Theologian David Bentley Hart has an interesting piece in The New York Times titled “Are Christians Supposed to Be Communists?” Hart writes:

If the communism of the apostolic church is a secret, it is a startlingly open one. Vaguer terms like “communalist” or “communitarian” might make the facts sound more palatable but cannot change them. The New Testament’s Book of Acts tells us that in Jerusalem the first converts to the proclamation of the risen Christ affirmed their new faith by living in a single dwelling, selling their fixed holdings, redistributing wealth “as each needed” and owning all possessions communally. This was, after all, a pattern Jesus himself had established: “Each of you who does not give up all he possesses is incapable of being my disciple” (Luke 14:33).

If the communism of the apostolic church is a secret, it is a startlingly open one. Vaguer terms like “communalist” or “communitarian” might make the facts sound more palatable but cannot change them. The New Testament’s Book of Acts tells us that in Jerusalem the first converts to the proclamation of the risen Christ affirmed their new faith by living in a single dwelling, selling their fixed holdings, redistributing wealth “as each needed” and owning all possessions communally. This was, after all, a pattern Jesus himself had established: “Each of you who does not give up all he possesses is incapable of being my disciple” (Luke 14:33).

This was always something of a scandal for the Christians of later ages, at least those who bothered to notice it. And today in America, with its bizarre piety of free enterprise and private wealth, it is almost unimaginable that anyone would adopt so seditious an attitude.

While Christianity “was not a political movement in the modern sense,” it “was a kind of polity, and the form of life it assumed was not merely a practical strategy for survival, but rather the embodiment of its highest spiritual ideals. Its “communism” was hardly incidental to the faith.” He points out that “the New Testament’s condemnations of personal wealth are fairly unremitting and remarkably stark,” going on to cite Matt. 6:19-20, Luke 6:24-25, and James 5:1-6. “While there are always clergy members and theologians swift to assure us that the New Testament condemns not wealth but its abuse, not a single verse (unless subjected to absurdly forced readings) confirm the claim.”

The early Christians saw “themselves as transient tenants of a rapidly vanishing world, refugees passing lightly through a history not their own.” Many fourth and fifth-century theologians “felt free to denounce private wealth as a form of theft and stored riches as plunder seized from the poor. The great John Chrysostom frequently issued pronouncements on wealth and poverty that make Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin sound like timid conservatives.”

He concludes,

No society as a whole will ever found itself upon the rejection of society’s chief mechanism: property. And all great religions achieve historical success by gradually moderating their most extreme demands. So it is not possible to extract a simple moral from the early church’s radicalism.

But for those of us for whom the New Testament is not merely a record of the past but a challenge to the present, it is occasionally worth asking ourselves whether the distance separating the Christianity of the apostolic age from the far more comfortable Christianities of later centuries–and especially those of the developed world today–is more than one merely of time and circumstance.

While I think Hart is correct about the radicalism of the early Christian church, he only briefly mentions a major driving force behind their radicalism: they saw “themselves as transient tenants of a rapidly vanishing world.” The early Church was more-or-less a Jewish apocalyptic movement. Believing the world is going to end soon tends to produce radical practices.[ref]The same is true for early Mormonism.[/ref] And while the Book of Mormon may be a little more nuanced in regards to wealth,[ref]See Jacob 2:17-19.[/ref] it’s not by much.[ref]For example, see my essay in As Iron Sharpens Iron: Listening to the Various Voices of Scripture.[/ref] So what does our economic world look like today compared to that of 1st-century Palestine? Harvard historian Niall Ferguson writes,

Despite our deeply rooted prejudices against ‘filthy lucre’…money is the root of most progress…[T]he ascent of money has been essential to the ascent of man. Far from being the work of mere leeches intent on sucking the life’s blood out of indebted families or gambling with the savings of widows and orphans, financial innovation has been an indispensable factor in man’s advance from wretched subsistence to the giddy heights of material prosperity that so many people know today. The evolution of credit and debt was as important as any technological innovation in the rise of civilization, from ancient Babylon to present-day Hong Kong. Banks and the bond market provided the material basis for the splendours of the Italian Renaissance. Corporate finance was the indispensable foundation of both the Dutch and British empires, just as the triumph of the United States in the twentieth century was inseparable from advances in insurance, mortgage finance and consumer credit.[ref]The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, pgs. 2-3.[/ref]

What was Jesus’ economic world like? Religious studies scholar Philip Harland explains,

First, the ancient economy of Palestine was an underdeveloped, agrarian economy based primarily on the production of food through subsistence-level farming by the peasantry. The peasantry, through taxation and rents, supported the continuance of a social-economic structure characterized by asymmetrical distribution of wealth in favor of the elite, a small fraction of the population. Peasants made up the vast majority of the population (over 90 percent…)…[W}ealth in the form of rents, taxes, and tithes flowed toward urban centers, especially Jerusalem (and the Temple), and was redistributed for ends other than meeting the needs of the peasantry, the main producers. The city’s relation to the countryside in such an economy, then, would be parasitic, according to this view (pg. 515).

Bruce Longenecker of Baylor University provides the following estimates about Greco-Roman urban life (pg. 264):

- 3% of the population was wealthy (e.g., imperial to municipal elites).

- 17% had a moderate surplus (something like a middle class).

- 80% were just above, just at, or just below the subsistence level.

According to economist Edd Noell,

The direction of income to particular favored groups shaped attitudes toward wealth accumulation in first-century Palestine. Indeed, in the New Testament era, it can be argued that the rich or wealthy “as a rule meant [those who were] ‘avaricious, greedy’” (Malina 1987, 355), rather than those who held a specific level of net worth. The wealthy obtained their standing by extractive or redistributive actions; resentment was generated toward these individuals who “impose tributes, extract agricultural goods, and remove them for ends other than peasants want” (Hanson and Oakman 1998, 113). This notion dovetailed with the notion that participation in the economy was a zero-sum game. Schneider asserts that in Palestine “the rich were very often (though not always) people who had made a bargain with the devil Rome”; the gouging of the typical farmer through overpayment of taxes and other means suggests that “we will comprehend the New Testament better if we understand that financial advantage in Israel often implied direct involvement with political evil and injustice” (2002, 121). Hanson and Oakman add that “rich and powerful people could be looked upon as robbers and thieves as much as benefactors” (1998, 111) (pgs. 100-101).

Interestingly enough, this seems to fit the distinction between extractive and inclusive institutions outlined by Acemoglu and Robinson in their book Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Power. Reviewing their book, philosopher Bas van der Vossen comments,

Inclusive institutions empower people across society, and thus tend to benefit all. Extractive institutions empower only some, and thus tend to benefit only small groups of people…On the economic side, inclusive institutions secure people’s rights to private property, including private property rights over productive resources, and allow these to be held broadly across society. These allow societies to experience the kinds of specialization, exchange, investment, and innovation that increase productivity…Extractive economic institutions, by contrast, are those that limit or altogether prevent the ability of people across society to individually own private and productive property, engage in commercial and profit-seeking activities, and enjoy the fruits of their investments and innovations. Such institutions stifle productivity.

…It is important to stress here that Acemoglu and Robinson do not deny that economic growth can occur under extractive institutions. Such ‘extractive growth’ can happen either because of strong policies of state investment in highly productive sectors of the economy (as in Caribbean slave-economies from the sixteenth until the eighteenth century, or the Soviet Union until the 1970s), or because pockets of inclusive economic institutions exist in a larger extractive setting (as in South Korea in the 1960s and 70s).

But such growth never lasts. Extractive economies sooner or later stop growing, or collapse altogether, due to a lack of innovation, state incompetence, conflict and corruption, or the withering away of whatever small inclusive parts may have existed. Only inclusive economic institutions, protected by inclusive political institutions, can offer the kinds of sustained investment, innovation, flexibility, and creative destruction that create a continued path of growth and prosperity (pgs. 68-69).

But here’s the clincher:

The philosophical literature on global justice and ethics contains disturbingly many theories that proceed in ways that are strangely disconnected from the best empirical studies about poverty and prosperity. Sometimes the empirical insights are simply set aside or even ignored. And even those who do engage with them or focus on the role of institutions frequently fail to see the forest for the trees. Hence, we read proposals for new global institutions (ignoring that the quality of domestic institutions is at least as important), we see arguments for extensive redistribution (ignoring that such policies will be counter-productive if not accompanied by institutional changes in developing countries), and so on.

The most important lesson that Why Nations Fail (and other works like it) contains for philosophers working on global justice is this: getting our economic institutions right is just as important as getting our political institutions right. And the evidence strongly indicates that this means endorsing market societies, with strong property rights over private and productive resources and economic freedom for all.

It is hard to say why these facts have been ignored or denied by philosophers for so long. Perhaps the hostility toward inclusive economic institutions is that they are seen as contestable parts of neoliberal, libertarian, or other free market perspectives. But this is to miss the point. Among the most exemplary inclusive countries are European welfare states like Denmark, Sweden, and Germany. Strong property rights and robust economic freedom are compatible with a variety of redistributive policies. Why Nations Fail is far from a libertarian manifesto. And if even those countries are too much market-oriented for our taste, well, I propose we get over it. There is simply too much at stake (pg. 74).

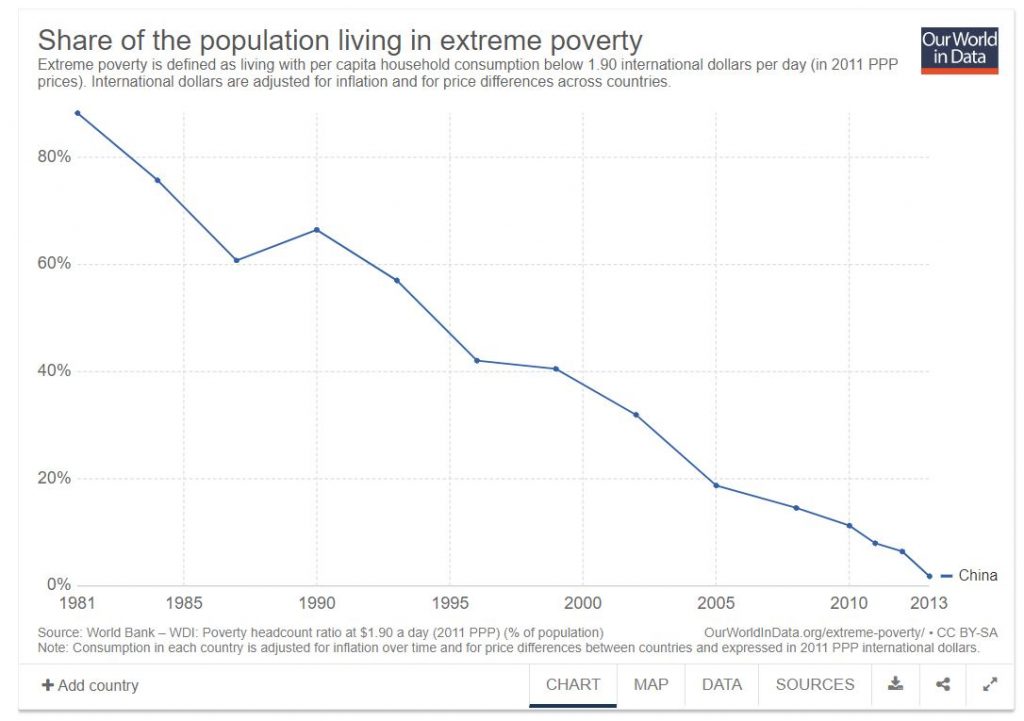

Now what’s my point? Do I think Hart is wrong? No. Far from it. I think he’s absolutely right about the text and the early Christians. However, the text has a specific historical, economic, and socioreligious context. And this context explains the condemnations of wealth and the lack of concern for material prosperity.[ref]Oddly enough, some sociological and textual evidence suggests that even Jesus and his closest disciples were financially well-off.[/ref] But in a world that hasn’t ended, how are modern Christians supposed to apply these alien and radical teachings? What about the Bible’s concern for the poor?[ref]The Law of Moses had rules in place to make sure the poor were provided for (Ex. 21:2-6; 23:10-11; 22:25-27; Lev. 19:9-10; 25:3-7, 25-27; Deut. 14:28-29; 15:12-15; 24:19-21; 26:12-13). The prophets consistently reminded Israel and its rulers of their obligations to the poor (Isa. 10:1-4; Amos 2:6-7; 4:1; Ezek. 18). Oppressors of the poor were considered wicked (Ps. 37:14; Prov. 14:31) and God himself would provide and protect the poor (Isa. 41:17; Ps. 140:12). The prophetic concern for the economically disadvantaged continued with the ministry of Jesus, who declared his mission to involve “preach[ing] the gospel to the poor” (Luke 4:18). Christ taught that to feed the hungry and thirsty, clothe the naked, visit the sick and imprisoned, and host the stranger—“the least of these”—was to do so unto him (Matt. 25:35-40). In Jesus’ view, the one thing the rich man lacked was to “sell whatsoever thou hast, and give to the poor…and come, take up the cross, and follow me” (Mark 10:21). The Christian charge to care for the poor continued in the early Christian communities, with Paul seeking a collection for the poor of the Jerusalem church (Gal. 2:1-10; 1 Cor. 16:1-4; Rom. 15:25-27). See also Michael D. Coogan, “Poor,” in The Oxford Companion to the Bible, ed. Bruce M. Metzger, Michael D. Coogan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).[/ref] Does it matter that the poor in developed nations are richer than the rich in Jesus’ time and even today are some of the wealthiest people on the planet?[ref]Try playing around with different income adjustments at Giving What We Can. If you’re making $10,000 annually as a single person (a little over $2,000 below the 2017 U.S. poverty threshold), you’re still in the richest 20% of the world population. If you’re making $20,000 as a couple with two kids (over $4,000 below the 2017 U.S. poverty threshold), you’re still in the richest 20% of the world population. And this is just income. We’re not even touching on the innovations and technological advances that make life materially better today.[/ref] Does it matter that global markets and inclusive economic institutions have reduced extreme poverty to its lowest levels in human history?

Surely it matters. It has to. I can’t fathom that it wouldn’t. But this makes me ask a question that–as a committed Christian–bothers me a great deal: how relevant is the New Testament for today regarding practical matters? If the world hasn’t and isn’t ending any time soon, does it make much sense to “not worry, saying, ‘What will we eat?’ or ‘What will we drink?’ or ‘What will we wear?’” (Matt. 6:31, NRSV)? If the Kingdom of God is at hand, then financial concerns and the like are certainly trivial. But since the Kingdom is about 2,000 years late, what are we supposed to do? Concerns for and alleviation of the poor among early Christians must have been thought of as a relatively short-term deal, seeing that social and economic justice would be fully achieved in the soon-to-come Kingdom of God. But since we appear to be in for the long haul, do Jesus’ teachings need to be recontextualized? Do they need to be–to borrow Nephi’s words–“liken[ed]…unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning” (1 Ne. 19:23)? Or have we, as Hart suggests, truly strayed from the real intent of Christ’s words?

I’m not exactly sure. It’s a paradox I live with as one who is supposed to be a “stranger and pilgrim” (1 Peter 2:11) in a world that is getting better by virtually every empirical measure.[ref]Granted, I belong to a church that believes in continuing revelation, which somewhat eases the tension. But Mormonism is full of its own paradoxes.[/ref]

Maybe the paradox is the point. But it sure sucks at times.

The [alt-right] is disorganized and mostly anonymous, making it difficult to study systematically, and until recently its definition was up for grabs. Throughout 2016, the term “alt-right” was often applied to a much broader group than it is today; at times, it seemed to refer to the entirety of Trump’s right-wing populist base. Since the U.S. presidential election, however, the alt-right’s nature has become clearer: it is a white nationalist movement that focuses on white identity politics and downplays most other issues. As the alt-right’s views became better known, many people who had flirted with the movement

The [alt-right] is disorganized and mostly anonymous, making it difficult to study systematically, and until recently its definition was up for grabs. Throughout 2016, the term “alt-right” was often applied to a much broader group than it is today; at times, it seemed to refer to the entirety of Trump’s right-wing populist base. Since the U.S. presidential election, however, the alt-right’s nature has become clearer: it is a white nationalist movement that focuses on white identity politics and downplays most other issues. As the alt-right’s views became better known, many people who had flirted with the movement

…Consumer demand is shockingly low overall: American spend 0.2% of their income on all reading materials, barely more than $100 per family per year. Americans used to spend more on reading, but never spent much: Back in 1990, well before the rise of the web, reading absorbed 0.5% of the family budget. Today’s Americans spend about four times as much on tobacco and five times as much on alcohol as they do on reading. Within this small pond, high culture is no big fish. Here are three rankings of the bestselling English-language fiction of all time. Sales figures include school purchases and assigned texts, so they overstate sincere affection for the canon.

…Consumer demand is shockingly low overall: American spend 0.2% of their income on all reading materials, barely more than $100 per family per year. Americans used to spend more on reading, but never spent much: Back in 1990, well before the rise of the web, reading absorbed 0.5% of the family budget. Today’s Americans spend about four times as much on tobacco and five times as much on alcohol as they do on reading. Within this small pond, high culture is no big fish. Here are three rankings of the bestselling English-language fiction of all time. Sales figures include school purchases and assigned texts, so they overstate sincere affection for the canon.