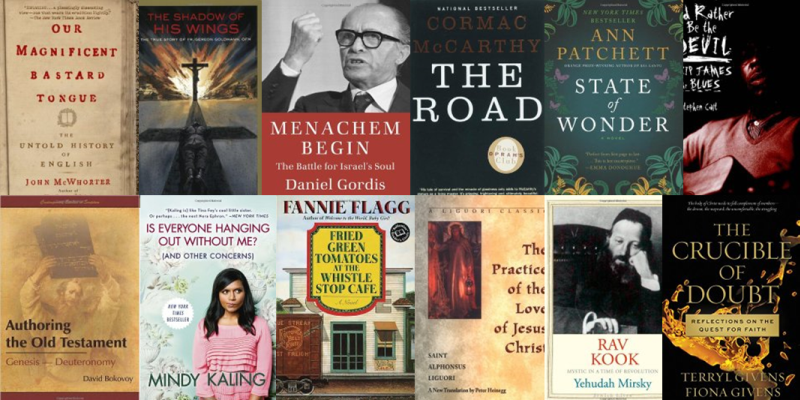

I thought it would be fun to have the DR Editors pick their best reads from 2014. I’m glad I did! Looking through the lists of books and the reviews was really interesting, and it definitely shows what a diverse set of readers[ref]And therefore: of writers.[/ref] we have here at Difficult Run. Without further ado, here are the lists they sent in the order in which they were received.

Monica

Monica emailed me to say “I think I only read 5 or so books in 2014 anyway, and none of them were really remarkable to me. :-/.” Fair enough, and let us all wish Monica better luck in picking books to read in 2015!

Robin Givens

1. Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (And Other Concerns) by Mindy Kaling

by Mindy Kaling

Mindy Kaling gives a voice to all lady craziness. If Tina Fey is my best friend because Liz Lemon is my spirit animal, and if Amy Poehler is my best friend because she’s all girl power, then Mindy Kaling is my best friend because she is a girly-girl (not me, but I appreciate), anxious (me), school nerd (me). This book definitely has a particular audience which is 30-ish females who dare to be non-academic (even if some of them still get straight A’s). Mindy Kaling is a comedian whose voice carries over entirely to the book, something I haven’t found in other comedian memoirs. Also, can Mindy Kaling PLEASE write a YA vampire romance series?!

Mindy Kaling gives a voice to all lady craziness. If Tina Fey is my best friend because Liz Lemon is my spirit animal, and if Amy Poehler is my best friend because she’s all girl power, then Mindy Kaling is my best friend because she is a girly-girl (not me, but I appreciate), anxious (me), school nerd (me). This book definitely has a particular audience which is 30-ish females who dare to be non-academic (even if some of them still get straight A’s). Mindy Kaling is a comedian whose voice carries over entirely to the book, something I haven’t found in other comedian memoirs. Also, can Mindy Kaling PLEASE write a YA vampire romance series?!

I guess I find “Jack and Diane” a little disgusting…I wish there was a song called “Nguyen and Ari,” a little ditty about a hardworking Vietnamese girl who helps her parents with the franchised Holiday Inn they run and does homework in the lobby, and Ari, a hardworking Jewish boy who does volunteer work at his grandmother’s old-age home, and they meet after school at the Princeton Review. They help each other study for the SATs and different AP courses, and then after months of studying, and mountains of flashcards, they kiss chastely upon hearing the news that they both got into their top college choices.”

2. Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe (Ballantine Reader’s Circle) by Fannie Flagg

by Fannie Flagg

I love Southern fiction and I love crazy people, and this book is all about crazy Southern people. This is the kind of quirky Southern fiction that will make you think “I have to stop reading Southern fiction because nothing can ever possibly compare.” There are deep sadnesses, great triumphs, secret collaborations, hilarious anecdotes, kooky characters, ridiculous names, inspiring loves and most of all loyal friendships. Love.

I love Southern fiction and I love crazy people, and this book is all about crazy Southern people. This is the kind of quirky Southern fiction that will make you think “I have to stop reading Southern fiction because nothing can ever possibly compare.” There are deep sadnesses, great triumphs, secret collaborations, hilarious anecdotes, kooky characters, ridiculous names, inspiring loves and most of all loyal friendships. Love.

“By the way, Boots died and Opal says she hopes you’re satisfied.

…Dot Weems…”

3. State of Wonder: A Novel by Patchett, Ann Reprint (2012) Paperback by Ann Patchett

by Ann Patchett

This is a great read for any female in graduate school (but if you’re not in graduate school, it’s still great). Not only is it a mystery/adventure beach read (with a hint of science fiction), but it really explores the mentor-student relationship in all of its (possible) horror. The story is a modern, feminine retelling of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. If you hated that book in high school, you will still like this book. The most interesting things I found with Patchett’s writing are her ability to convey the emotion of a scene through dialogue, and her great use of flashback intertwined with the current moment. I could not put this book down!!

This is a great read for any female in graduate school (but if you’re not in graduate school, it’s still great). Not only is it a mystery/adventure beach read (with a hint of science fiction), but it really explores the mentor-student relationship in all of its (possible) horror. The story is a modern, feminine retelling of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. If you hated that book in high school, you will still like this book. The most interesting things I found with Patchett’s writing are her ability to convey the emotion of a scene through dialogue, and her great use of flashback intertwined with the current moment. I could not put this book down!!

Walker Wright

1. The Crucible of Doubt: Reflections On the Quest for Faith by Terryl & Fiona Givens[ref]Editor’s Note: I was going to pick this one too, but Walker got there first![/ref]

by Terryl & Fiona Givens[ref]Editor’s Note: I was going to pick this one too, but Walker got there first![/ref]

The Givenses’ most recent work is, as Adam Miller put it, “a nearly perfect book.” Many books have been written on the nature of faith and doubt, but none (that I’m aware of) tackle it from a purely Mormon perspective. The LDS faith produces a number of somewhat unique angles and situations for doubt due to its history and theological claims. These include but are not limited to modern prophetic authority and the temptation of hero worship, the Church’s doctrines in relation to other traditions and sources of truth, and the actual role the LDS Church as an organization plays in the world today and in God’s eternal plan. The Givenses provide deep insights, workable paradigms, and new language by which to articulate the messiness of lived religion. In a culture and tradition that paradoxically teaches both progressive learning and religious certainty, this book provides a method of faithful doubting. Questions, as noted recently by President Ucthdorf, led to the Restoration. I hope that this book will begin to erode the cultural stigma toward doubt and help reestablish a culture of consistent seeking.

The Givenses’ most recent work is, as Adam Miller put it, “a nearly perfect book.” Many books have been written on the nature of faith and doubt, but none (that I’m aware of) tackle it from a purely Mormon perspective. The LDS faith produces a number of somewhat unique angles and situations for doubt due to its history and theological claims. These include but are not limited to modern prophetic authority and the temptation of hero worship, the Church’s doctrines in relation to other traditions and sources of truth, and the actual role the LDS Church as an organization plays in the world today and in God’s eternal plan. The Givenses provide deep insights, workable paradigms, and new language by which to articulate the messiness of lived religion. In a culture and tradition that paradoxically teaches both progressive learning and religious certainty, this book provides a method of faithful doubting. Questions, as noted recently by President Ucthdorf, led to the Restoration. I hope that this book will begin to erode the cultural stigma toward doubt and help reestablish a culture of consistent seeking.

2. Women at Church: Magnifying LDS Women’s Local Impact by Neylan McBaine

by Neylan McBaine

Neylan McBaine’s book is both important and timely, offering wisdom and insight for both LDS leaders and lay members. Neylan’s ability to carefully navigate the rather heated and sensitive topic of gender roles within the LDS Church is awe-inspiring. She avoids painting women as victims or overusing buzzwords like “patriarchy,” while still pointedly addressing the sexism that is sometimes (often unintentionally) bred in Mormon culture. Her choice of stories—several from non-American settings–paints a more vivid, diverse picture of the LDS Church and the men and women within it. Neylan’s empathic take on both traditional and more critical LDS views is an excellent example of bridge building and readers will likely be influenced to adopt a more charitable approach to those they disagree with. She largely avoids the theological entanglements of gender essentialism and the like, instead relying on business-oriented studies and material to provide a realistic framework in which actual improvements can be made. The end product is inspiring, thoughtful, and often paradigm-shifting. Every LDS member, as well as outsiders looking in, would benefit from reading it.

Neylan McBaine’s book is both important and timely, offering wisdom and insight for both LDS leaders and lay members. Neylan’s ability to carefully navigate the rather heated and sensitive topic of gender roles within the LDS Church is awe-inspiring. She avoids painting women as victims or overusing buzzwords like “patriarchy,” while still pointedly addressing the sexism that is sometimes (often unintentionally) bred in Mormon culture. Her choice of stories—several from non-American settings–paints a more vivid, diverse picture of the LDS Church and the men and women within it. Neylan’s empathic take on both traditional and more critical LDS views is an excellent example of bridge building and readers will likely be influenced to adopt a more charitable approach to those they disagree with. She largely avoids the theological entanglements of gender essentialism and the like, instead relying on business-oriented studies and material to provide a realistic framework in which actual improvements can be made. The end product is inspiring, thoughtful, and often paradigm-shifting. Every LDS member, as well as outsiders looking in, would benefit from reading it.

3. Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis–Deuteronomy (Paperback) – Common by David E. Bokovoy

by David E. Bokovoy

This book is one that, surprisingly, both LDS and non-LDS alike can benefit from. The book is written as less of an argument (even if the evidence presented within it could be used to bolster an impressive one), but as an invitation. The first five chapters focus on the Documentary Hypothesis, breaking it down in a highly accessible way. The final five focus specifically on Latter-day Saints and their holy books (i.e. the Book of Moses, the Book of Abraham, and the Book of Mormon), providing readers with an informative paradigm by which to approach scripture, revelation, and “translation.” A secularist can find value in Bokovoy’s description of the Book of Moses and Book of Abraham as modern pseudepigrapha, while an apologist will find plenty of material for ancient origins. While there is room for debate regarding David’s approach to restoration scriptures (I tend to take an eclectic approach, seeing it as a mix of pseudepigrapha, midrash, targum, history, and iconotropy), that’s the point: to think critically about these texts. Bokovoy does not offer his view as the final word, but as a possible paradigm. And it is a valuable one at that. David and Greg Kofford Books have done Latter-day Saints a great service with this publication. I hope to see its influence in future Sunday School, Institute, and Seminary classes Church wide.

This book is one that, surprisingly, both LDS and non-LDS alike can benefit from. The book is written as less of an argument (even if the evidence presented within it could be used to bolster an impressive one), but as an invitation. The first five chapters focus on the Documentary Hypothesis, breaking it down in a highly accessible way. The final five focus specifically on Latter-day Saints and their holy books (i.e. the Book of Moses, the Book of Abraham, and the Book of Mormon), providing readers with an informative paradigm by which to approach scripture, revelation, and “translation.” A secularist can find value in Bokovoy’s description of the Book of Moses and Book of Abraham as modern pseudepigrapha, while an apologist will find plenty of material for ancient origins. While there is room for debate regarding David’s approach to restoration scriptures (I tend to take an eclectic approach, seeing it as a mix of pseudepigrapha, midrash, targum, history, and iconotropy), that’s the point: to think critically about these texts. Bokovoy does not offer his view as the final word, but as a possible paradigm. And it is a valuable one at that. David and Greg Kofford Books have done Latter-day Saints a great service with this publication. I hope to see its influence in future Sunday School, Institute, and Seminary classes Church wide.

Honorable Mention:

Letters to a Young Mormon by Adam S. Miller

by Adam S. Miller

For Zion: A Mormon Theology of Hope by Joseph M. Spencer

by Joseph M. Spencer

Allen Hansen

1. Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution (Jewish Lives) by Yehuda Mirsky

by Yehuda Mirsky

I greatly admire the Rav Kook, arguably among the most original and radical religious thinkers of all time, a man who tried to find the spark of holiness in everyone, even in his opponents. Yehuda Mirsky’s new biography traces Kook’s life from his beginnings in the traditional, conservative world of Jewish Eastern Europe to his move to Palestine in 1904 where he attempted to build bridges between that world and the young, free-thinking Zionists. Then came the horrors of the First World War, which Kook saw in starkly religious terms. The rest of the book is taken up with Kook’s return to Palestine under the British, where he became chief rabbi. Mirsky shows how Kook could be theologically bold and psychologically incisive, yet remained politically naïve. At his best, Rabbi Kook could bridge the traditional and modern worlds in a unique, visionary way, and this biography is an excellent introduction to his pivotal impact on Judaism and the Middle East.

I greatly admire the Rav Kook, arguably among the most original and radical religious thinkers of all time, a man who tried to find the spark of holiness in everyone, even in his opponents. Yehuda Mirsky’s new biography traces Kook’s life from his beginnings in the traditional, conservative world of Jewish Eastern Europe to his move to Palestine in 1904 where he attempted to build bridges between that world and the young, free-thinking Zionists. Then came the horrors of the First World War, which Kook saw in starkly religious terms. The rest of the book is taken up with Kook’s return to Palestine under the British, where he became chief rabbi. Mirsky shows how Kook could be theologically bold and psychologically incisive, yet remained politically naïve. At his best, Rabbi Kook could bridge the traditional and modern worlds in a unique, visionary way, and this biography is an excellent introduction to his pivotal impact on Judaism and the Middle East.

2. I’d Rather Be the Devil: Skip James and the Blues by Stephen Calt

by Stephen Calt

Skip James is my favorite bluesman. He was also a pretty appalling individual. What particularly fascinates me is how similar blues culture was to rap culture in many ways. Pimping, getting rich quick, clubbing, and violence, it is all there in the life of Skip James, so he feels surprisingly modern. Stephen Calt was one of the few people whom James considered a friend, and he shared with him many (contradictory) details of his life. Calt traces James’ life from the early 20th century to his rediscovery by white fans in the 1960s. He does so critically, so there is no getting around the fact that despite being gifted, James was also proud, paranoid, and unloving. Calt really has little patience for myth or romanticism. Calt also accepts that not all blues music was good, and shows James’ limitations as a musician. There is also a wealth of historical detail about the south, its dialects, culture and religion. Ultimately, the book is the tragic portrait of an intelligent, undeniably talented man who at the end of his life had nothing to be proud of except performing a song better than Cream’s cover version.

Skip James is my favorite bluesman. He was also a pretty appalling individual. What particularly fascinates me is how similar blues culture was to rap culture in many ways. Pimping, getting rich quick, clubbing, and violence, it is all there in the life of Skip James, so he feels surprisingly modern. Stephen Calt was one of the few people whom James considered a friend, and he shared with him many (contradictory) details of his life. Calt traces James’ life from the early 20th century to his rediscovery by white fans in the 1960s. He does so critically, so there is no getting around the fact that despite being gifted, James was also proud, paranoid, and unloving. Calt really has little patience for myth or romanticism. Calt also accepts that not all blues music was good, and shows James’ limitations as a musician. There is also a wealth of historical detail about the south, its dialects, culture and religion. Ultimately, the book is the tragic portrait of an intelligent, undeniably talented man who at the end of his life had nothing to be proud of except performing a song better than Cream’s cover version.

3. Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel’s Soul (Jewish Encounters) Daniel Gordis

Daniel Gordis

Menachem Begin, Israel’s sixth prime minister, was nothing if not controversial. Begin led the armed insurgency against the British in 1940s Palestine, and was considered by them terrorist No. 1. Begin was publicly denounced by Einstein, and constantly vilified by Ben-Gurion. As prime minister, Begin launched the attack on the Iraqi nuclear reactor, and initiated the First Lebanese War. Yet he also signed the peace treaty with Egypt, and he took in Vietnamese refugees when no one else did. Daniel Gordis does a superb job of putting Begin in context, highlighting how Begin’s profound attachment to his Jewish identity shaped his life and political vision. Gordis brings nuances to the moral dilemmas that Begin faced, and it is hard to walk away from this biography without gaining appreciation for Begin as a person. He made tough decisions, but did not throw anyone under the bus if things went wrong. Given his reputation, it is surprising to learn that he attempted to minimize bloodshed, and was determined to avoid a civil war among the various Jewish factions. Despite his unyielding devotion to the Jewish cause, he also believed in a universal humanism. Gordis’ biography makes it hard to accept the common wisdom which holds that religion and nationalism inevitably have a negative impact on politics. The truth is always far messier and complex.

Menachem Begin, Israel’s sixth prime minister, was nothing if not controversial. Begin led the armed insurgency against the British in 1940s Palestine, and was considered by them terrorist No. 1. Begin was publicly denounced by Einstein, and constantly vilified by Ben-Gurion. As prime minister, Begin launched the attack on the Iraqi nuclear reactor, and initiated the First Lebanese War. Yet he also signed the peace treaty with Egypt, and he took in Vietnamese refugees when no one else did. Daniel Gordis does a superb job of putting Begin in context, highlighting how Begin’s profound attachment to his Jewish identity shaped his life and political vision. Gordis brings nuances to the moral dilemmas that Begin faced, and it is hard to walk away from this biography without gaining appreciation for Begin as a person. He made tough decisions, but did not throw anyone under the bus if things went wrong. Given his reputation, it is surprising to learn that he attempted to minimize bloodshed, and was determined to avoid a civil war among the various Jewish factions. Despite his unyielding devotion to the Jewish cause, he also believed in a universal humanism. Gordis’ biography makes it hard to accept the common wisdom which holds that religion and nationalism inevitably have a negative impact on politics. The truth is always far messier and complex.

Honourable[ref]Editor’s note: I left the spelling intact![/ref] Mention:

Terror Out of Zion: The Fight for Israeli Independence by J. Bowyer Bell

by J. Bowyer Bell

1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War by Benny Morris

by Benny Morris

Bryan Maack

1. The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism by Tim Keller

by Tim Keller

I think people are rightfully calling Tim Keller the new C.S. Lewis. The pastor of a New York Presbyterian Church, he writes in a simple and short yet deeply insightful manner. His book clocks in at 250 pages, but they read easily, and every page has value. His book is broken down into two main parts. First, he covers the arguments against Christianity such as there can’t be one true religion, how a good God could allow suffering, and how science has disproved Christianity. Keller then follows up with reasons for believing in Christianity, such as the famous argument from desire, the clues to God in the human mind and the natural world, the meaning of sin, and much more. He uses citations amply, which provide both credibility and additional reading. Overall, a great book which I can’t do justice to in a short review. Go read it yourself!

I think people are rightfully calling Tim Keller the new C.S. Lewis. The pastor of a New York Presbyterian Church, he writes in a simple and short yet deeply insightful manner. His book clocks in at 250 pages, but they read easily, and every page has value. His book is broken down into two main parts. First, he covers the arguments against Christianity such as there can’t be one true religion, how a good God could allow suffering, and how science has disproved Christianity. Keller then follows up with reasons for believing in Christianity, such as the famous argument from desire, the clues to God in the human mind and the natural world, the meaning of sin, and much more. He uses citations amply, which provide both credibility and additional reading. Overall, a great book which I can’t do justice to in a short review. Go read it yourself!

2. The Shadow of His Wings: The True Story of Fr. Gereon Goldmann, OFM by Gereon Goldmann

by Gereon Goldmann

Gereon Goldmann recalls his harrowing years up to and during WW2 as a Catholic priest-in-training who was drafted into the SS as a medic before he could finish his theological training. His autobiography paints a picture of one man, trusting in God, trying to stay alive and faithful to his beliefs through the trials of World War 2. The book reads like ‘based on a true story’ and yet *is* a true story. Goldmann defies the SS straight to their face. He meets with Pope Pius XII during the war and become a priest despite lacking years of training. He carries the Eucharist throughout the war, ministering to the fearful and dying, and at one point wades across a river above his head with only the Eucharist above water in his hand, hoping nearby British sentries don’t notice the mysterious Eucharist container moving across the river. He ends up in a French prison camp in the middle of the desert after the war with a bunch of Nazis who refuse to give up, and through faithful dedication overthrows their de facto ownership of the camp despite attempts on his life. Goldmann survives all of these ordeals and ultimately becomes a missionary to Japan! I truly have found few biographies more inspiring than Father Goldmann’s.

Gereon Goldmann recalls his harrowing years up to and during WW2 as a Catholic priest-in-training who was drafted into the SS as a medic before he could finish his theological training. His autobiography paints a picture of one man, trusting in God, trying to stay alive and faithful to his beliefs through the trials of World War 2. The book reads like ‘based on a true story’ and yet *is* a true story. Goldmann defies the SS straight to their face. He meets with Pope Pius XII during the war and become a priest despite lacking years of training. He carries the Eucharist throughout the war, ministering to the fearful and dying, and at one point wades across a river above his head with only the Eucharist above water in his hand, hoping nearby British sentries don’t notice the mysterious Eucharist container moving across the river. He ends up in a French prison camp in the middle of the desert after the war with a bunch of Nazis who refuse to give up, and through faithful dedication overthrows their de facto ownership of the camp despite attempts on his life. Goldmann survives all of these ordeals and ultimately becomes a missionary to Japan! I truly have found few biographies more inspiring than Father Goldmann’s.

3. The Practice of the Love of Jesus Christ (A Liguori Classic) by Saint Alphonsus Liguori

by Saint Alphonsus Liguori

Saint Liguori set out in the mid 1700s to write a book for the poor and uneducated of Italy about the love of Jesus Christ. I love this book precisely because it is written for the simple and uneducated. I want to be taught as one would teach a peasant, starting with the simplest concepts, because I have found often that in simplicity there is the genuine love of Christ so often lacking in complex treatises. Saint Liguori pulls liberally from scripture and from other Catholic saints to teach us how much Jesus has done for us, and in return how we can best love Jesus. “For my part, I know of no other perfection than that of loving God with all the heart, because without love all the other virtues are nothing but a pile of stones.”

Saint Liguori set out in the mid 1700s to write a book for the poor and uneducated of Italy about the love of Jesus Christ. I love this book precisely because it is written for the simple and uneducated. I want to be taught as one would teach a peasant, starting with the simplest concepts, because I have found often that in simplicity there is the genuine love of Christ so often lacking in complex treatises. Saint Liguori pulls liberally from scripture and from other Catholic saints to teach us how much Jesus has done for us, and in return how we can best love Jesus. “For my part, I know of no other perfection than that of loving God with all the heart, because without love all the other virtues are nothing but a pile of stones.”

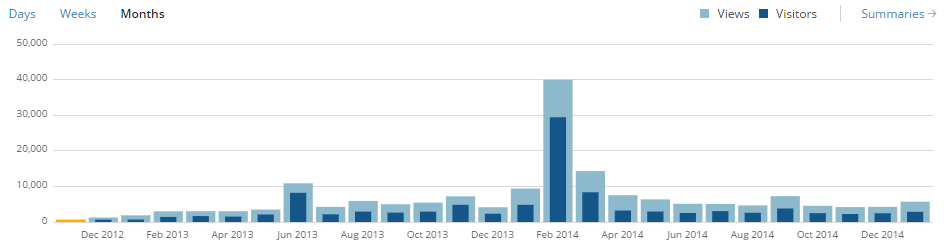

Nathaniel Givens

I read a lot of books in 2014 (more than 60), so picking just the top three is going to be tricky. Here we go.

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt

by Jonathan Haidt

I put off reading The Righteous Mind for a while not because I wasn’t sure if it would be good or not, but because I was sure that it would be good. I was already familiar from interviews, articles, and videos with both Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory and its basic political implications. I thought it was fascinating and compelling theory, and I assumed that this book–like so many popular non-fiction books–would be a couple of hundred pages of fluff around a core idea that could be expressed in 70 pages or less. When I actually read the book, however, I was shocked and surprised to see how wrong I’d been.

I put off reading The Righteous Mind for a while not because I wasn’t sure if it would be good or not, but because I was sure that it would be good. I was already familiar from interviews, articles, and videos with both Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory and its basic political implications. I thought it was fascinating and compelling theory, and I assumed that this book–like so many popular non-fiction books–would be a couple of hundred pages of fluff around a core idea that could be expressed in 70 pages or less. When I actually read the book, however, I was shocked and surprised to see how wrong I’d been.

There’s a lot more going on in this book than Moral Foundations Theory. There is MFT, of course, but it’s very interesting to see Jonathan Haidt put it in its historical context by writing of his own coming-of-age (as a researcher) narrative. Then, going far beyond MFT, there’s just a lot of really, really excellent discussion of the basics of human nature. There are two core ideas, and both of them are starkly post-post-modern (as N. T. Wright would say). The first critiques the model of human nature that pictures us as more or less rational and more or less monolithic. Instead, Haidt uses the metaphor of an elephant (our emotional and psychological behaviors) with a rider perched on top (our rational mind) where the rider has very limited control over the elephant and acts more as a PR firm to justify what the elephant does rather than an expert consultant to guide its behavior.[ref]Haidt is explicitly Humean in his outlook on human nature, so now I know I’m not the only one![/ref] The second critiques the idea of human individualism, pointing out that we are (as Haidt metaphorically puts it) 90% chimp and 10% honeybee. We have a “hive switch” that, when activated by various group religious, cultural, or military behaviors, turns a bunch of individuals into a single, cohesive whole. Taken together, these two ideas constitute one of the most important attacks on the core Enlightenment philosophical tenets that have survived into modernity[ref] And, citing N. T. Wright again, which turn out to be a retread of Epicureanism rather than a genuinely modern innovation.[/ref], although that observation goes beyond what Haidt himself has to say. The book is fascinating, compelling, and deeply relevant to our world today.

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

by Cormac McCarthy

This is one of those books that has had a tremendous amount of positive buzz, and I was really happy that it lived up to all the good rumors I’d heard. I classify this as a work of genuinely literary sci-fi, along with books like Never Let Me Go

This is one of those books that has had a tremendous amount of positive buzz, and I was really happy that it lived up to all the good rumors I’d heard. I classify this as a work of genuinely literary sci-fi, along with books like Never Let Me Go or The Handmaid’s Tale

or The Handmaid’s Tale : they come from outside the stable of authors traditionally considered to be genre writers in the sci-fi tradition, but they are books that absolutely couldn’t exist without the concepts and tropes popularized by sci-fi genre writers. They are sort of the best of both worlds: more emphasis on prose and characterization than you sometimes get from books shelved in the sci-fi section, but with that genuine spark of inquisitiveness and analysis that is the hallmark of “the literature of ideas.” In particular, The Road is a literary take on the post-apocalyptic sub-genre that simultaneously uses the apocalypse as a backdrop for an introspective father/son story (sort of a mirror image coming-of-age story, where the boy comes of age almost without the father realizing what is happening) but at the same time treats the backdrop seriously and as more than a mere prop. This is why, I think, it can satisfy both hard core sci-fi fans and also those who have never really gotten into the genre. I will add that I couldn’t fully enjoy the book as I read it through the first time because ever since I’ve had kids of my own I can’t really deal with traumatic things happening to children in fiction, and I wasn’t sure how dark this book was going to get. I won’t give any spoilers other than to say the ending wasn’t what I expected, but it worked fantastically. I want to reread this one again some day.

: they come from outside the stable of authors traditionally considered to be genre writers in the sci-fi tradition, but they are books that absolutely couldn’t exist without the concepts and tropes popularized by sci-fi genre writers. They are sort of the best of both worlds: more emphasis on prose and characterization than you sometimes get from books shelved in the sci-fi section, but with that genuine spark of inquisitiveness and analysis that is the hallmark of “the literature of ideas.” In particular, The Road is a literary take on the post-apocalyptic sub-genre that simultaneously uses the apocalypse as a backdrop for an introspective father/son story (sort of a mirror image coming-of-age story, where the boy comes of age almost without the father realizing what is happening) but at the same time treats the backdrop seriously and as more than a mere prop. This is why, I think, it can satisfy both hard core sci-fi fans and also those who have never really gotten into the genre. I will add that I couldn’t fully enjoy the book as I read it through the first time because ever since I’ve had kids of my own I can’t really deal with traumatic things happening to children in fiction, and I wasn’t sure how dark this book was going to get. I won’t give any spoilers other than to say the ending wasn’t what I expected, but it worked fantastically. I want to reread this one again some day.

Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English by John McWhorter

by John McWhorter

On one level, this is a book-length exposition of McWhorter’s theory of where the English language came from, written for a layperson to understand. But with this book, the journey is at least as valuable as the destination. By the time he got to his big reveal at the end, I had completely forgotten that that was the point of the book. I was simply too fascinated by his explanation of the linguistic history of English, especially as it related to the political and cultural history of Europe. But then when he did pull it all together in the end, I was excited by his theory, too. It gave the book the feel of an exciting techno-mystery where there’s some ancient, unexplained clue that–once it is unraveled–gives us fresh insight into the past. I’m definitely a huge fan of McWhorter, and I have to stress that if you’re not listening to the audiobook versions of his books (which he narrates himself), you’re missing out. With linguistics as with no other subject, there is really no substitute for the spoken word.

On one level, this is a book-length exposition of McWhorter’s theory of where the English language came from, written for a layperson to understand. But with this book, the journey is at least as valuable as the destination. By the time he got to his big reveal at the end, I had completely forgotten that that was the point of the book. I was simply too fascinated by his explanation of the linguistic history of English, especially as it related to the political and cultural history of Europe. But then when he did pull it all together in the end, I was excited by his theory, too. It gave the book the feel of an exciting techno-mystery where there’s some ancient, unexplained clue that–once it is unraveled–gives us fresh insight into the past. I’m definitely a huge fan of McWhorter, and I have to stress that if you’re not listening to the audiobook versions of his books (which he narrates himself), you’re missing out. With linguistics as with no other subject, there is really no substitute for the spoken word.

Honorable Mention:

Gilead: A Novel by Marilynne Robinson

by Marilynne Robinson

What It Is Like To Go To War by Karl Marlantes

by Karl Marlantes

Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said by Philip K. Dick

by Philip K. Dick

Mother Night: A Novel by Kurt Vonnegut

by Kurt Vonnegut