There’s been some outrage in the video game community lately about a recent mobile game, Dungeon Keeper, released by EA, a game which, according to said community, embodies the worst and most cynical of what the mobile game industry has to offer. Why the outrage at this particular game? Well…

- It’s an EA game. EA was once the pride of the video game industry. Back in the late ’80s to late ’90s, EA released classics year after year like they couldn’t get rid of them fast enough. In true “you either die a hero…” fashion, however, their phenomenal successes led to interest by the world at large and EA became a corporate behemoth more interested in vacuuming up talent wherever it could find it and putting it to work 80 hours a week pumping out half-finished yearly installments of the most lucrative properties than creating the labors of love that characterized their earlier days. Today, EA, together with Activision, represent to many gamers everything that is unsustainable and wrong with the modern video game industry[ref]This is manifested in EA’s predictable yearly appearances at the top of many “worst company” lists across the web.[/ref].

- It’s a “remake” of a classic title. The original Dungeon Keeper (1997) holds a special place in the hearts of many gamers and was a product of the EA golden age.

- It’s a “broken-by-design” free-to-play (F2P) game[ref]Game developer/designer Jonathan Blow has an interesting discussion of effects of F2P game design here.[/ref]. These types of games are only “free” in the loosest sense of the word. While there is no charge to download and begin playing the game, your progress in the game is punctuated by hours-long wait times to perform even simple actions, forcing players to wait upwards of 24 hours before an action completes and being allowed to queue up another. The only way to actually play the game continuously is to pay real money for resources which eliminate or reduce the timer mechanic. The exchange rate of this resource is such that to have an experience roughly “comparable” (see #4) to the original Dungeon Keeper game, a player would have to pay tens or even hundreds of dollars.

- It is not anything like the original game. Even putting aside the F2P mechanics, very little of the game experience actually resembles the original. If the art assets and the title were changed, it is debatable that anybody would conclude that this new game were even so much as an homage to the first Dungeon Keeper.

Predictably, gamers are upset about the game and its business model. It cheaply cashes in on a classic title while engaging in psychological warfare with players in an attempt to separate them from their money. And what to make of the overwhelmingly positive customer reviews for the game on the App Store? Many are convinced that this means the future generation of players will accept this type of “gameplay” as standard and, as such, it will become increasingly widespread. Gamers are calling EA out, vicious in their criticism of the title and its predatory business model, but is that where the problem is?

I wonder what legitimate justification we have in blaming EA for creating and releasing such a game if people are willing to play it and pay money for it. Obviously, if people weren’t paying for these types of games then there wouldn’t be much reason to continue releasing them. Does EA have any responsibility to adhere to some standard of integrity with regards to the games it releases? In two words: absolutely not. Why should they? The responsibility for the enforcement of “integrity” lays with the customer. That’s the way the it works. It’s a voluntary market.

In my mind, it’s every bit as insidious as EA’s repulsive business practices to imagine companies should cleave to some arbitrary standard of conduct with regard to the type and quality of their products. So long as they are not doing anything illegal, the notion that they’re doing anything objectively wrong or evil is misguided. EA is not your friend, nor should you expect them to be. They’re not on your “side.” They want your money and they’ll happily take it if you’ll give it. The idea of the benevolent business, of companies and individuals laboring for the love and passion of their work with money as simply a byproduct is often symptomatic of a very dangerous and pervasive mindset that seeks to dictate remuneration rather than allow it to emerge a result of free exchange. We can hope for (what we consider) better, yes, but we should not expect it and we should never enforce it.

Companies like EA by and large reflect the tastes of the market they serve, therefore the market shoulders the blame. Dungeon Keeper may be cynical, it may be exploitative, it may even barely qualify as a game at all, but it also represents jobs, and it represents what we, as a game-playing public, have told them we’re prepared to pay for. This is not a defense of the new Dungeon Keeper, of EA or of such so-called “games,” it’s simply an opportunity to take responsibility.

After all, if a seal bathes himself in blood and swims lazily across the nose of a shark, whose fault is it if he gets bitten?

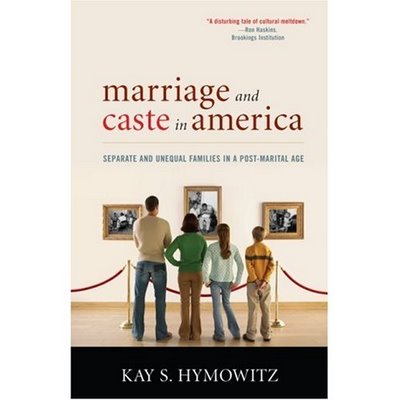

Kay Hymowitz of the Manhattan Institute has an excellent article in The New York Times on single motherhood and the outcomes of children. Hymowitz is no amateur to the subject and she cites an impressive amount of research. For me, one of her most interesting links was a study that “found a connection between the size of a welfare state and rates of both nonmarital births and divorce. Even if you believe that enlarging the infrastructure of support for single-parent families shows compassion for today’s children, it’s not at all obvious that it shows much concern for tomorrow’s.”

Kay Hymowitz of the Manhattan Institute has an excellent article in The New York Times on single motherhood and the outcomes of children. Hymowitz is no amateur to the subject and she cites an impressive amount of research. For me, one of her most interesting links was a study that “found a connection between the size of a welfare state and rates of both nonmarital births and divorce. Even if you believe that enlarging the infrastructure of support for single-parent families shows compassion for today’s children, it’s not at all obvious that it shows much concern for tomorrow’s.”