This post is part of the General Conference Odyssey.

The talk that struck me the most this week was Elder A. Theodore Tuttle’s The Things that Matter Most. He began his talk with an excerpt from a Deseret News article about how racing greyhounds, which are trained to chase a fake rabbit around the track, don’t even know what a real rabbit looks like. According to the editorial Elder Tuttle quoted:

We chase social pleasures on a glittering noisy treadmill—and ignore the privilege of a quiet hour telling bedtime stories to an innocent-eyed child. We chase prestige and wealth, and don’t recognize the real opportunities for joy that cross our paths.

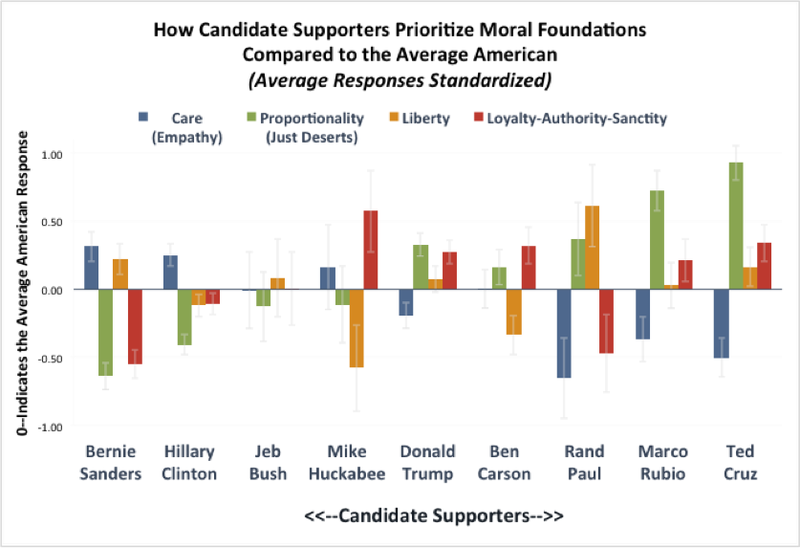

This immediately reminded me of Jonathan Haidt’s book The Happiness Hypothesis. In the book, Haidt—a social psychologist we often cite here at Difficult Run because of his work on Moral Foundations Theory—distills important lessons from a variety of world philosophies through the lens of psychology. According to Haidt (writing in a followup book), “One of the greatest truths in psychology is that the mind is divided into parts that sometimes conflict.”

In The Happiness Hypothesis, Haidt talks about the rider (the conscious, deliberate, rational side of our minds) and the elephant (the intuitive and emotional side of our minds). As an intuitionist, Haidt puts a lot of emphasis on the intuitive sides of our nature (the elephant). He underscores how important our intuition is (even to logical, analytical thinking) and also highlights how sophisticated our intuitive natures are. However, there are drawbacks, one of the most important of which is this:

The elephant cares about prestige, not happiness, and it looks eternally to others to figure out what is prestigious. The elephant will pursue its evolutionary goals even when greater happiness can be found elsewhere.

The elephant is the product of evolution and natural selection. It cares about prestige because status—in primates—is what provides access to reproduction. It doesn’t care about happiness or fulfillment because happiness and fulfillment are, from a genetic perspective, kind of beside the point. This is why the pursuit of prestige—nice job, nice car, nice house—is so irresistible. It’s embedded in our biological natures. And it’s a treacherous trap, as Haidt points out, because pursuit of prestige is always a zero-sum game.

If everyone is chasing the same limited amount of prestige, then all are stuck in a zero-sum game, an eternal arms race, a world in which rising wealth does not bring rising happiness. The pursuit of luxury goods is a happiness trap; it is a dead end that people raced toward the mistaken belief that it will make them happy.

Sound familiar?

Elder Tuttle then points out that the people who are most vulnerable to being trampled when our inner elephant charges off in search of status and prestige are the people we care about the most:

Our most flagrant violations, perhaps, occur in our own homes. We chase worldly pleasures and neglect our own innocent children. When did you tell stories to your children?

Every single night I pray for help in resisting this. When you’re a parent, the days crawl and the years fly. Children are miracles from God, but—like many of God’s greatest miracles—they are in danger of being overlooked and neglected.

On Sunday I taught Gospel Doctrine and we focused on the murmurings of Laman and Lemuel in chapters 16 – 18. For the first time, I noticed a very definite pattern in the slow hardening of the hearts. At first, in chapter 16, all it took was a lecture from Nephi to bring them to repentance. Later, when Nephi’s bow broke, it took the indirect voice of the Lord (through the Liahona) to bring them to their sesnse. Later, when Ishmael died, the voice of the Lord directly was required. Finally, when Nephi started to build a ship, it took a threat of physical violence to humble them. The problem wasn’t that Laman and Lemuel murmured. Everyone murmurs. It’s that their hearts grew harder with every passing trial.

But when the penultimate confrontation came it wasn’t a result of trial or tribulation. The argument that prompted Laman and Lemuel to tie Nephi to the mast of their ship for days wasn’t the result of hardship. The spark that started that fire happened when things were going well. The ship was built, the supplies were loaded, the journey was easy, and there was no hard work to do. And that was when the greatest crisis erupted. Which explains why Elder Tuttle writes:

The trials through which today’s young people are passing—ease and luxury—may be the most severe test of any age. Brothers and sisters, stay close to your own! Guide them safely! These are perilous times. Give increased attention. Give increased effort.

You want a simple example of this? Screen-time is the easiest. Don’t get me wrong, we’re not one of those families with no TV and no screens. My wife is getting her PhD in computer science and my job is in software development. My kids are expert Minecraft players and I enjoy playing Castle Crashers with them. We’ve watched Avatar: The Last Airbender all the way through twice and started it a third time. So screens can be—and are—a part of this family. But they’re also perilous. The older your kids get, the easier it is to tell them to leave you alone and have them actually do it. An infant can’t leave you alone. A toddler can sometimes, but only for a few minutes. But a 9-year old is perfectly capable of entertaining him or herself for a few hours or more. Throw in a TV or a video game console or an iPhone and you could—if you wanted—basically live in the same house as your children and never really interact with them.

That is the peril—for them and for you—of “ease and luxury.” As a parent, I have learned that the greatest tragedy is not that your kids don’t listen to you. It’s that they do. If they hear “I’m busy” often enough, or “Daddy doesn’t have time” frequently enough, the message does sink in, and then there’s no way to take it back.

These are indeed perilous times. Growth is always risky. It is always perilous as your children grow more independent and begin to take on more and more freedom for themselves. But that ordinary course of getting older is even more perilous in our society, which makes it so easy to curate digital connections and so easy to forget the flesh-and-blood variety.

And finally there is this:

The responsibility rests on the family to solve our social problems. Youth search for security. They search for answers to be found only in a good home. No national or international treaty can bring peace. Not in legislative halls nor judicial courts will our problems be solved. From the hearthstones of the homes will come the answers to our problems. On the principles taught by the Savior, happiness and peace will come to families. In the home youth will receive strength to find happiness.

As I wrote about last week, I believe this to be entirely literal. Laws and governments are a superficial veneer on society. They are important, but they are not essential. What matters more than formal institutions are the informal ones: friendships, associations, churches, clubs and—far, far and away the most important—families. This is born out be reams of social science research (another topic we cover at Difficult Run, especially Walker Wright) which underscores the empirically validated truth that stable families are the most important ingredient for stable, prosperous, safe, flourishing, happy societies. It’s not rhetoric and it’s not exaggeration. It’s the truth: the family is the one and only solution to our deepest social problems.

The world doesn’t believe this. “The world is full of foolish schemes.” Many of these schemes are attempts to root a stable society in some foundation other than families. They will not work, and—to the extent that they lead people to turn their attention away from the life-long endeavor of nurturing families—they will lead to unhappiness and suffering.

What is wanted, first and foremost, is true motherhood and true fatherhood. And, as Elder Tuttle writes, we must “face the fact that true fatherhood and true motherhood are fast disappearing.”

He doesn’t spend as much time talking about what those concepts mean. I think the world continues to have a relatively robust account of what true motherhood is about. We continue to understand, to a greater degree than with fatherhood, the dignity and importance of mothers who nourish, protect and care for their children. But fathers—especially if you judge by the bungling, incompetent depictions in popular television—are viewed more and more as auxiliary and disposable. In contrast, Elder Tuttle describes true fatherhood this way:

Fatherhood is a relationship of love and understanding. It is strength and manliness and honor. It is power and action. It is counsel and instruction. Fatherhood is to be one with your own. It is authority and example.

The line that speaks the most to me there is that “Fatherhood is to be one with your own.” I haven’t finished processing it, but it continues to resonate long after I first read it, a bell reverberating on and on in my heart, and calling attention to a message I haven’t fully received yet.

I have learned, in my marriage and in my parenting, that the messages I’ve been taught by the world about being a husband and a father range from irrelevant to insidious. I’m still learning to sift the true meaning of fatherhood from the surrounding chaff. I don’t have it all figured out, but talks like this encourage me to keep going and help guide me along my way.

—

Here are the other posts from the General Conference Odyssey this week:

One of the most surprising things about Cixin Liu’s award-winning science fiction novel The Three-Body Problem

was its direct and unflinching portrayal of China’s Cultural Revolution. The descriptions of bloody civil war and widespread oppression of academic intellectuals was not what I expected from a novel that was first published in China, and the specific dialogue as student protesters harangued a physics professor for daring to teach special relativity was at once chilling and fascinating. In some ways, there are elements of the excellent sequel (The Dark Forest

) that are even more haunting. The way that an author who is so willing to stare the political doublethink of the Cultural Revolution directly in the face has no qualms about positively describing the important role that political officers would play in a modern (presumably less totalitarian) Chinese military shows, to me, how deeply embedded some of the assumptions that led to the Cultural Revolution still remain. So many things that do not seem political to use are that way purely because nobody has bothered to politicize them. But physics, like anything else, can be and has been politicized.

The gospel is freely available to all, including and especially those whose sins may be more public and legally troublesome. They are not truly lost: they can make it back from where they are. But they cannot and should not do it

The gospel is freely available to all, including and especially those whose sins may be more public and legally troublesome. They are not truly lost: they can make it back from where they are. But they cannot and should not do it

Vox has a

Vox has a

The process doesn’t just help the inmates to grow. It can also help the survivors.” Prisoners go through “an intensive, yearlong program designed to help them open up, learn to trust each other, and take greater responsibility for the harm they’ve caused. They explored how crime impacts everyone—not just the direct victims, but the victims’ spouses, children, parents, and communities—while developing empathy for victims through directed exercises. They also learned about the effects of childhood trauma and abuse and how these experiences may have impacted their personal psychology, all the while developing skills like emotional regulation and anger/stress management.” In 1997, “the San Francisco County Sheriff’s Department ordered Washington into a jail program called RSVP:

The process doesn’t just help the inmates to grow. It can also help the survivors.” Prisoners go through “an intensive, yearlong program designed to help them open up, learn to trust each other, and take greater responsibility for the harm they’ve caused. They explored how crime impacts everyone—not just the direct victims, but the victims’ spouses, children, parents, and communities—while developing empathy for victims through directed exercises. They also learned about the effects of childhood trauma and abuse and how these experiences may have impacted their personal psychology, all the while developing skills like emotional regulation and anger/stress management.” In 1997, “the San Francisco County Sheriff’s Department ordered Washington into a jail program called RSVP: