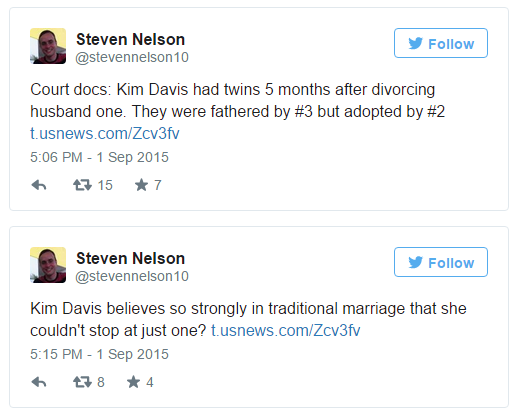

Unless you’re living under a rock, you’ve heard of Kim Davis. She’s the county clerk in Kentucky who is still refusing to give out marriage licenses to same sex couples, despite losing various court battles and having her case rejected by the Supreme Court. She is currently facing contempt charges, but what you really know about Kim Davis from the news media is that she’s been married four times. The hypocrisy is delicious, and reporters cannot get enough of it. Here are a variety of tweets from professional journalists about the story:

Here’s the thing: it’s not unusual to have Christians guilty of hypocrisy. Christians are guilty of lots of things. They are, as a general rule, no better or worse than anybody else from any other faith tradition or none at all. And I don’t think it’s even necessarily out of bounds to comment on it. The glee with which the journalists are relishing in it is a little unseemly, but the fact itself is fair game, in my mind.[ref]And, while I’m at it, I don’t support Kim Davis’s position. I’ve seen someone make the analogy that you can cite religious pacifism as a reason to be exempt from the draft, but you can’t expect to join the military, become an officer, and then refuse to fight based on your religious beliefs. I’m not sure it’s quite as clear-cut in this case–giving out licenses to same-sex marriages wasn’t in the job description when Davis took her job–but all things considered I think the logic is that she isn’t actually marrying anyone, she is merely certifying that these people meet the legal requirements. Which, they do. So she should give out the licenses, even though I am also opposed to same-sex marriage.[/ref]

However, this is the one thing that these journalists aren’t telling you: Davis converted to Christianity about 4 years ago and all of the behavior they are ridiculing her for–all of the divorces and affairs–happened before that point. Since becoming a Christian, Davis has been married to one and only one person. Isn’t that fact also relevant? And yet it tends to get buried in these stories about her, if it is mentioned at all.

These screenshots and the information all from an article at The Federalist, by the way: Kentucky Clerk Didn’t Follow Christianity Before Converting To It.

The article also makes the point that, in general, journalists don’t really have a clue about religion. And they don’t. It’s just another aspect of life in 21st century America. All the folks making the movies, deciding what news to cover (and how), and writing the books we read tend to come from a small class of people who don’t know the first thing about religion and yet–at the same time–have a visceral antipathy towards it and especially towards any forms of religion that bear even a passing resemblance to historical traditions. Perspectives like this one, therefore, are all too rare:

There is plenty of Christian hypocrisy out there, folks. And I don’t have a problem with fouls being called when they occur, even if I know the refs like one team more than the other. All I ask–and I don’t think it’s too much to ask–is to actually wait for a foul to occur before dishing out the penalties.

Last month, I posted a few links on why today’s middle-class salary may actually be

Last month, I posted a few links on why today’s middle-class salary may actually be