So this exists. And the world is better for it.

Music

A New Spin on “Smells Like Teen Spirit”

So, this is awesome:

[BYU grad] Rob Gardner of “Lamb of God” fame has come together with two friends for a new project with a focus on covering iconic pop songs with a full orchestra, a choir and soloists. Gardner arranged the pieces and co-produced the project with long-time friends and collaborators, brothers Drex and McKane Davis…The project is called Cinematic Pop, and its purpose is cover well-known and popular songs using a cinematic orchestral medium to rekindle an appreciation for the value of orchestral music, both in general and especially with younger generations. “One of our goals and passions for this project is to it bring young people, to get them excited about symphonic music, orchestral music,” Davis said. “Attendance to symphonies across the nation has been decreasing over the years, so to be able to bring the younger generation to that music and introduce it in a creative and impactful way is something that is really core to what we’re doing.” …At this point, the producers plan to release 10 videos total, but the project doesn’t end with the videos. Davis said they all feel passionate about the power of experiencing live music, and they plan to take the show on the road.

Here is their version of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit“:

Why I Don’t Trust Modern Art or Professional Philosophers

There was an article in the New Yorker last month called The Square that pretty well encapsulates why I am deeply suspicious of both modern art and professional philosophers. The eponymous painting is above. A sample of the text follows:

In 1913, or 1914, or maybe 1915—the exact date is unknown—Kazimir Malevich, a Russian painter of Polish descent, took a medium-sized canvas (79.5 cm. x 79.5 cm.), painted it white around the edges, and daubed the middle with thick black paint. Any child could have performed this simple task, although perhaps children lack the patience to fill such a large section with the same color. This kind of work could have been performed by any draftsman—and Malevich worked as one in his youth—but most draftsmen are not interested in such simple forms. A painting like this could have been drawn by a mentally disturbed person, but it wasn’t, and had it been it’s doubtful that it would have had the chance to be exhibited at the right place and at the right time.

After completing this simple task, Malevich became the author of the most famous, most enigmatic, and most frightening painting known to man: “The Black Square.” With an easy flick of the wrist, he once and for all drew an uncrossable line that demarcated the chasm between old art and new art, between a man and his shadow, between a rose and a casket, between life and death, between God and the Devil. In his own words, he reduced everything to the “zero of form.” Zero, for some reason, turned out to be a square, and this simple discovery is one of the most frightening events in art in all of its history of existence.

Here is what irks me: the painting only works within the context of a bunch of fairly esoteric and inside-baseball talk. The picture, itself, represents nothing. It means nothing. It is, more or less, nothing. Not in some pseudoprofound “Zero, for some reason, turned out be a square” nonsense, but in the mundane, “not much to see here” sense.

I suppose you could argue that it’s a matter of taste, and I’m sure to some extent that is true. Some people like art that speaks to them. Others, for whatever reason, prefer art that requires a thesis-worth of material outside the work in question to be able to find a voice. Call me a grouchy old man, but if you listen to a section of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana or stand before a Gothic cathedral or stare up at the Sistine Chapel, you’re going to feel something. You might feel much more if you are a musician, or an art historian, or an architect, but just anybody is going to feel something. [ref]Carmina Burana was finished in 1936, by the way, so I’m not just fetishizing old stuff.[/ref]

And that is what I fundamentally don’t like about modern art. Or about professional philosophers. They are elitist to the point of nihilism. They are belligerent and arrogant in their intentional impenetrability. They are fundamentally hostile to the everyman. And, quite frankly, ain’t nobody got time for that. Give me art, any day of the week, that is actually trying to communicate something to me as I am. Not that is intentionally whispering to only a chosen, select few. Even if I can hear, I have no interest in being part of that anti-humane snobbery.

Ed Sheeran’s “Bloodstream” feat. Ray Liotta

I don’t typically do music videos. I’m not even an Ed Sheeran fan. But his new video for “Bloodstream” features some great acting by a 60-year-old Ray Liotta. The performance is absolutely heartwrenching. Check it out below.

Preview Dustin Kensrue’s New Track

Thrice is my favorite band, and Dustin Kensrue is the reason why. His songwriting and lyrics are incredible. He’s already put out a couple of solo albums, starting with Please Come Home and followed up by a Christmas album and a praise album. Neither one of those was really my thing, but I’m thrilled that he’s coming out with another solo album in April: Carry the Fire. And you want to know what’s even more exciting? You can already listen to one of the songs: “Back to Back”.

This is what Kensrue had to say to Billboard about the album, by the way:

Much of our experience in this life is defined by some degree of suffering. Because of this, sometimes to love someone well means simply sitting with them in their suffering, entering into that suffering with them without offering hollow aphorisms, minimizations, or easy fixes. And this is true in the big things as well as the seemingly small. Whether someone didn’t get the job they were hoping for or whether they just found out they have three months to live, our love is truly shown as we weep with those that weep.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is why I love Mr. Kensrue.

Hearing What They Hear

One of my very favorite parts of the New Year’s season are all the best-of lists that start to come out and especially best albums of 2014. I’m going through the Washington Post’s top 50 albums of 2014 list right now, starting with Montevallo by Sam Hunt (which they put at #2 for the year). I was surprised to find out that I’d already heard one of those songs (“Leave the Night On”), but pop-country is very much not my usual fare so this is definitely a different album from what I usually listen to.

Which is why I like it.

Sure, one of the main reasons I go through these lists is that I’m hoping to find something new that will really speak to me.[ref]Most recent find, if you’re curious, is twenty | one | pilots, which my brother told me to listen to. And now I have to stop myself from just listening to “Migraine” on repeat.[/ref] But the truth is that a lot of the time I like listening to songs that other people like, even if they don’t really speak to me in the same way, because I want to try and hear what they hear.

At one level, it’s just math. The more genres you have acquired a taste for, the more great music there is in your world. But it goes beyond that. You do yourself a favor expanding your capacity to appreciate and your potential to empathize, and in my experience you lose nothing of your own individual perspective along the way. I’m not saying every artist is equally talented or that popularity is quality. Just pointing out that there are a lot of people out there, trying to find or make something beautiful or inspiring or soothing or powerful. If you feel like your world could use a little more of those things, then try stretching out its horizons a little.

Even when you don’t find a new favorite artist, just realizing that other people are trying to bring more light or meaning or fun into the world can bring a sense of hope and optimism. Listening to new genres of music until the sounds and the lyrics start to make some sense is a way of reminding yourself how much we have in common, even when we don’t see eye-to-eye.

And, since I mentioned my current addiction, I’ll give you a sample. I totally didn’t get these guys at first,[ref]I made fun of one of their songs here at Difficult Run before I got into them.[/ref] but now that I’m dialed in to their frequency I can’t listen to their songs without cranking the volume and, more often than not, singing / screaming along.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4-Wvg4OsaA

If the suicide theme seems dark, by the way, be sure you pay attention to the lyrics of the song towards the very end.

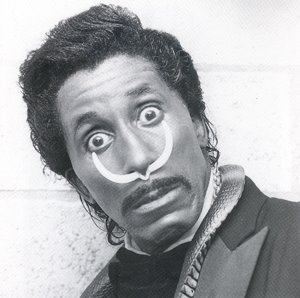

I Put a Spell on You: Remembering Screamin’ Jay Hawkins

Since Halloween is almost here, it is worth remembering one of the truly original weirdos- Screamin’ Jay Hawkins.

Possibly the only person to be equally detested by civil rights groups and the American Casket Association, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins would make his entrance onstage as a witch doctor springing out of a casket. His demented laughter and howls even sent some of his audience running for the doors!

Still, there (sometimes) was more to Hawkins’ music than macabre gimmickry. If you don’t believe me, have another listen to CCR or Nina Simone performing I Put a Spell on You.

Head over to Biography and check out the fun post on Hawkins’ life.

Why I Like Good Guys

That’s Michael Carpenter.[ref]Image by zmajtolovaj.[/ref] Michael Carpenter is my favorite character in the Dresden Files, which is my favorite series. He’s a Knight of the Cross, which means he’s one of three mortals chosen to wield one of the Swords of the Cross, each of which contains a nail from the Crucifixion. They oppose the Denarians–basically fallen angels–although their main job isn’t to conquer the Denarians, it’s to try and rescue humans that the Denarians trick and enslave to their will. Along the way, however, Michael can and does do battle with vampires, dragons, and any other force of darkness that threatens to harm the innocent.

All of that is pretty cool, but none of it gets to the heart of why I like Michael so much. I like him because he’s a devout Catholic. Because he’s a faithful husband. Because he’s a loving father. Because he doesn’t lie or curse, and because he is, in the end, a humble man who just wants to do the right thing because he sincerely trusts and loves his God and his neighbor. He is, in short, a goody-goody.

This type of hero is very rare. Outside of children’s literature (Narnia, or The Dark is Rising, or Harry Potter) and comic books (Superman or Captain America) this kind of hero is basically non-existent. In fact, the piece to which this post is a followup included a link to an article complaining that Captain America “is only interesting if he’s a prick.” Nice guys finish last in more ways than one, it would seem.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying every hero should be a Boy Scout. Where would the world be without scoundrels and rogues? I’m not arguing against Han Solo and Malcom Reynolds!

Walker also wrote a great followup to my initial post called “Darker, Dearie. Much Darker”: Why I Don’t Like “Nice” Heroes in which he said:

I can connect with those who have fallen. I can root for them to repent, to be reconciled with friends and family, and to be forgiven. I personally connect with those who need redemption more than those who don’t seem to need it at all.

Walker’s absolutely right: the redemption narrative is a powerful one. So this post isn’t meant to contradict Walker’s piece. It’s just an alternative or a supplement. It explains why, for all the allure of the anti-hero in need of redemption or the scoundrel with no interest in being saved, my favorite heroes are the white knights.

Let me start with a technical note, however. In Western culture, plot is conflict-driven. This is such a deep cultural assumption that it’s one of those assumptions you don’t even know is an assumption until someone comes along and shows you that there are alternative ways of doing things. Does a fish know what “wet” means? Nope, not unless it has survived a stay on dry land and learned by contrast to understand the nature of its own existence. So it is with conflict-centric plot. If you don’t see an alternative, you don’t even know it’s what you’re swimming in.

Let me start with a technical note, however. In Western culture, plot is conflict-driven. This is such a deep cultural assumption that it’s one of those assumptions you don’t even know is an assumption until someone comes along and shows you that there are alternative ways of doing things. Does a fish know what “wet” means? Nope, not unless it has survived a stay on dry land and learned by contrast to understand the nature of its own existence. So it is with conflict-centric plot. If you don’t see an alternative, you don’t even know it’s what you’re swimming in.

So, as a comparison, I offer up kishōtenketsu which “describes the structure and development of classic Chinese, Korean and Japanese narratives.” There’s 4-panel comic at left as an example: it has plot, but no conflict. [ref]I got that comic from this post, which is well worth the read.[/ref]

The connection between conflict-driven plot and white knights is simple: you don’t necessarily need for your hero to make mistakes, but it certainly makes creating and sustaining conflict easier when they do. This means that Western literature is structurally biased against simplistic good guys. They aren’t impossible to work with, but they are–all else equal–a bit harder to handle.

I don’t think that this fully explains the dearth of goody-goody heroes, however. The same argument that suggests we need morally deficient heroes (to make questionable decisions and fuel conflict) suggests that we need intellectually deficient heroes (to make decisions that are questionable in a different sense of the word), and yet we manage to have intelligent heroes more often than white knights.

Rather than speculate on why our society seems to discredit good guys, however, I just want to say a bit about why I like them.

First of all: I can identify with them. Stick with me for a bit, however, because this might not be going in the direction that you think it is.

I’m the kind of person that people look at and generally think of as an annoying goody-goody.[ref]People who aren’t my fellow Mormons, btw. As a Mormon, I don’t stick out.[/ref] I’m deeply religious, I’ve never had alcohol, smoked a cigarette, or done any other drug (other than for surgery). I waited until marriage for sex. I don’t watch porn. And I’m fully aware that the way people react to a list of statements like that is some combination of disgust at my self-righteousness and pity for my repressiveness. In short: I’m unpopular in the same way and for the same reasons that straight-arrow heroes are unpopular.[ref]In one memorable example a friend asked for my advice on a moral question, I gave a very mild but honest response, and his response was “You really have a way of making people feel like s**t.” Sorry, bro, what do you want me to say? I only suggested you should stop cheating on your girlfriend. I didn’t even bring up waiting until marriage…[/ref]

The important thing is that I identify with the way other people dislike the Boy Scout, but I don’t in any way identify with being morally superior, because I’m acutely aware that I’m not. Sure, I’ve never done drugs, but folks like John Scalzi rarely drink not as a matter of moral principle but because they don’t like to experience a loss of control. That’s not a moral decision one way or the other; it’s a combination of a personal preference and self-preservation. And the reality is that a lot of the vices that I avoided, I avoided for the same reason: personal preference and/or risk avoidance. Sometimes I chose not to do things not because I had such great principles, but because I was scared to do them. That’s not very heroic.

Motivations are complicated things. Sometimes I want to be moral because I want people to trust me and because I want to maintain a favorable self-image. So the moral action can be motivated by selfishness and hedonism. Sometimes I want to avoid destructive addictions because I want my children to have a happy home and stable family. So self-interest can be altruistic as well. I can’t figure out my own motives, so how could I presume to know anyone else’s?

I also realize that I’ve been very lucky. I come from a good, stable home with parents who taught me well and modeled good behavior in their own lives. I didn’t suffer any of the tragedies and hardships that so can damage innocent people and lead them to make bad decisions of their own. I know from research and second-hand experience that these kinds of tragedies are horrifically common. I was just lucky.[ref]I was primarily lucky in the sense of having great parents. They worked hard and sacrificed a lot to give me these advantages.[/ref] The safety, training, and support I received came to me through no merit or choice of my own. There’s no credit in that, either.

So when I see a good guy on screen or in a book who colors mostly inside the lines, I empathize with them. I know that they will appear boring, self-righteous, and shallow to a lot of people because that’s how I come across to a lot of people. I also assume that they have complex reasons for their behavior that are not always good reasons. And so I tend to identify with them both as someone the world often thinks is weird and as someone who has their own struggles and failings to deal with, even if they are sometimes more internal.

That’s another technical point, by the way. Characters who struggle a lot internally don’t often convey well on-screen. So the bias against goody-goodies is strongest in television and movies, and a little bit weaker in books that have a chance to get inside the character’s head.

The thing is, everyone who tries to do the right thing struggles. In the Dresden Files the main character is Harry Dresden. He’s an orphan who was abused as a kid and who–partially based on personality and partially based on his experiences–has serious authority issues, unreasonable levels of petty stubbornness, and a predilection for anger and violence. He struggles all the time with his demons, and sometime he loses and the result is kicking off a supernatural war.[ref]See? Bad decisions fuel conflict-driven plots.[/ref] If you just glance at Michael Carpenter, he always seems to make the right call. But if you look again you can see that it’s not easy for him. He’s doesn’t mindlessly follow the rules without any quibbles. He has to make his own decision about how to interpret them, how far to bend them, and when to follow them even though it puts him or even his family at risk. He deals with ambiguity and guilt and shame and sacrifice, too.[ref]The fact that Jim Butcher created an overtly religious Boy Scout and didn’t turn him into a self-righteous jerk was one of the first things that really made me start taking the Dresden Files seriously.[/ref]

So part of what I’m getting at is simply this: white knights need redemption, too.

Back when I first started Difficult Run and ran it solo for a while in 2012, I wrote on the “About” page that “I am the prodigal son’s older brother.” He’s the one I identify with the most in that story. Superficially he’s the good guy because he he didn’t run off and blow his inheritance on booze and hookers and end up starving and eating with the pigs, but if you look deeper he’s the same as his younger brother. The prodigal son’s primary failing was a lack of love and loyalty for his family. He wanted the money (his inheritance) more than he wanted his home, and everything else follows from that. Sure, the elder brother stayed home, but when he sees the party everyone is throwing for the young son, he starts whining and complaining. Those complaints show is that he is also pretty contemptuous of his home and his father’s love.

That’s why the father’s response to his older son is so incredibly tragic: “And he said unto him, Son, thou art ever with me, and all that I have is thine.”[ref]Luke 15:31[/ref]

In other words, he’s saying that if you really cared about me, then you would think that the last several years you spent living with me in comfort and peace while your brother was hitting rock bottom were the reward. Did the elder brother stay home because he was loyal, or because he was afraid? Did he love his dad, or did he think he was doing him a favor? Was he interested in doing the right thing for its own sake, or because he thought he’ be rewarded? In the end, the fact that he’s jealous of his younger brother shows that he is essentially the same as his younger brother. Just a little more risk-averse. Like me.

We all need heroes we can relate to. For me, that means white knights. Not because they are better, not because they think they are better, and not because maybe other people think they are better. But because they aren’t.

The Spirituality of U2

Obviously I know the band u2. Everyone knows the band U2, and I like the songs of their’s that I’ve heard. And I now all about Bono’s humanitarian efforts. But I’ve never really gotten into u@ in a big way, so I’ve never really paid attention to the lyrics, so I never really knew that Bono’s Christian faith is important to him; important enough to show up in his lyrics on a regular basis. Thankfully, a long article from Deseret News headlined The biggest band in the world is also one of the most spiritual has cleared that up for me.

The article goes through too many examples of religious themes in the music across many of the bands albums for me to list here, and easily enough to convince me that–like songwriting from Brandon Flowers of The Killers–the religious themes are deeply intertwined with their music. Looks like I’ve got a lot of listening to do.

Can Christians Rock?

There’s an interesting review over at First Things of Christopher Partridge’s new book, The Lyre of Orpheus. Partridge’s theory, according to First Things’ Stephen Webb is as follows:

Rock is essentially transgressive. Christianity upholds a sacred order that excludes the profane. Therefore, contemporary Christian music cannot be true rock and roll, because it is “unable to establish a credible presence in [rock’s] profane affective space.”

Webb contests this theory, but he does so very weakly, writing: “Satan might or might not be beyond redemption, but everything else, including the devil’s music, isn’t.” That may be true, but it’s not really informative (how does one go about redeeming a genre or music?) nor does it actually address the core point. If rock is intrinsically transgressive, then when you redeem it you don’t really have rock anymore. The question that Partridge begs, and that Webb never spots, is this: transgressive of what?

I know it’s only a short review, but all the musicians noted were born in the 1950s – 1970s. It’s certainly easy to surmise that in the time they were making music (the 1970s and 1980s) traditional family values were still relatively dominant in America. In that context it makes sense to assume that “transgressive” meant contradicting these traditional values of modesty, self-restraint, and fidelity. But that assumption doesn’t make sense any more. No big surprise, by the way, Partridge himself was born in 1961. His cultural reference points were already stale in the last millennium.

By coincidence, I also picked up this story from the Daily Beast today: Watch What You Say, The New Liberal Power Elite Won’t Tolerate Dissent. The article’s first paragraph shows what Partridge and especially Web could have been talking about all along:

In ways not seen since at least the McCarthy era, Americans are finding themselves increasingly constrained by a rising class—what I call the progressive Clerisy—that accepts no dissent from its basic tenets. Like the First Estate in pre-revolutionary France, the Clerisy increasingly exercises its power to constrain dissenting views, whether on politics, social attitudes or science.

When the powers that are in charge change, so does the meaning of the term “transgressive.” Music that is truly subversive now is effectively opposite of what was subversive back then. This makes sense: terms like “subversive” and “transgressive” are value-neutral without context. They are good or bad and useful or damaging entirely dependent on what it is they are attacking and promoting in its stead. It’s entirely possible for Christian rock to be subversive of the dominant culture while authentically embracing Christian tenets. In fact, because it faithfully embraces Christian tenets. You probably won’t get this if by “Christian rock” you are thinking of the kind of praise or worship music that you’ll find on Christian radio stations, because that music is geared towards being played in houses of worship. It doesn’t oppose or subvert anything. It probably can’t be real rock and roll. But it’s only one particular variant of Christian rock. How about my favorite band of all time: Thrice?

Yeah, I’m biased, but pay attention to which way the causality runs. I’m not endorsing Thrice as an example of a counter-cultural Christianity because I like the band. I liked the band in the first place precisely because of its subversive (in relationship to the Clerisy) nature. Nowhere is this more obvious than the official video of their song “Image of the Invisible” (off of their 2005 album Vheissu). The music alone screams beleaguered defiance and the lyrics match it perfectly: So raise the banner, bend back your bows / Remove the cancer, take back your souls and Though all the world may hate us, we are named / The shadow overtake us, we are known. But, in case the subversion theme wasn’t overt enough, the video drills the point home with a distinctly dystopian theme in which Christians are part of a modern underground resistance movement, fighting to get out a message that the world hates, has always hated, and will always hate.

Has Webb forgotten the relationship between the Church and the world depicted so directly in the New Testament, culminating in the crucifixion of God’s Son by the greatest political empire of the time? How about Paul’s words to the Ephesians:

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.

Give me a break, Christ’s alleged crimes were basically variants of “subversion.” Subversion of the orthodox religious view and subversion of the Roman political order. We worship someone who was tried and executed for subversion 2,000 years ago, and Partridge thinks some aging rock stars have a damn thing to teach Christians about what it means to be subversive?

I think not.