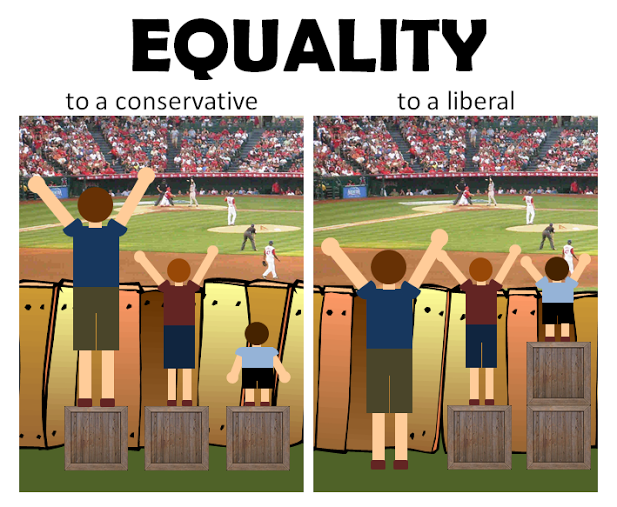

Conservatives have a reputation for being mean: callous, unthinking, insensitive, cruel. You get the picture.[ref]Liberals, perhaps, have a corresponding reputation for being dumb: naive, sentimental, idealistic. But let’s just stick with conservatives for today.[/ref] Part of the reason conservatives have that reputation is because it’s politically advantageous for liberals to portray them that way. But part of it comes from conservatives themselves who–to a degree that I think is more true than with liberal commentators–tend to say things that are combative, adversarial, and aggressive. The question I’ll address today is this: why?

I’d like to ask of you, the reader, to entertain the notion that it might be something other than sheer meanness that animates the way some conservatives appear to pick fights unnecessarily. And this might be tough, because I’m going to focus on Ann Coulter, who is arguably the meanest of all conservative commentators out there commentating today. I have plenty of friends who will go into paroxysms of rage at the mere mention of her name or sight of her picture, but I’ve never been one to shy away from controversial topics. Besides, I’m not going to try to convince anyone to accept her points of view or nominate her for “Most Compassionate.,” I am, however, going to speculate on what it is that makes her write the way she does, and further speculate that it is something other than a heart as tarnished and black as coal.

I discovered Ann Coulter as an undergrad and for me her books[ref]Treason and How to Talk to a Liberal (If You Must) are the two that I read at the time.[/ref] were a revelation. It turns out, however, that they were also not entirely accurate. The first example that comes to mind is from her book Slander where–in the first edition–she alleged that the NYT ignored Dale Earnhardt’s death as evidence of the disconnect between red and blue America. Except, of course, that the NYT did cover it:

The New York Times did, in fact, cover Earnhardt’s death the same day that he died: sportswriter Robert Lipsyte authored an article for the front page that was published on February 18, 2001. Another front page article appeared in the Times on the following day.

It was also from Coulter that I learned that all the racist white Southerners during Jim Crow were Democrats, but she left out the part where they all switched to Republican after the Democratic Party embraced civil rights.[ref]And there died the last remnants of my capacity to care about political parties in America other than tactically.[/ref] But the real end of my Ann Coulter fandom came when I went to see her speak and stayed afterwards to get my books signed. In fairness to her, I was the last person in line and she was probably really, really tired. But when I asked her about coalition-building with moderate, patriotic Muslim-Americans her response (which I cannot recall with accuracy and won’t try to reproduce) was so utterly dismissive that it left me completely disenchanted.

I know that for a lot of people admitting that you liked Ann Coulter at any time in the past is something you would confide only in embarrassed tones and with lots of assurances that you were young and stupid then. But I’m not embarrassed about it. I’m always trying to find aspects of common wisdom that everyone else accepts that are actually wrong. That’s a dangerous quest ’cause when the common wisdom is right you look doubly like a fool, but I’m not ashamed of being willing to look like a fool for the sake of bucking conventional wisdom. And this seems like a good time for some William James:

He who says ‘Better to go without belief forever than believe a lie!’ merely shows his own preponderant private horror of becoming a dupe…. This fear he slavishly obeys. …For my own part, I have also a horror of being duped; but I can believe that worse things than being duped may happen to a man in this world. . . .It is like a general informing his soldiers that it is better to keep out of battle forever than to risk a single wound. Not so are victories either over enemies or over nature gained. Our errors are surely not such awfully solemn things. In a world where we are so certain to incur them in spite of all our caution, a certain lightness of heart seems healthier than this excessive nervousness on their behalf.

Now, returning to Ann Coulter, even though I can’t consider myself a fan in an unqualified sense any more, I still do carry both respect and affection for her and her writing. I think she’s often but not always very funny and always smart even when she’s wrong. But I’ve learned a couple of other things that, naive as it might be, make me think I have some insight into her character and–along with it–the fundamental reason why conservatives come across as mean, callous, etc.

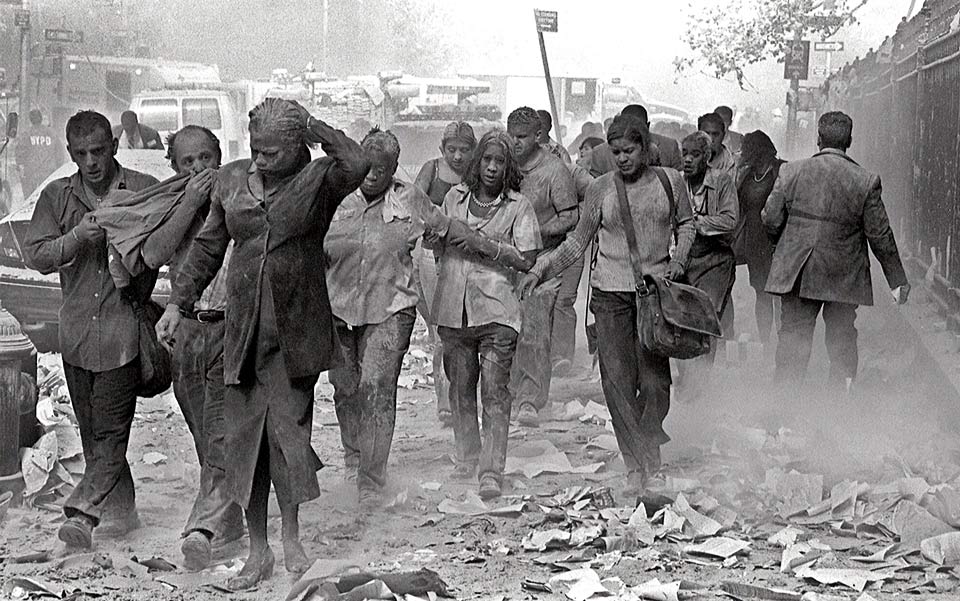

One of the big insights for me came when a couple of students threw pies at Ann Coulter during a speech in 2004. Pie-throwing, or just pieing, is one of those things that sounds funny until you think about it seriously, as this writer for the New Republic did:

As a concept, throwing pies at pompous bores is pleasing. As a reality, it’s not pleasing at all. It’s one thing to parody, to tease, to lampoon. Jon Stewart throws metaphorical pies at hypocrites and fools several days a week. It’s another thing to see a face distorted and dripping with foam or custard as the person sits blinking and trying to take stock of what happened. Just watch Anita Bryant weeping.[ref]Check out the article for videos of people being pied, including Ann Coulter.[/ref]

In addition to the initial incident, however, Coulter later claimed that the local DA dropped the charges against the students against her wishes. Media Matter blamed Coulter because she didn’t show up at the trial. Coulter, for her part, wondered what strange legal system Arizona must have such that if a victim doesn’t show up at a trial the charges are automatically dropped, and further claims that when she asked if she was required to attend and when and where the trial would be held, she got no response at all. I don’t think it’s obvious from those two posts what the truth is, but I do think that in most cases calling someone a liar because they didn’t show up at the trial of someone who physically assaulted them would be justifiably called “victim-blaming.” I’d call the whole thing–from pie-throwing to mocking–simply this: bullying.

Sure, sure: she brings it upon herself. You can say that about a lot of people who are bullied. That’s because being bullied tends to make people scared and angry. We understand that when it’s about a normal human being, but for some reason we in America don’t treat famous people like normal human beings. Although they are.[ref]This is something I think about a lot, by the way, and not just with conservative pundits. The way Big Entertainment chews up and spits out starlets and child actors like Lindsay Lohan or Britney Spears is, I think, a truly grim indictment of our culture. Everyone hates the paparazzi, but the mags that run the pictures don’t seem to be facing any boycotts.[/ref]

Look, as long as I’m writing a somewhat personal blog entry, I’ll go all in. First, I was bullied a lot myself in middle school. It was what I’d call pretty severe, including things like people vandalizing clothes in my locker while I was in PE, teachers leading the kids in making fun of me, and administrators calling me a liar when my parents tried to stand up for me. Second, I have parents who are–at least in Mormon circles–moderately famous. And people treat them really poorly sometimes. I’ve seen my mother publicly lambasted and called a narcissist stooge of the patriarchy who is in it for the money by prominent individuals who should know better. It’s not just that the accusations are flagrantly false[ref]They are, and even though I’m biased let me just tell you: they really are.[/ref], it’s that they are the kind of accusations that you just wouldn’t make about a fellow human being. You make them against symbols, dehumanized enemies, or inhuman icons. Not against your brother, your sister, or your neighbor.

So how does it feel to be Ann Coulter? To have people throw pies at you and have other people treat it like a joke? To have people organize to shout you down when you are invited to speak, and to have their actions lionized and applauded as though a mob of angry people shouting at an unarmed woman in high heels is the paragon of bravery.[ref]Truth to power, indeed.[/ref]

I get it. The immediate response is: “I’m not Ann.” As in, I don’t voluntarily write a bunch of hateful stuff. So, just to recap, this woman invites criticism by having loud, offensive opinions that aren’t popular. If she didn’t want to be physically assaulted, she should just keep her mouth shut. You could even say she’s asking for it, couldn’t you?

Or maybe she deserves what’s coming ’cause she got paid. Well, I think Kirsten Dunst and Jennifer Lawrence and the other women who had their iCloud accounts hacked and personal photos stolen probably get paid a lot for their work–some of which involves looking beautiful–but call me crazy if that just doesn’t justify stealing photos, posting them online, or looking at them either. Being well-compensated for work shouldn’t be an excuse to dehumanize someone.

OK, well maybe Ann Coulter deserves it because she says mean things for money. I’m skeptical of that. First of all: nobody does anything for just one reason. I really doubt that Coulter or anyone else (say, Michael Moore) has such a pure profit-motive. Does anyone think that Ann was just going through life and then was like, “Hey, I know a great way to get rich. I’ll say really horrible things for money!” I’m sure that Coulter has some sincere principles. I’m sure Michael Moore does, too. I’m sure at least part of what she does is because she thinks it’s the right thing to do. After all, doesn’t everyone think–usually sincerely–that they are a good guy?[ref]If you imagine any other human being to be consciously operating on some nefarious motive, like pure greed, you’re probably already seriously off-track. Real life people are neither angels nor demons.[/ref] I’m sure her good intentions are also warped by the riches and adulation of the fans that love her. She wouldn’t be human if they were not. But my question, again, is does this justify how she is treated? I don’t think it does. The thing with all these rationalizations and excuses is just that: they are rationalizations and excuses. We know better.

Last personal note: Earlier this week I posted a long article about the myth that rape is exclusively about power. The immediate response from one of my more vocal critics was to call me a misogynist on his FB wall, and then there was a pile-on after that. As a general rule, I think of myself as someone who has relatively thick skin. I’ve debated on the Internet for many, many years and have been called all kinds of things. Usually, I laugh. I have also called people all kinds of things, although I regret that and have tried to reform.[ref]I know of at least two people I’ve made cry in debates. One in-person, one online. I’m not proud of that, but it shows you the kind of tactics I used to use.[/ref]

But there’s something different about being accused in abstentia. When someone is screaming at me and calling me names it might not be pleasant, but in a perverse way I know I’m important enough to warrant an excess of emotion on their part. It might be totally dysfunctional, but we’re communicating. We are in a social relationship. I am still connected. When a group of people mock you and you’re not even there, it feels different. It feels worse. It feels like being made into a non-person. As we learned from Kreacher in Harry Potter, the cruelest opposite of love is not hate. “Indifference and neglect often do more damage than outright dislike,” as J. K. Rowling put it. The reason that indifference and neglect are worse than hatred is that they amount to treating a human being like a thing instead of like a person. It is the absolute negation of our essential worth.

Just to twist the knife a bit, of course, the reason I wrote that piece is because I have known many women in my life who have suffered from sexual violence and I want to do something about it. For me, “doing something about it,” has to start with really understanding the problem. I may have been flagrantly wrong in my approach (although my critics haven’t swayed me that far yet), but whether I was right or wrong wasn’t even relevant to the attacks. The issue wasn’t how good my arguments were. The issue was what a terrible human being I am.[ref]Incidentally, someone should really warn my wife that she’s married to a misogynist.[/ref]

I think I have a pretty good handle on my own insignificance. I see the web traffic to my blog, and I know what web traffic is to some really major blogs. I am not a public figure. I don’t meet Wikipedia’s notability criteria. There are not hundreds or thousands or even millions of people out there talking about me. There’s this one rather odd individual who seems to have an unhealthy fixation and–by extension–some of his friends. I can shrug, not read his page in the future, and get on with my life. But this is true precisely to the extent that I’m inconsequential. Someone like Ann Coulter doesn’t really have that option and so when I think about how she goes about her day-to-day life, I have empathy for her and the vitriol she sometimes spews. I can see that feeling like you are living under siege would make lots of people want to lash out.

That doesn’t mean I think lashing out is OK. Understanding is not excusing. To go back to my own past again, when I was in middle school and the bullying was at its worst I didn’t really have friends.[ref]The birthday party where only one kid showed up comes to mind. But, hey: it could have been nobody.[/ref] But I did have a group of kids who hung out at school before first class purely because we were all in the same place (the library) hiding from our own bullies. We put up with a lot of weird anti-social and unpleasant behavior from each other. Partially because we had to but also, I think, because we understood each other. We knew we weren’t exactly the best versions of ourselves. We knew that all of us would be smarter, more gracious, more competent, and better if our circumstances were a little different than they were.

This post is going to be a big joke to a lot of people who believe that trying to find empathy for rich folks, or for hate-mongers is a waste of time and who find the entire idea of a vulnerable pundit to be laughable. Believe me, lots of people will take from this, “Nathaniel likes Ann Coulter, ergo he is even stupider and more hateful than I thought!” and nothing more. I’m sad about that, but unwilling to modify the post for the sake of my reputation, such as it is. The message is what it is, and the command is to “love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you.” (Matthew 5:44) By golly I just don’t see an exception for income or fame or ideology any more than I do for race or gender or sexuality.

The decision I’ve made is to remain unaffected by the mockery and scorn that comes my way (to the extent that I can) and try to stay true to my Christian ideals. Frankly, there’s very little of it (see above, re: my own insignificance) and if I can’t handle this trickle then that’s just sad. I will try to love my neighbor: even the rich ones. Even the famous ones. Even the pundits. And yes: even the dogmatically liberal bullies.

As a note: I absolutely don’t think conservatives are, on an individual basis, any better at treating their opponents with dignity and compassion. I can’t help but notice that we live in a world where the journalists, writers, editors, actors, directors, script-writers and–in short–the folks with their hands on the rudder of our culture are extremely socially liberal. In that context, I think conservative commentators face more pressure, especially the kind we don’t see because it comes from their peers in the news/entertainment industry–but I don’t for a second think that Michael Moore or Rachel Maddow have it easy, either.

I haven’t figured out how to reconcile all this love-thy-enemy stuff with my belief that facts matter, that policies are worth debating, and that some ideals and principles the world thinks are dumb are worth standing up for. But I’m working on it. I have this vision in my mind of having genteel adversaries who fight tooth and nail to defeat each other, but who always play within certain rules. And who are able to engage in witty banter, tokens of respect, and maybe even admiration and friendship despite being on opposite sides. Naive and stupid, perhaps, but it’s the best I’ve got. I like the idea that I could throw a party and all my friends would show up–no matter what their politics–and everyone would know they were welcome in my home. I think it’s harder to pull off than that, but like I said: I’m working on it.

So, going back to Ann Coulter one last time, I think partly what happened is that all the crap she has to deal with made her bitter, and that comes out in her writing. I’m not saying she didn’t do anything to bring it upon herself, or that she would be writing nothing but children’s fairytales if only people would be nicer to her. I’m also not saying there isn’t room for biting satire in political discourse: differnet people have different voices and some are going to be more abrasive than others. I don’t think there’s One True Tone for Correct Political Discussion. I just hope to avoid succumbing to bitterness and anger myself, and hopefully not pushing too many people too far in that direction either.