This is part of the DR Book Collection.

Let me start out by saying upfront: this book rocked my world a little bit. As any readers of Difficult Run will probably know by now, I’m extremely critical of contemporary social justice activism. I try not to use the pejorative term “social justice warrior” these days, but you’ll recognize the notion by buzzwords like “trigger warning” or “microaggression.” And so when I picked up Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, it was with a side of skepticism.

Let me start out by saying upfront: this book rocked my world a little bit. As any readers of Difficult Run will probably know by now, I’m extremely critical of contemporary social justice activism. I try not to use the pejorative term “social justice warrior” these days, but you’ll recognize the notion by buzzwords like “trigger warning” or “microaggression.” And so when I picked up Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, it was with a side of skepticism.

On the other hand, being a Christian means taking issues of social justice seriously. Of course, what I have in mind when I say “social justice” might not line up very well with the social justice movement as it exists today, but there’s no escaping the simple reality that both Old Testament prophets and the New Testament teachings of Christ are often most pointed on precisely the topic of justice in society.

“The Lord standeth up to plead,” wrote Isaiah, “and standeth to judge the people.” And what was God’s condemnation? “What mean ye that ye beat my people to pieces, and grind the faces of the poor?”[ref]Isaiah 3:13, 15[/ref] And in one of Jesus’s most powerful parables, he taught that visiting prisoners was a service to God, saying, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” And then, lest there be any confusion, he also stated that, “Inasmuch as ye did it not to one of the least of these, ye did it not to me.”[ref]Matthew 25:40,45[/ref]

So, a book about oppressing vulnerable people by imprisonment? My skepticism was on hand, but my mind was also open. This is important stuff, and I wanted to hear what Alexander had to say.

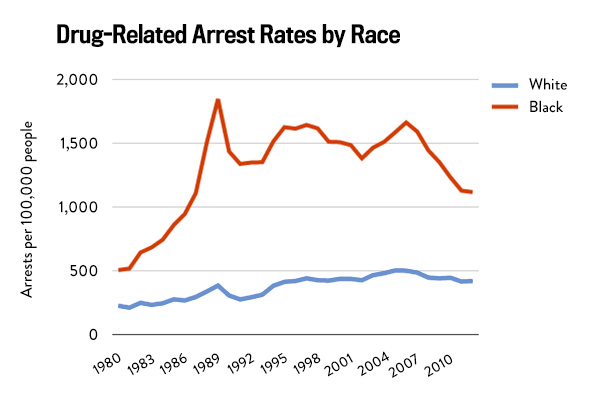

I’ll get right down to it: on her primary argument, she has me convinced. And this is her primary argument: although the War on Drugs is ostensibly race-neutral, it systematically impacts black and poor Americans to the detriment of their communities while scrupulously avoiding the same kinds of impacts on white and prosperous Americans.

The first component of that argument, that the War on Drugs has a racially disparate impact, is based on a central fact: whites and blacks commit drug crimes at roughly comparable rates, but blacks are far more likely to be charged and convicted of crimes. Here is how that plays out in practice. First, Alexander notes that:

It is impossible for law enforcement to identify and arrest every drug criminal. Strategic choices must be made about whom to target and what tactics to employ. Police and prosecutors did not declare the War on Drugs, and some initially opposed it, but once the financial incentives for waging the war became too attractive to ignore, law enforcement agencies had to ask themselves, if we’re going to wage this war, where should it be fought and who should be taken prisoner?

The answer is simple: vulnerable communities will be targeted (because they can’t fight back politically) and specifically racial minorities will be targeted (because of stereotypes about drug offenders). In regards to the first, she writes:

Confined to ghetto areas and lacking political power, the black poor are convenient targets.

And in regards to the second, she writes:

In 2002 a team of researchers at the University of Washington decided to take the defense of the drug war seriously by subjecting the arguments to empirical testing in a major study of drug law enforcement in a racially mixed city, Seattle. The study found that, contrary to the prevailing common sense, the high arrest rates of African American in drug law enforcement could not be explained by rates of offending. Nor could they be explained by other standard excuses, such as the ease and efficiency of policing open-air drug markets, citizen complaints, crime rates, or drug-related violence. The study also debunked the assumption that white drug dealers deal indoors, making their criminal activity more difficult to detect. The authors found that it was untrue stereotypes about crack markets, crack dealers, and crack babies–not facts–that were driving discretionary decision-making by the Seattle police department.[ref]Some specific stats from the study are available here.[/ref]

Alexander’s case is particularly strong when she notes the difference between mandatory sentences for stereotypically white and black versions of the same drug (e.g. cocaine vs. crack) and provides the legal history of attempts to challenge the racially disparate outcomes of the criminal justice system. There’s McCleskey v. Kemp, for example, in which a death penalty conviction was challenged on the basis of research by David C. Baldus showing that “even after taking account of 39 nonracial variables, defendants charged with killing white victims were 4.3 times as likely to receive a death sentence than defendants charged with killing blacks.”[ref]Wikipedia[/ref] The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, however. Alexander writes:

The majority observed that significant racial disparities have been found in other criminal settings beyond the death penalty, and the McCleskey’s case implicitly calls into question the integrity of the entire system. In the Court’s words, “taken to its logical conclusion, Warren McCleskey’s claim throws into serious question the principles that underly our criminal justice system. If we accepted McCleskey’s claim that racial bias has impermissibly tainted the capital sentencing decision, we could soon be faced with similar claims as to other types of penalty.” The Court openly worried that other actors in the criminal justice system might also face scrutiny for allegedly biased decision-making if similar claims about bias in the system were allowed to proceed. Driven by these concerns, the Court rejected McCleskey’s claim that Georgia’ death penalty system violates the 8th Amendments ban on arbitrary punishment, framing the critical question as whether the Baldus Study demonstrated a Constitutionally unacceptable risk of discrimination. It’s answer was no. The Court deemed the risk of racial bias in Georgia’s capital sentencing scheme Constitutionally acceptable. Justice Brennan pointedly noted in his dissent that the Court’s opinion “seems to suggest a fear of too much justice.”

According to an LA Times survey of legal scholars, it’s one of the worst post-World War II SCOTUS decisions.[ref]Wikipedia[/ref] Prior to reading this book, I’d never heard of it. Nor had I heard of United States v. Armstrong,[ref]There’s no Wikipedia article for that one, but here’s the decision and an LA Times article from the year it was decided.[/ref] which found that defendants who suspected that they were victims of discrimination had to prove that they were victims of that discrimination first, before they could get access to prosecutorial records that would be necessary to prove the question of discrimination. Alexander writes:

Unless evidence of conscious, intentional bias on the part of the prosecutor could be produced, the court would not allow any inquiry into the reasons for or causes of apparent racial disparities in prosecutorial decision making.

Her case is also very strong when she makes two key points. First, violent crime can’t explain mass incarceration. This is something that came up in the Facebook comments after I posted Mass Incarceration is Not a Myth. Walker Wright recently wrote a solid follow-up piece with even more data: The Stock and Flow of Drug Offenders. So one of the common rebuttals to Alexander’s criticism–that incarceration is about violent crime rather than drugs–doesn’t hold up. However, it is worth noting that black men do commit violent crimes at higher rates than white men (in contrast to drug offenses) and so higher differential rates of incarceration in that case are not evidence of racial discrimination, a point that Alexander concedes.[ref]Although she also argues that, once you account for poverty, this gap narrows considerably.[/ref]

Second, and even more strongly, she points out that incarceration itself is not the real problem. The problem is that a felony conviction is basically the modern equivalent of a scarlet-F: it makes you basically unemployable, excludes you from many government programs (like student loans), and therefore makes it all but impossible for people who have paid their debt to society (as the saying goes) to actually re-enter that society. This is why Alexander refers to “a system of control” that extends well beyond literal prisons. She’s right.

But there are some parts where I think Alexander gets important things very wrong. First, she tends to be a little blind to issues of class, which is also a leading problem with most contemporary social justice activists. Interestingly enough, Cornell West–in the introduction–draws this point out much more clearly than Alexander does in her own book, writing:

There is no doubt that if young white people were incarcerated at the same rates as young black people, the issue would be a national emergency. But it is also true that if young black middle and upper class people were incarcerated at the same rates as young black poor people, black leaders would focus much more on the prison-industrial complex. Again, Michelle Alexander has exposed the class bias of much of black leadership as well as the racial bias of American leadership for whom the poor and vulnerable of all colors are a low priority.

After reading the entire book, it sounds to me like West went much farther than Alexander was willing to do, although she has a lot of the pieces right there in the book. Alexander is very critical of affirmative action, first arguing that it does more harm than good and then arguing that middle- and upper-class blacks have in effect accepted affirmative action as a kind of “racial bribe” for their complicity in mass incarceration:

It may not be easy for the civil rights community to have a candid conversation about [affirmative action]. Civil rights organizations are populated with beneficiaries of affirmative action (like myself) and their friends and allies. Ending affirmative action arouses fears of annihilation. The reality that so many of us would disappear overnight from colleges and universities nationwide if affirmative action were banned, and that our children and grandchildren might not follow in our footsteps, creates a kind of panic that is difficult to describe.

As a result of both affirmative action and the takeover of civil rights organizations by lawyers, she concludes that the entire movement is mired in hypocrisy and inaction:

Try telling a sixteen-year-old black youth in Louisiana who is facing a decade in adult prison and a lifetime of social, political, and economic exclusion that your civil rights organization is not doing much to end the War on Drugs–but would he like to hear about all the great things that are being done to save affirmative action? There is a fundamental disconnect today between the world of civil rights advocacy and the reality facing those trapped in the new racial undercaste.

In examples like these, Alexander is clearly demonstrating that race alone cannot explain what is happening, but she is still unwilling to follow that logic to its conclusion. We’ll return to that in a moment, because it’s my biggest problem with her analysis. Before we get there, however, I want to point out that she also tackles a lot of the conservative criticisms head on. In addition to the violence/drug question, there is the issue of “gangsta culture.” Isn’t it a fact, conservatives might ask, that inner city black culture glorifies illegal and anti-social conduct, and that therefore there’s something rotten at the heart of black culture?

This is an important question, because it is a serious one but also one that conservatives generally can’t ask without simply being shouted down as racist. The inability to have a serious conversation about black culture as it relates to crime is probably the single biggest cause of our dysfunctional national conversation about race (or the lack thereof). As long as social conservatives aren’t even allowed to voice their most important questions, there’s really nothing to talk about. But Alexander doesn’t dismiss the question; she takes it seriously and addresses it. She does so in two ways. First:

Remarkably, it is not uncommon today to hear media pundits, politicians, social critics, and celebrities–most notably Bill Cosby–complain that the biggest problem black men have today is that they “have no shame.” Many worry that prison time has become a badge of honor in some communities–“a rite of passage” is the term most commonly used in the press. Other claims that inner-city residents no longer share the same value system as mainstream society, and therefore are not stigmatized by criminality. Yet as Donald Braman, author of Doing Time on the Outside states: “One can only assume that most participants in these discussions have had little direct contact with the families and communities they are discussing.”

Over a four-year period, Braman conducted a major ethnographic study of families affect by mass incarceration in Washington, D.C., a city where three out of every four young black men can expect to spend some time behind bars. He found that, contrary to popular belief, the young men labeled criminals and their families are profoundly hurt and stigmatized by their status: “They are not shameless; they feel the stigma that accompanies not only incarceration but all the other stereotypes that accompany it–fatherlessness, poverty, and often, despite very intent to make it otherwise, diminished love.” The results of Braman’s study have been largely corroborated by similar studies elsewhere in the United States.

If this is correct–and I have no reason to doubt it–then it means that the idea of a monolithic culture of disrespect for law and glorification of crime (not to mention outright misogyny) is a myth. Even in the inner-city there is respect for rule of law, manifested in deep shame accompanying incarceration.

But if that’s true, why is black culture most frequently represented by gangsta rap that does, in fact, engage in that kind of anti-sociality? That’s Alexander’s second point:

The worst of gangsta rap and other forms of blaxploitation (such as VH1’s Flavor of Love) is best understood as a modern-day minstrel show, only this time televisd around the clock for a worldwide audience. It is a for-profit display of the worst racial stereotypes and images associated wit the era of mass incarceration–an era in which black people are criminalized and portrayed as out-of-control, shameless, violent, over-sexed, and generally undeserving.

Like the minstrel shows of the slavery and Jim Crow eras, today’s displays are generally designed for white audiences. The majority of the consumers of gangsta rap are white, suburban teenagers. VH1 had its best ratings ever for the first season of Flavor of Love–ratings drive by large white audiences. MTV has expanded its offerings of black-themed reality shows in the hopes of attracing the same crowd. The profits to be made from racial stigma are considerable, and the fact that blacks–as well as whites–treat racial oppression as a commodity for consumption is not surprising. It is a familiar form of black complicity with racialized systems of control.

The most important part of this response, again, is simply the willingness to engage the issue seriously. This is critical, because once this issue is on the table it’s possible for dialogue. Additionally, however, I find her two-pronged approach compelling.

OK, so let’s get back to my biggest complaint with Alexander’s work: what’s behind the racially disparate impact of the War on Drugs? Throughout the book, she contends that (1) it is exclusively racist and (2) it is deliberately racist. Neither of these claims are supported by her own arguments, and they hurt her case. This starts fairly early on, and then runs consistently throughout the book. Here’s an early example:

The language of the Constitution itself was deliberately colorblind. The words “slave” or “negro” were never used, but the document was built upon a compromise regarding the prevailing racial caste system. Federalism, the division of power between the states and the federal government was the device employed to protect the institution of slavery and the political power of slave-holding states.

In other words, Alexander is arguing that federalism is nothing but a ruse to covertly encode racism within the Constitution. It’s true that federalism enabled slavery to continue by making it a state-level issue, but to say that that is why federalism existed is to deny that the Founders had any independent, reasonable reasons to support federalism, and that’s not plausible. Federalism was, first and foremost, an attempt to avoid the centralized tyranny of the British monarchy that was the ideological raison d’etre of the American Revolution. To dismiss that as incidental is to fundamentally misunderstand the history and philosophy of the Constitution.

At another point, she clearly states that “all racial caste systems, not just mass incarceration, have been supported by racial indifference,” but she also argues that–at the dawn of the era of mass incarceration–“Conservative whites began once again to search for a new racial order that would conform to the needs and constraints of the time.” In other words, Federalism was part of an intentionally racist program (slavery), separate-but-equal was part of an intentionally racist program (Jim Crow), and color-blindness is part of an intentionally racist program (mass incarceration). But I’m not convinced.

Oh, there’s strong evidence–smoking gun evidence, as far as I’m concerned–that Nixon and Reagan appealed to racism as part of their “law and order” approach to the War on Drugs. But that was nearly a half-century ago. And no, I don’t think that the US has emerged into a post-racial utopia since then. Obviously not! But I do think Walter Williams had it right:

Back in the late 1960s, during graduate study at UCLA, I had a casual conversation with Professor Armen Alchian, one of my tenacious mentors. . . . I was trying to impress Professor Alchian with my knowledge of type I and type II statistical errors.

I told him that my wife assumes that everybody is her friend until they prove differently. While such an assumption maximizes the number of friends that she will have, it also maximizes her chances of being betrayed. Unlike my wife, my assumption is everyone is my enemy until they prove they’re a friend. That assumption minimizes my number of friends but minimizes the chances of betrayal.

Professor Alchian, donning a mischievous smile, asked, “Williams, have you considered a third alternative, namely, that people don’t give a damn about you one way or another?” . . . During the earlier years of my professional career, I gave Professor Alchian’s question considerable thought and concluded that he was right. The most reliable assumption, in terms of the conduct of one’s life, is to assume that generally people don’t care about you one way or another. It’s a mistake to assume everyone is a friend or everyone is an enemy, or people are out to help you, or people are out to hurt you.

Williams (who is a black economist) was actually talking specifically about race relations in his piece. He said:

Are white people obsessed with and engaged in a conspiracy against black people? I’m guessing no, and here’s an experiment. Walk up to the average white person and ask: How many minutes today have you been thinking about a black person? If the person wasn’t a Klansman or a gushing do-gooder, his answer would probably be zero minutes. If you asked him whether he’s a part of a conspiracy to undermine the welfare of black people, he’d probably look at you as if you were crazy. By the same token, if you asked me: “Williams, how many minutes today have you been thinking about white people?” I’d probably say, “You’d have to break the time interval down into smaller units, like nanoseconds, for me to give an accurate answer.” Because people don’t care about you one way or another doesn’t mean they wish you good will, ill will or no will.

Alexander had it right when she talked about “racial indifference.” Even overt racism is virtually never racism for racism’s sake. Alexander herself said, “By and large, plantation owners were indifferent to the suffering caused by slavery; they were motivated by greed.”

So, based on the evidence she presents, what’s the real story of racism in America? Powerful people want to maintain their power at the expense of less powerful people. Race, which Alexanders correctly observes “is a relatively recent development,” is only the most potent and insidious means of perpetuating inequalities that are, at their roots, totally agnostic with respect to race or creed or language or ethnicity or religion. All of these are just social markers that can ennable power inequality, but which are mostly irrelevant in and of themselves. So even when race is appealed to directly, it’s always a means to another end, never an end in itself.

So much for the idea of deliberate racism.[ref]I haven’t dismissed it entirely, but recontextualized it as a means to an end.[/ref] What about the exclusivity of the racial aspects of mass incarceration? Here, Alexander uses a military analogy:

Of course, the fact that white people are harmed by the drug war does not mean they are the real targets, the designated enemy. The harm white people suffer in the drug war is much like the harm Iraqi civilians suffer in U.S. military actions targeting presumed terrorists or insurgents. In any way, a tremendous amount of collateral damage is inevitable. Black and brown people are the principal targets in this war; white people are collateral damage.

No analogy is perfect, of course, but in this case her chosen analogy undercuts rather than strengthens her position. The point of “collateral damage” is not merely that it is incidental, but that it is scrupulously avoided whenever possible. I’m not saying that the US is perfect at that, but avoiding collateral damage–at least in theory–is what we strive for.

But if white people were really “collateral damage” in the War on Drugs, then of course we would not only see fewer of them in jail, we’d see none at all. Unlike dropping bombs from miles up, it’s easy to ascertain the race of a suspect before they go to jail. If race were the exclusive characteristic–if mass incarceration were designed specifically to target exclusively African Americans–then why are white drug dealers ever sent to jail? Or Asian, or Hispanic, Native American, etc? Alexander might argue, “to provide enough cover for people to believe it’s truly race-neutral,” but that explanation is thin and overly complex. It falls for the same fundamental mistake as all conspiracy theories: a drastic overestimation in the human ability to plan the future. The War on Drugs was not a consciously designed system of racial oppression that ensnares a set number of white people just to provide a thin veneer of racial neutrality. To see that this is true, just ask yourself: “Who determines the requisite number of white people required to give the system cover, and how do they coordinate all the local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies to make sure the quota is hit?” The whole setup doesn’t makes sense.

No, the War on Drugs isn’t a cleverly designed mechanism. It is an opportunistically cobbled-together mish-mash of policies, laws, practices, and agencies that exploits the vulnerable and powerless because of the blind logic of power, not because it was designed to target minorities. The War on Drugs also feeds off of and reinforces racist stereotypes. It is, without doubt in my mind, systematically racist. But it’s not exclusively racist; it’s also classist. And it does not exist today because of deliberate racism; but because of inertia, racial indifference, and power politics.

There are not just technicalities. They have profound implications for how we talk about race, how we analyze racist institutions, and what solutions we deploy against them. And this is where I found Alexander’s logic to be at its weakest. She is steadfastly set against colorblind policies. And, given the ability of the criminal justice system to be ostensibly colorblind and still produce racist outcomes, I understand. But her logic breaks down when she dismisses colorblindness entirely. This is most obvious when she writes that:

The uncomfortable truth, however, is that racial differences will always exist among us. Even if the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, and mass incarceration were completely overcome, we would remain a nation of immigrants (and indigenous people) in a larger world divided by race and ethnicity. It is a world in which there is extraordinary racial and ethnic inequality, and our nation has porous boundaries. For the foreseeable future, racial and ethnic inequality will be a feature of American life.

Contrast that with her prior statement that “The concept of race is a relatively recent development. Only in the past few centuries, owing largely to European imperialism, have the world’s people been classified along racial lines.” If race is a “recent development,” can we really be so confident that “racial differences will always exist among us?”

No, we can’t. Race is a fluid concept. Not only was it largely invented in the 17th century, but it continued to change dramatically after that. In the 19th and 20th century, Catholic Irish, Jews, and many other groups were considered non-white. Today, the Irish have a distinct cultural identity within the United States, but nobody would seriously argue that they are non-white. How do the Irish fare vs. narrower racial definitions of whiteness on metrics like housing, household wealth, income, or educational attainment? My guess? Nobody knows because nobody even measures it.[ref]I did a few quick Google searches and found nothing, but if you’ve got something, let me know.[/ref]

I will agree with Alexander this far: race-blindness didn’t stop the racist bent of mass incarceration and it never can. We may need to be proactive about measuring racial outcomes, at a minimum, in our efforts to overhaul the criminal justice system. However, I’m not convinced that the dream of a colorblind society should be so easily dismissed.

Of course, the historical model of an ever-expanding category of whiteness won’t work in the future. First, because any racial definition has to have at least two groups. So if “white” exists as a category, there will have to be non-white. As long as we see the world in racial terms, universal racial inclusiveness is impossible. Second, I would hardly expect African Americans to be enthusiastic about a solution of universal whiteness even if it were possible (which it’s not).

“It’s OK, you can be considered white, too, one day,” is not an acceptable solution to our history of racial prejudice.

There are alternative possibilities, however. The way out of racial binaries is to drop race as a valid characteristic. A Marxist can do this by seeing only the bourgeois and the proletariat, just as one proof-of-concept. But, if we don’t want to all become Marxist, then we’ll have to figure something else out. Nationalism is another approach, although not without its own complications. And who knows: there may be other concepts we haven’t even thought of yet. The point is, I don’t think it’s a bad thing to hope for a day when the difference between an African American and an Irish American becomes much more like the difference between an American whose family came from Scandinavia and one whose family came from Italy.

We can’t get there from here if we do not redress the real and obvious racial disparities within our nation, and the racist War on Drugs seems like a great place to start. But I’m also not sure if we can get there from here as long as we view colorblindness as an intrinsically undesirable destination. If we insist on defining people in racial terms, then Alexander is probably right: “racial and ethnic inequality will be a feature of American life.” So maybe we shouldn’t plan on doing that forever.

At the end of the day, I found this book to have its flaws, but on the central points it has me convinced. I was already skeptical of the War on Drugs, but now I’m downright convinced that it is a needlessly oppressive and exploitative racist and classist juggernaut that somehow we need to stop.

The outcome of the election still has many rocking. I had taken up reading GMU law professor Ilya Somin’s

The outcome of the election still has many rocking. I had taken up reading GMU law professor Ilya Somin’s  I’ve been a fan of New Testament scholar N.T. Wright’s work for the last several years. His Surprised by Hope even earned a much-coveted spot among my Honorable Mentions on my

I’ve been a fan of New Testament scholar N.T. Wright’s work for the last several years. His Surprised by Hope even earned a much-coveted spot among my Honorable Mentions on my  If readers couldn’t tell,

If readers couldn’t tell,  Philosopher Joseph M. Spencer has already made some

Philosopher Joseph M. Spencer has already made some  The late Peter Drucker (1909-2005) is one of the most influential management thinkers of all time as well as “the most cited management writer in the textbooks, exceeding that of Abraham Maslow, Max Weber, and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth…”[ref]Patricia G. McLaren, Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos, “Disseminating Drucker: Knowledge, Tropes and the North American Management Textbook,” Journal of Management History 15:4 (2009): 391.[/ref] His influence has been felt worldwide,

The late Peter Drucker (1909-2005) is one of the most influential management thinkers of all time as well as “the most cited management writer in the textbooks, exceeding that of Abraham Maslow, Max Weber, and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth…”[ref]Patricia G. McLaren, Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos, “Disseminating Drucker: Knowledge, Tropes and the North American Management Textbook,” Journal of Management History 15:4 (2009): 391.[/ref] His influence has been felt worldwide,