Recently a friend of mine shared this post in which Jim Wright asks a few “basic questions” about how we would arm teachers. Wright suggests it would be essentially impossible to properly train teachers to respond to school shootings, saying even our soldiers aren’t trained to handle such a situation. He asks who will pay for the training, who the teachers will answer to, which weapons will be allowed, what insurance the school will acquire, and whether a teacher will be held liable for mistakenly shooting an innocent bystander or for failing to stop an active shooter. He claims “the hole is bottomless,” concluding:

I’m asking BASIC questions about this idea of arming up teachers and putting amateurs with guns in schools. Questions that any competent gun operator should ask. You want to put more guns, carried by amateurs, into a building packed full of children. I don’t think I’m being unreasonable here.

Wright is reflecting the skepticism and indignance of many people. In particular some of my friends who are teachers have made posts clearly stating they do not want to carry weapons to school and are dismayed by the thought. More than one of them have shared this video in response.

Several go beyond saying they personally don’t want to carry weapons to asserting no one else should have firearms on school property either, often making demands along the lines “Don’t bring more guns into my school.”

Two quick notes on that last part:

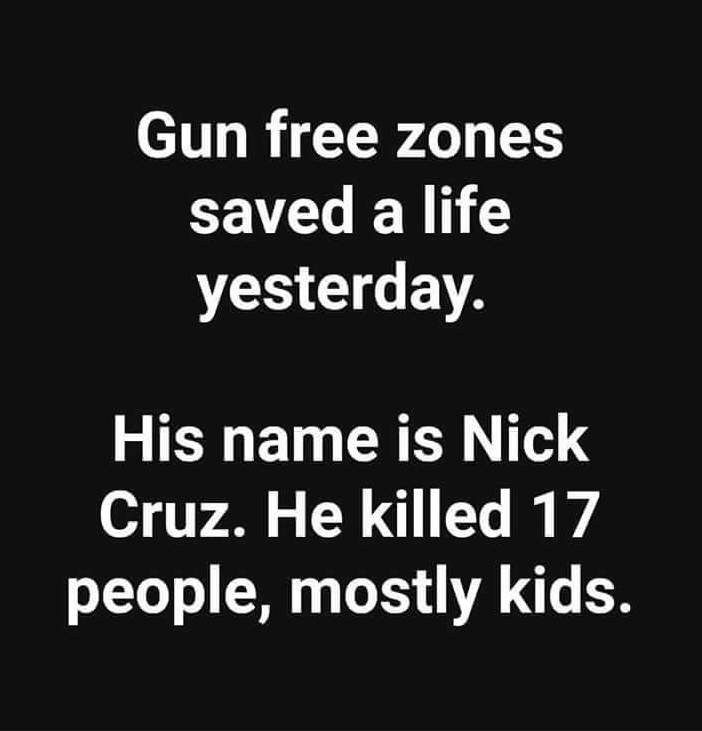

- Assuming any increase in quantity of guns means an increase in danger seems simplistic to me. More guns can increase or decrease danger depending on who is carrying them and why. A gun in the hands of a kid hoping to kill as many people as possible is not equivalent to a gun in the hands of a trained Student Resources Officer or conceal carry permit holder hoping to keep as many people alive as possible.

- In this context, the phrase “my school” is off-putting. Schools don’t belong only to the teachers working in them; they also belong to the children attending and the parents of those children, especially when we are discussing the best ways to protect our children. I understand there are many parents who do not want armed school staff. And there are many parents who do, like me.[ref]According to a recent CBS poll, 44% of those polled favored arming teachers, and 50% opposed the idea. With a margin of error of plus or minus 4 points, it’s a statistical tie. Last year Pew Research Center found similar numbers, notably with no difference in views between parents and non-parents.[/ref] My point here is not that the answer is simple, obvious, or unified; my point is teachers don’t have the only say in this debate.[ref]And I would feel the same way if it was primarily teachers who wanted to bring firearms to school and parents who objected. It’s not about the teachers’ specific stances; it’s about the idea that parents get say over how their children are protected.[/ref]

Anyway, the objections to arming teachers seem to make several assumptions:

-

- We don’t have the resources to arm teachers.

- The logistics of arming teachers are too difficult to disentangle.

- Teachers don’t want to be armed.[ref]Update, 2/26/18: A 2013 poll of 11,000 educators found that 36.3% of educators own a firearm, and 37.1% of that group would be likely to bring the firearm to school if allowed. In other words, a little over 1 in 8 educators both own firearms and would like to be able to carry at school.[/ref]

- Armed teachers would make schools less safe, not more safe.

In terms of the law, as of May 2016, there were 17 states that banned conceal carry guns on college campuses; 1 state (Tennessee) banned students and the public from carryng guns on campus but allowed faculty members to do so; 8 states allowed conceal carry guns; and the remaining 24 states left the decision to the school. Of course this information is for only college campuses, not K-12 schools.[ref]I’ve yet to find a source summarizing state-by-state policy on K-12 schools. If you know of one, please share.[/ref]

Given the option, many school districts already allow their teachers to be armed. This fact alone puts the first three assumptions to rest. Apparently resources, logistics, and desire were not dealbreakers in arranging to have armed school employees on campus. Here is an excerpt from a 2016 Washington Post article:

The Kingsburg Joint Union High School District in Kingsburg, Ca., is the latest district to pass such a measure. At a school board meeting on Monday, the Fresno Bee reported, members unanimously approved a policy that allows district employees to carry a concealed firearm within school bounds.

The employees will be selected by the superintendent, and will have to complete a training and evaluation process. The new policy was made effective immediately.

While proposals to arm teachers have been familiar refrains in Texas and Indiana, the passing of such a mandate on the West Coast signals that the strategy is being considered elsewhere in the country.

In fact, the Folsom Cordova Unified School District covering the cities of Folsom, Rancho Cordova and Mather, Calif., has allowed employees to bring guns to school since 2010, but only revealed the policy to parents last month.

Some people against the idea of arming teachers say it will create an intimidating environment for kids, but note Folsom Cordova’s school district allowed it for 5-6 years before anyone even knew about it. Arming teachers had so little impact on the daily school environment people couldn’t even tell it had happened.

In the wake of the most recent shooting, more school boards are following suit, voting unanimously to allow trained employees to carry concealed weapons.

People opposed to arming teachers seem to envision a bureaucratic and expensive process that results in an intimidating environment where teachers nervously walk the hallways with rifles over their shoulders. The reality is that arming teachers has so far consisted of allowing those who want to be armed to first get training and then either carry concealed weapons or keep weapons locked in safes. From what I can tell, the individuals who want to be armed cover the costs of the training, permit, and firearm themselves. Again, the school’s resources, logistics, and the teacher’s desire don’t seem to be issues.

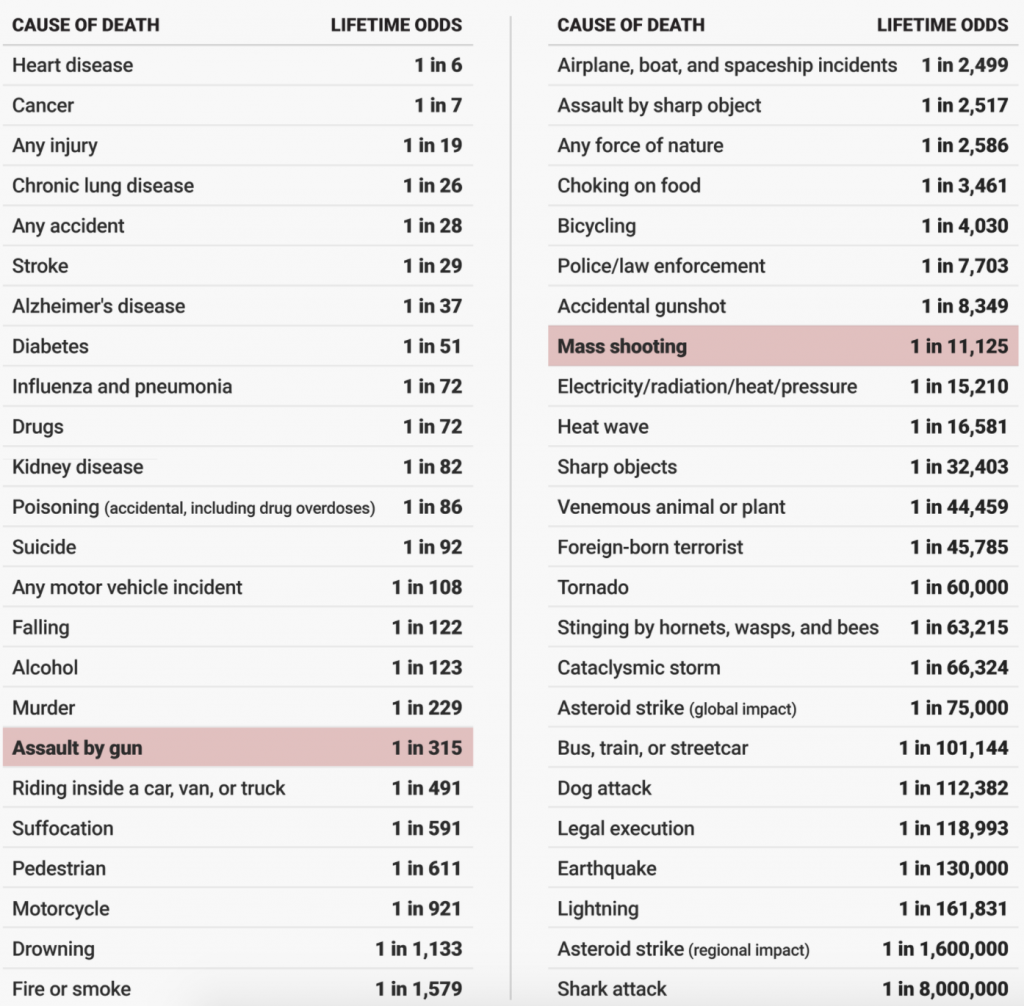

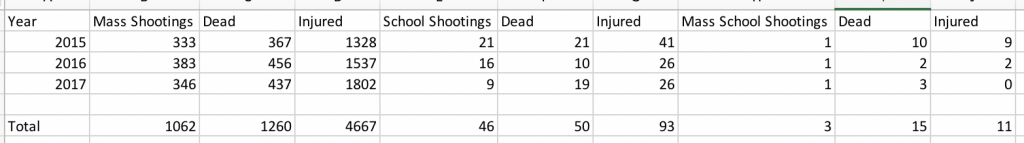

To my mind, the only real issue is the question of whether allowing teachers to carry concealed weapons will overall increase or decrease student and staff safety. Despite how horrifying school shootings are, they are also exceedingly rare. And while I have no specific data on this, I suspect that even if firearms were permitted on all schools across the country, relatively few teachers and other school staff would choose to carry them. The odds seem very low of a school shooting happening in such a way that an armed staff member would even be present to react. Meanwhile, having legal guns on campus opens the door to accidental injuries. Some of my friends against armed school staff have posted stories about teachers forgetting their firearm or having it stolen while on school property.[ref]It looks like both incidents involved teachers bringing firearms to school without permission, and it’s unclear what training either teacher had. Still, it’s also possible for a trained concealed carry holder to make a mistake.[/ref] There’s a cost-benefit question here: if arming teachers increases the chances of accidentally injuring or even killing students but also increases the chances of saving lives during school shootings, how do we quantify those two factors and weigh them against each other?

I know of no hard data here. We do know that in our country, in general, guns are used more often in accidental deaths than in justifiable homicide. However we aren’t just considering accidental deaths but also accidental injuries, and we aren’t just considering justifiable homicide but also self-defense that involves injuring but not killing the shooter or even not firing the gun at all but brandishing it and getting the shooter to stand down. Additionally the overall statistics for the whole country include people who have received no training in the safe use and storage of firearms, whereas conceal and carry permits typically require training, and individual school districts could require further training as needed. Apparently there are quite a few school districts that have allowed armed staff for years, and I have not been able to find any stories of accidental deaths or even injuries from a teacher’s gun on school property.

Meanwhile, it is intuitive to me that if a teacher were to find herself in the position where there is a mass shooter attacking her or her students, both she and her students would have a greater chance of survival if she had a gun than if she did not. When Sandy Hook happened, I cried as I read in absolute horror about Lauren Rousseau and her first graders, completely trapped and defenseless. Even at the time I wondered if it would have been different if she had had a gun.[ref]This is not to suggest Rousseau would have wanted to carry a gun to school even if she could have. I have no idea. I would expect typically the type of people interested in teaching children are probably not the type of people most likely interested in carrying firearms. My argument here is definitely not that anyone who is uncomfortable with firearms should have to carry one. My argument is that if a teacher or other staff specifically want to be able to carry a concealed firearm at school, they should be able to. They should have the right to defend themselves and their students.[/ref]

A note here: I don’t want the world we live in, the society we live in, to require first grade teachers to need guns. I don’t want there to be any guns on any school property at all. I don’t want children to have to do active shooter drills, or teachers to have to be trained to recognize gun shots, or parents to drop their kids off and worry if they will be safe each day. It’s awful. It’s infuriating and heartbreaking, and sometimes I can hardly stand to think about it.

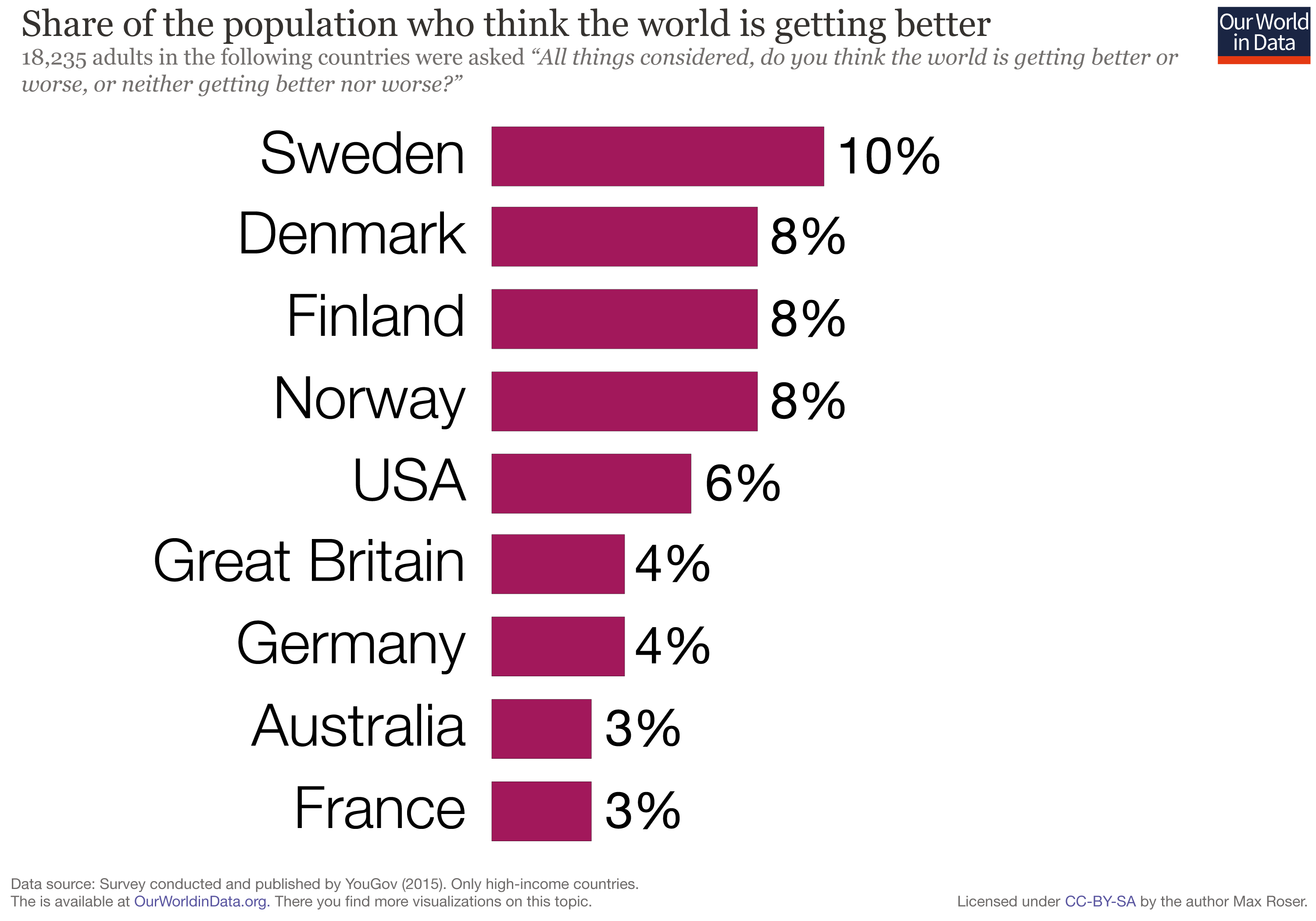

But I also don’t think we have a way to 100% ensure that deranged or evil people will not be able to show up and try to kill as many unarmed teachers and children as possible. In fact, given our country’s unique relationship with guns, and our relatively unique 2nd amendment, I think preventing such shootings is ridiculously difficult. I still think we should try, but I don’t think our efforts to stem the death toll should be limited only to preventing shooters from showing up in the first place. I think we should also have efforts to address what innocent people can do if a shooter does show up.

As I write this post, a news story is breaking suggesting that not only did the School Resources Officer fail to engage Nicholas Cruz, but so did three additional deputies present during the shooting. All four officers remained outside the school while Cruz shot unarmed teachers and students. Some opponents to arming teachers point out that if even trained officers struggle to engage a mass shooter, how can we expect teachers to be able to handle it? But this question presumes that teachers get any choice; the reality is that if the shooter is already in the school and breaking into the classroom, the teacher will have to face the shooter anyway. And I can’t help but wonder: if police won’t engage the shooter, how can we disarm teachers and tell them to wait for the police?

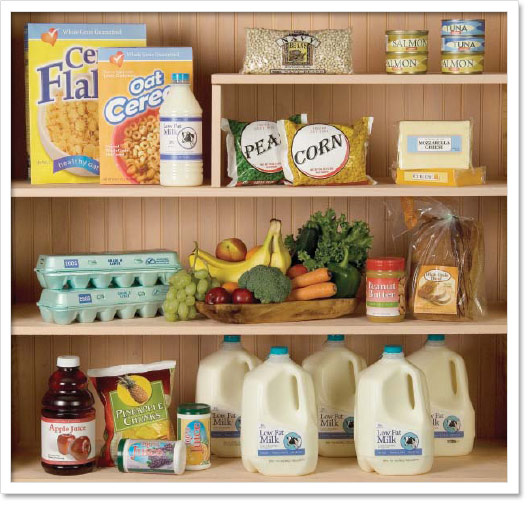

Some of the foods you can purchase through WIC.

Some of the foods you can purchase through WIC. The controversial Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson has a new book out titled

The controversial Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson has a new book out titled