for depicting these issues as nothing more than a cavalier preference chosen for trivial reasons, as if people just wake up one day and “feel like” being a different gender. In particular I get annoyed at people for greatly oversimplifying biology. My writing today was inspired by a random comment I saw on a friend’s post:

Whatever your thoughts on the moral, social, political, and legal implications of trans issues, the statement above (and others similar to it) are overgeneralizations. And, as with most generalizations, they won’t hurt most people because most of the time they’ll be true. But they can cause problems for the exceptions, and I think we should be mindful of that.

So, continuing the biology lesson:

(Typically) our mother’s eggs each contain an X chromosome and our father’s sperm each contain either an X chromosome or a Y chromosome. When egg and sperm meet, the sperm’s chromosome determines the sex of the resulting child. A person with both an X and Y chromosome is male, and a person with two X chromosomes is female. Generally.

However, when we talk about someone being “biologically female” or “biologically male,” there are multiple factors to consider. The ones we talk about most are:

- Chromosomes (female = XX, male = XY)

- Gonads (female = ovaries, male = testes)

- External genitalia (female = vagina, male = penis)

Most people either possess all three of the female traits or all three of the male traits. However some people instead have some combination of male and female traits. For example, there are multiple ways an XY person could lack specifically male genitalia (or an XX person could lack specifically female genitalia). Mayo Clinic has a good summary here:

- A lack or deficiency of male hormones in a genetic male fetus can cause ambiguous genitalia, while exposure to male hormones during development results in ambiguous genitalia in a genetic female.

- Mutations in certain genes can influence fetal sex development and cause ambiguous genitalia.

- Chromosomal abnormalities, such as a missing sex chromosome or an extra one, also can cause ambiguous genitalia.

For example, Swyer syndrome is a condition in which an XY person develops female reproductive organs. There are several different gene mutations that have been associated with the phenomenon. People with Swyer syndrome often grow up with the female gender identity and keep that identity throughout their lives.

As another example, a condition called 5-alpha reductase deficiency (5aR deficiency) means XY people don’t produce enough of a certain hormone to form male external sex organs. They typically grow up with the female gender identity, however they may adopt a male gender role later in life.

There are other conditions that can have these kinds of “misalignment” effects. As far as I know, none of these conditions are very common. Swyer syndrome is thought to happen in 1 out of 80,000 people, and 5aR deficiency is rare enough it’s unclear how many people have it.

However I don’t think that because these issues are rare, we should act as if they don’t exist. I imagine it can be very difficult for people with these conditions to process both how they view themselves and how society views them. Insisting there is nothing more to sex or gender than either our chromosomes or our genitalia is untrue and, in some cases, I think it’s unkind.

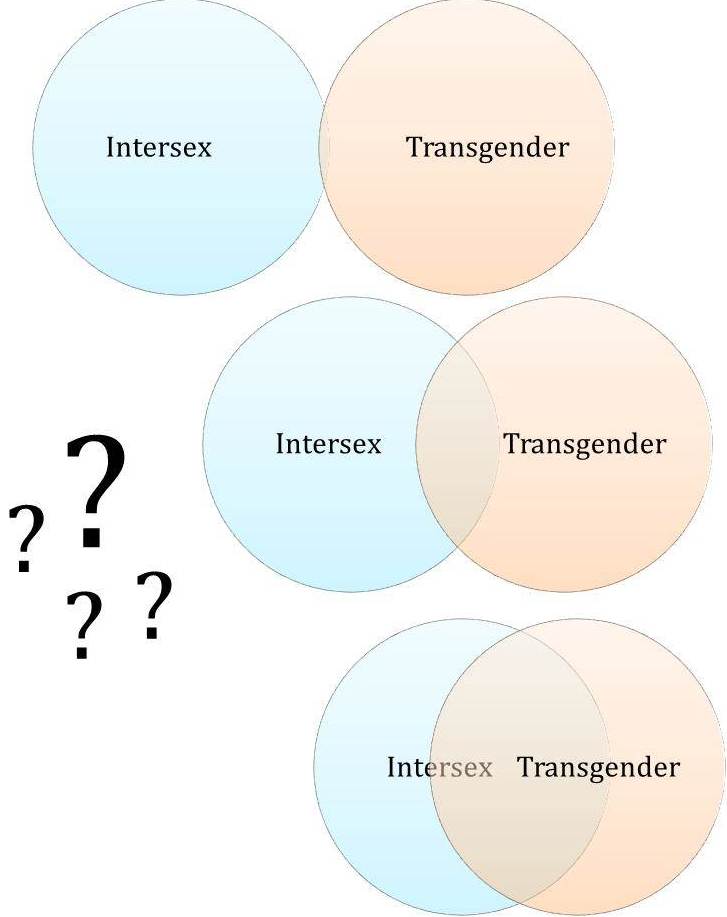

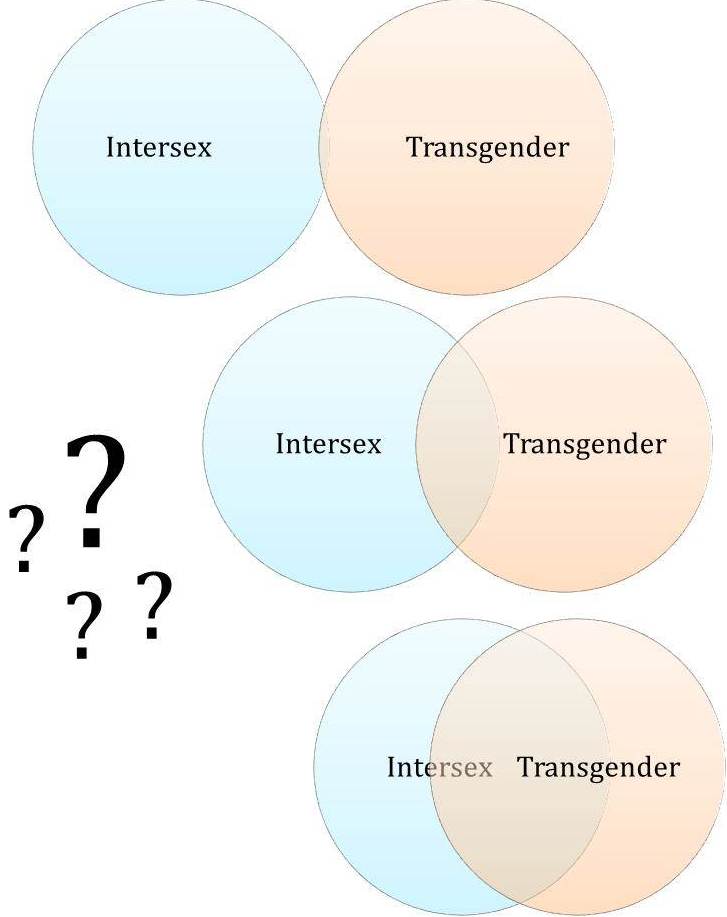

That being said, intersex issues like the ones I mentioned don’t cover the whole scope of trans issues. In fact if there was a Venn Diagram of the two, I’m unclear on how much it would cross over.

Intersex issues occur when a person’s biological traits aren’t all either male or female. Trans issues occur when a person identifies as a gender other than the gender normally associated with their biological traits. A trans man could be intersex: he could have external female genitalia but testes and XY chromosomes (intersex) and identify as male (trans). But a trans man isn’t necessarily intersex: he could have external female genitalia, ovaries, and XX chromosomes (not intersex) and identify as male (trans).

And likewise, an intersex person isn’t necessarily trans. Many intersex people don’t have gender identity issues; they spend their entire lives identifying as one gender and having society recognize them as that gender and it isn’t something they struggle with. In fact, some intersex people really object to having intersex issues conflated with trans issues.

So there is some overlap between intersex and trans people, but the extent of the overlap is unclear. And if we assume it’s 1:1 we ignore all the intersex and trans people for whom the overlap doesn’t apply.

Not only that, but if we assume it’s 1:1 we oversimplify the cultural discussion. Just as it’s too black and white to act as if biological sex is always straightforward, it’s too black and white to act as if trans issues are always, much less solely, based on biological “misalignments.” I object to both those oversimplifications. We should be able to make our points and explore our arguments without having to dismiss inconvenient truths.

Positive psychology has really taken off over the years and psychologist Martin Seligman’s Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being is an excellent summary of its findings. Seligman identifies several elements of well-being, including (1) happiness and life satisfaction, (2) engagement, (3) meaning, and (4) accomplishment. A huge factor in all of this is positive relationships. As Seligman notes, “When asked what, in two words or fewer, positive psychology is about, Christopher Peterson, one of its founders, said, ‘Other people‘” (pg. 51). Throughout the book Seligman provides exercises that can help boost positive emotions. He also discusses a couple case studies of positive psychology interventions in both schools and the military, both of which improved the well-being of students and soldiers alike. Finally, he delves into the power of grit, optimism, post-traumatic growth, and values vs. ethics. Overall, an enlightening read.

Positive psychology has really taken off over the years and psychologist Martin Seligman’s Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being is an excellent summary of its findings. Seligman identifies several elements of well-being, including (1) happiness and life satisfaction, (2) engagement, (3) meaning, and (4) accomplishment. A huge factor in all of this is positive relationships. As Seligman notes, “When asked what, in two words or fewer, positive psychology is about, Christopher Peterson, one of its founders, said, ‘Other people‘” (pg. 51). Throughout the book Seligman provides exercises that can help boost positive emotions. He also discusses a couple case studies of positive psychology interventions in both schools and the military, both of which improved the well-being of students and soldiers alike. Finally, he delves into the power of grit, optimism, post-traumatic growth, and values vs. ethics. Overall, an enlightening read.

A

A