Pew Research Center has a new study out on American’s religious beliefs. Their previous research on the rise of the “nones” (i.e., the unchurched or religiously unaffiliated) received a lot of press with many claiming that religious belief was on the decline. Sociologist Rodney Stark has been calling out the misleading nature of these numbers, pointing out that a lack of religious affiliation does not say much about the person’s beliefs. His criticisms are based on his detailed, large-scale survey of Americans’ beliefs and practices as well as his analysis of cross-country data. And now, Pew’s recent research seems to indicate that Stark had a point:

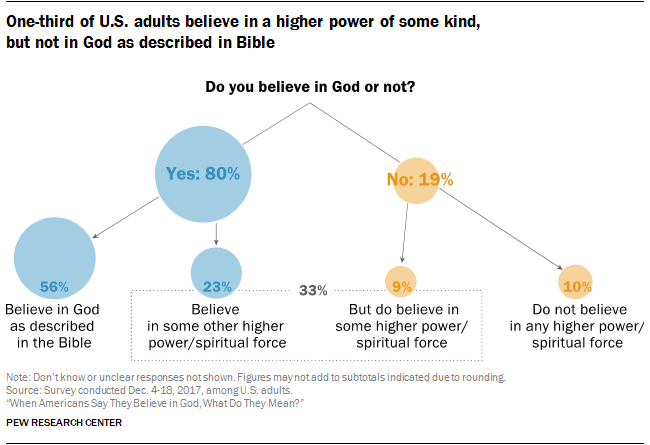

A new Pew Research Center survey of more than 4,700 U.S. adults finds that one-third of Americans say they do not believe in the God of the Bible, but that they do believe there is some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe. A slim majority of Americans (56%) say they believe in God “as described in the Bible.” And one-in-ten do not believe in any higher power or spiritual force.

…The survey questions that mention the Bible do not specify any particular verses or translations, leaving that up to each respondent’s understanding. But it is clear from questions elsewhere in the survey that Americans who say they believe in God “as described in the Bible” generally envision an all-powerful, all-knowing, loving deity who determines most or all of what happens in their lives. By contrast, people who say they believe in a “higher power or spiritual force” – but not in God as described in the Bible – are much less likely to believe in a deity who is omnipotent, omniscient, benevolent and active in human affairs.

And what of the so-called “nones”?:

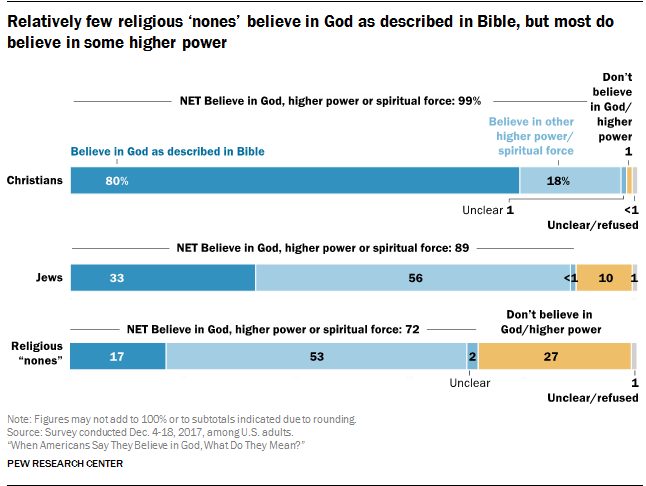

Compared with Christians, Jews and people with no religious affiliation are much more likely to say they do not believe in God or a higher power of any kind. Still, big majorities in both groups do believe in a deity (89% among Jews, 72% among religious “nones”), including 56% of Jews and 53% of the religiously unaffiliated who say they do not believe in the God of the Bible but do believe in some other higher power of spiritual force in the universe. (The survey did not include enough interviews with Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus or respondents from other minority religious groups in the United States to permit separate analysis of their beliefs.)

As Stark writes,

The world is more religious than it has ever been. Around the globe, four out of every five people claim to belong to an organized faith, and many of the rest say they attend worship services. In Latin American, Pentecostal Protestant churches have converted tens of millions, and Catholics are going to Mass in unprecedented numbers. There are more churchgoing Christians in Sub-Saharan African than anywhere else on earth, and China may soon become home of the most Christians. Meanwhile, although not growing as rapidly as Christianity, Islam enjoys far higher levels of member commitment than it has for many centuries, and the same is true for Hinduism. In fact, of all the great world religions, only Buddhism may not be growing…[D]espite [the] confident proclamations about the decline of religion, Pew’s findings were certainly misleading and probably wrong. Consider only one fact: the overwhelming majority of Americans who say they have no religious affiliation pray and believe in angels! How irreligious is that?[ref]The Triumph of Faith, pg. 1-2.[/ref]

Furthermore,

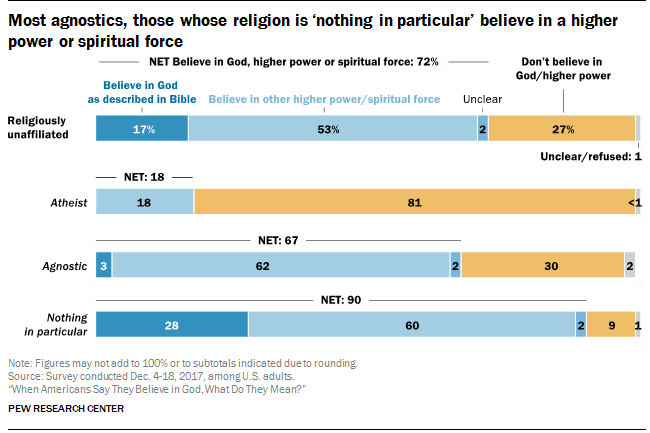

The [Pew] findings would seem to be clear: the number of Americans who say their religious affiliation is “none” has increased from about 8 percent in 1990 to about 22 percent in 2014. But what this means is not so obvious, for, during this same period, church attendance did not decline and the number of atheists did not increase. Indeed, the percentage of atheists in America has stayed stead at about 4 percent since a question about belief in God was first asked in 1944. In addition, except for atheists, most of the other “nones” are religious in the sense that they pray (some pray very often) and believe in angels, in heaven, and even in ghosts. Some are also rather deeply involved in “New Age” mysticisms.

So who are these “nones,” and why is their number increasing–if it is? Back in 1990 most Americans who seldom or never attended church still claimed a religious affiliation when asked to do so. Today, when asked their religious preference, instead of saying Methodist or Catholic, now a larger proportion of nonattenders say “none,” by which most seem to mean “no actual membership.” The entire change has take place within the nonattending group, and the nonattending group has not grown.

In other words, this change marks a decrease only in nominal affiliation, not an increase in irreligion. So whatever else it may reflect, the change does not support claims for increased secularization, let alone a decrease in the number of Christians. It may not even reflect an increase in those who say they are “nones.” The reason has to do with response rates and the accuracy of surveys.[ref]Ibid., 190.[/ref]

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects.

Immigration policy is controversial topic in 2018. In response to refugee crises and legal situations that can break up families, the LDS Church announced its “I Was a Stranger” relief effort and released a statement encouraging solutions that strengthens families, keeps them together, and extends compassion to those seeking a better life. This article seeks to shed light on a correct understanding of immigration and its effects. Walker Wright gives a brief scriptural overview of migration, explores the public’s attitudes toward immigration, and reviews the empirical economic literature, which shows that (1) fears about immigration are often overblown or fueled by misinformation and (2) liberalizing immigration restrictions would have positive economic effects.

Stephen Prothero, Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know–And Doesn’t (HarperCollins, 2007): “The United States is one of the most religious places on earth, but it is also a nation of shocking religious illiteracy.

Stephen Prothero, Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know–And Doesn’t (HarperCollins, 2007): “The United States is one of the most religious places on earth, but it is also a nation of shocking religious illiteracy. Steven Reiss, The 16 Strivings for God: The New Psychology of Religious Experience (Mercer University Press, 2015): “This ground-breaking work will change the way we understand religion. Period. Previous scholars such as Freud, James, Durkheim, and Maslow did not successfully identify the essence of religion as fear of death, mysticism, sacredness, communal bonding, magic, or peak experiences because religion has no single essence. Religion is about the values motivated by the sixteen basic desires of human nature. It has mass appeal because it accommodates the values of people with opposite personality traits. This is the first comprehensive theory of the psychology of religion that can be scientifically verified. Reiss proposes a peer-reviewed, original theory of mysticism, asceticism, spiritual personality, and hundreds of religious beliefs and practices. Written for serious readers and anyone interested in psychology and religion (especially their own), this eminently readable book will revolutionize the psychology of religious experience by exploring the motivations and characteristics of the individual in their religious life” (

Steven Reiss, The 16 Strivings for God: The New Psychology of Religious Experience (Mercer University Press, 2015): “This ground-breaking work will change the way we understand religion. Period. Previous scholars such as Freud, James, Durkheim, and Maslow did not successfully identify the essence of religion as fear of death, mysticism, sacredness, communal bonding, magic, or peak experiences because religion has no single essence. Religion is about the values motivated by the sixteen basic desires of human nature. It has mass appeal because it accommodates the values of people with opposite personality traits. This is the first comprehensive theory of the psychology of religion that can be scientifically verified. Reiss proposes a peer-reviewed, original theory of mysticism, asceticism, spiritual personality, and hundreds of religious beliefs and practices. Written for serious readers and anyone interested in psychology and religion (especially their own), this eminently readable book will revolutionize the psychology of religious experience by exploring the motivations and characteristics of the individual in their religious life” ( Alfred R. Mele, Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will (Oxford University Press, 2014): “Does free will exist? The question has fueled heated debates spanning from philosophy to psychology and religion. The answer has major implications, and the stakes are high. To put it in the simple terms that have come to dominate these debates, if we are free to make our own decisions, we are accountable for what we do, and if we aren’t free, we’re off the hook. There are neuroscientists who claim that our decisions are made unconsciously and are therefore outside of our control and social psychologists who argue that myriad imperceptible factors influence even our minor decisions to the extent that there is no room for free will. According to philosopher Alfred R. Mele, what they point to as hard and fast evidence that free will cannot exist actually leaves much room for doubt. If we look more closely at the major experiments that free will deniers cite, we can see large gaps where the light of possibility shines through. In Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will, Mele lays out his opponents’ experiments simply and clearly, and proceeds to debunk their supposed findings, one by one, explaining how the experiments don’t provide the solid evidence for which they have been touted. There is powerful evidence that conscious decisions play an important role in our lives, and knowledge about situational influences can allow people to respond to those influences rationally rather than with blind obedience. Mele also explores the meaning and ramifications of free will. What, exactly, does it mean to have free will — is it a state of our soul, or an undefinable openness to alternative decisions? Is it something natural and practical that is closely tied to moral responsibility? Since evidence suggests that denying the existence of free will actually encourages bad behavior, we have a duty to give it a fair chance” (

Alfred R. Mele, Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will (Oxford University Press, 2014): “Does free will exist? The question has fueled heated debates spanning from philosophy to psychology and religion. The answer has major implications, and the stakes are high. To put it in the simple terms that have come to dominate these debates, if we are free to make our own decisions, we are accountable for what we do, and if we aren’t free, we’re off the hook. There are neuroscientists who claim that our decisions are made unconsciously and are therefore outside of our control and social psychologists who argue that myriad imperceptible factors influence even our minor decisions to the extent that there is no room for free will. According to philosopher Alfred R. Mele, what they point to as hard and fast evidence that free will cannot exist actually leaves much room for doubt. If we look more closely at the major experiments that free will deniers cite, we can see large gaps where the light of possibility shines through. In Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will, Mele lays out his opponents’ experiments simply and clearly, and proceeds to debunk their supposed findings, one by one, explaining how the experiments don’t provide the solid evidence for which they have been touted. There is powerful evidence that conscious decisions play an important role in our lives, and knowledge about situational influences can allow people to respond to those influences rationally rather than with blind obedience. Mele also explores the meaning and ramifications of free will. What, exactly, does it mean to have free will — is it a state of our soul, or an undefinable openness to alternative decisions? Is it something natural and practical that is closely tied to moral responsibility? Since evidence suggests that denying the existence of free will actually encourages bad behavior, we have a duty to give it a fair chance” ( Brink Lindsey, Human Capitalism: How Economic Growth Has Made Us Smarter–and More Unequal (Princeton University Press, 2013): “What explains the growing class divide between the well educated and everybody else? Noted author Brink Lindsey, a senior scholar at the Kauffman Foundation, argues that it’s because economic expansion is creating an increasingly complex world in which only a minority with the right knowledge and skills–the right “human capital”–reap the majority of the economic rewards. The complexity of today’s economy is not only making these lucky elites richer–it is also making them smarter. As the economy makes ever-greater demands on their minds, the successful are making ever-greater investments in education and other ways of increasing their human capital, expanding their cognitive skills and leading them to still higher levels of success. But unfortunately, even as the rich are securely riding this virtuous cycle, the poor are trapped in a vicious one, as a lack of human capital leads to family breakdown, unemployment, dysfunction, and further erosion of knowledge and skills. In this brief, clear, and forthright eBook original, Lindsey shows how economic growth is creating unprecedented levels of human capital–and suggests how the huge benefits of this development can be spread beyond those who are already enjoying its rewards” (

Brink Lindsey, Human Capitalism: How Economic Growth Has Made Us Smarter–and More Unequal (Princeton University Press, 2013): “What explains the growing class divide between the well educated and everybody else? Noted author Brink Lindsey, a senior scholar at the Kauffman Foundation, argues that it’s because economic expansion is creating an increasingly complex world in which only a minority with the right knowledge and skills–the right “human capital”–reap the majority of the economic rewards. The complexity of today’s economy is not only making these lucky elites richer–it is also making them smarter. As the economy makes ever-greater demands on their minds, the successful are making ever-greater investments in education and other ways of increasing their human capital, expanding their cognitive skills and leading them to still higher levels of success. But unfortunately, even as the rich are securely riding this virtuous cycle, the poor are trapped in a vicious one, as a lack of human capital leads to family breakdown, unemployment, dysfunction, and further erosion of knowledge and skills. In this brief, clear, and forthright eBook original, Lindsey shows how economic growth is creating unprecedented levels of human capital–and suggests how the huge benefits of this development can be spread beyond those who are already enjoying its rewards” ( Gretchen Rubin, Better Than Before: What I Learned About Making and Breaking Habits–to Sleep More, Quit Sugar, Procrastinate Less, and Generally Build a Happier Life (Broadway Books, 2015): “How do we change? Gretchen Rubin’s answer: through habits. Habits are the invisible architecture of everyday life. It takes work to make a habit, but once that habit is set, we can harness the energy of habits to build happier, stronger, more productive lives. So if habits are a key to change, then what we really need to know is: How do we change our habits? Better than Before answers that question. It presents a practical, concrete framework to allow readers to understand their habits—and to change them for good. Infused with Rubin’s compelling voice, rigorous research, and easy humor, and packed with vivid stories of lives transformed, Better than Before explains the (sometimes counter-intuitive) core principles of habit formation. Along the way, Rubin uses herself as guinea pig, tests her theories on family and friends, and answers readers’ most pressing questions—oddly, questions that other writers and researchers tend to ignore:

Gretchen Rubin, Better Than Before: What I Learned About Making and Breaking Habits–to Sleep More, Quit Sugar, Procrastinate Less, and Generally Build a Happier Life (Broadway Books, 2015): “How do we change? Gretchen Rubin’s answer: through habits. Habits are the invisible architecture of everyday life. It takes work to make a habit, but once that habit is set, we can harness the energy of habits to build happier, stronger, more productive lives. So if habits are a key to change, then what we really need to know is: How do we change our habits? Better than Before answers that question. It presents a practical, concrete framework to allow readers to understand their habits—and to change them for good. Infused with Rubin’s compelling voice, rigorous research, and easy humor, and packed with vivid stories of lives transformed, Better than Before explains the (sometimes counter-intuitive) core principles of habit formation. Along the way, Rubin uses herself as guinea pig, tests her theories on family and friends, and answers readers’ most pressing questions—oddly, questions that other writers and researchers tend to ignore: Drew Magary, The Hike: A Novel (Penguin, 2016): “When Ben, a suburban family man, takes a business trip to rural Pennsylvania, he decides to spend the afternoon before his dinner meeting on a short hike. Once he sets out into the woods behind his hotel, he quickly comes to realize that the path he has chosen cannot be given up easily. With no choice but to move forward, Ben finds himself falling deeper and deeper into a world of man-eating giants, bizarre demons, and colossal insects. On a quest of epic, life-or-death proportions, Ben finds help comes in some of the most unexpected forms, including a profane crustacean and a variety of magical objects, tools, and potions. Desperate to return to his family, Ben is determined to track down the “Producer,” the creator of the world in which he is being held hostage and the only one who can free him from the path. At once bitingly funny and emotionally absorbing, Magary’s novel is a remarkably unique addition to the contemporary fantasy genre, one that draws as easily from the world of classic folk tales as it does from video games. In The Hike, Magary takes readers on a daring odyssey away from our day-to-day grind and transports them into an enthralling world propelled by heart, imagination, and survival” (

Drew Magary, The Hike: A Novel (Penguin, 2016): “When Ben, a suburban family man, takes a business trip to rural Pennsylvania, he decides to spend the afternoon before his dinner meeting on a short hike. Once he sets out into the woods behind his hotel, he quickly comes to realize that the path he has chosen cannot be given up easily. With no choice but to move forward, Ben finds himself falling deeper and deeper into a world of man-eating giants, bizarre demons, and colossal insects. On a quest of epic, life-or-death proportions, Ben finds help comes in some of the most unexpected forms, including a profane crustacean and a variety of magical objects, tools, and potions. Desperate to return to his family, Ben is determined to track down the “Producer,” the creator of the world in which he is being held hostage and the only one who can free him from the path. At once bitingly funny and emotionally absorbing, Magary’s novel is a remarkably unique addition to the contemporary fantasy genre, one that draws as easily from the world of classic folk tales as it does from video games. In The Hike, Magary takes readers on a daring odyssey away from our day-to-day grind and transports them into an enthralling world propelled by heart, imagination, and survival” (