The World Bank’s latest Doing Business report has been released. The report “measures regulations affecting 11 areas of the life of a business. Ten of these areas are included in this year’s ranking on the ease of doing business: starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting minority investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts and resolving insolvency. Doing Business also measures labor market regulation, which is not included in this year’s ranking.”

Its key findings are as follows:

- Doing Business 2017: Equal Opportunity for All finds that entrepreneurs in 137 economies saw improvements in their local regulatory framework last year. Between June 2015 and June 2016, the report, which measures 190 economies worldwide, documented 283 business reforms. Reforms reducing the complexity and cost of regulatory processes in the area of starting a business were the most common in 2015/16, as in the previous year. The next most common reforms were in the areas of paying taxes, getting credit and trading across borders. Read about business reforms.

- Brunei Darussalam, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Belarus, Indonesia, Serbia, Georgia, Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain were the most improved economies in 2015/16 in areas tracked by Doing Business. Together, these 10 top improvers implemented 48 regulatory reforms making it easier to do business.

- Economies in all regions are implementing reforms easing the process of doing business, but Europe and Central Asia continues to be the region with the highest share of economies implementing at least one reform—96% of economies in the region have implemented at least one business regulatory reform.

- Doing Business includes a gender dimension in four of the 11 topics sets. Starting a business, registering property and enforcing contracts present a gender dimension for the first time this year. Labor market regulation already captured gender disaggregated data in last year’s report.

- This year’s report expands the paying taxes topic set to cover postfiling processes—what happens after a firm pays taxes—such as tax refunds, tax audits and administrative tax appeals.

- This year’s report also includes an annex with analysis on a pilot indicator on public procurement regulations.

- The report features six case studies in the areas of getting electricity, getting credit: legal rights, getting credit: credit information, protecting minority investors, paying taxes and trading across borders as well as two annexes in the areas of labor market regulation and selling to the government. The case studies and annexes either present new indicators or provide further insights from the data collected through methodology changes implemented in the past two years. See all case studies.

A number of things jumped out at me. First off, the rankings of the oft-praised Nordic countries, particularly Denmark and Sweden. See how those two countries compare to the U.S. below.

| World Bank Rankings | Denmark | Sweden | U.S. |

| Overall | 3 | 9 | 8 |

| Starting a business | 24 | 15 | 51 |

| Construction permits | 6 | 25 | 39 |

| Getting electricity | 14 | 6 | 36 |

| Registering property | 12 | 10 | 36 |

| Getting credit | 32 | 75 | 2 |

| Protecting minority investors | 19 | 19 | 41 |

| Paying taxes | 7 | 28 | 36 |

| Trading across borders | 1 | 18 | 35 |

| Enforcing contracts | 24 | 22 | 20 |

| Resolving insolvency | 8 | 19 | 5 |

Denmark ranks higher than the United States with Sweden only a spot behind.[ref]Full rankings found on pgs. 203 (Denmark), 242 (Sweden), and 248 (United States) of the full report.[/ref] Yet, in both Denmark and Sweden it is easier to

- Start a business

- Get a construction permit

- Get electricity

- Register property

- Protect minority investors

- Pay taxes

- Trade across borders

As Will Wilkinson put it, “[Y]ou cannot finance a Danish-style welfare state without free markets and large tax increases on the middle class. If you want Danish levels of social spending, you need Danish middle-class tax rates and a relatively unfettered capitalist economy.”

However, the next few graphs are probably some of the most interesting bits of the report:

As the report explains,

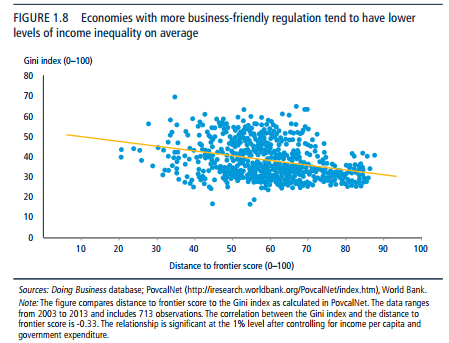

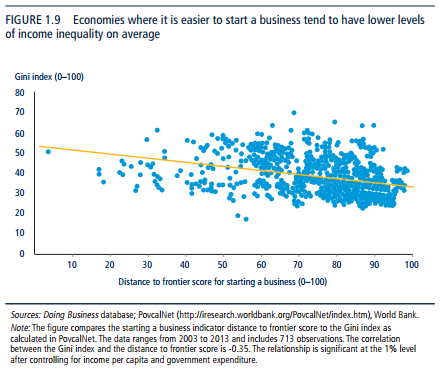

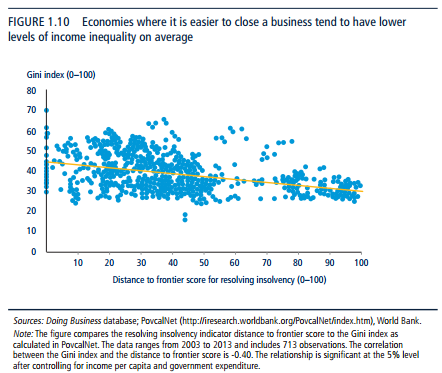

research shows that where business regulation is simpler and more accessible, firms start smaller and firm size can be a proxy for the income of the entrepreneur. Doing Business data confirms this notion. There is a negative association between the Gini index, which measures income inequality within an economy, and the distance to frontier score, which measures the quality and efficiency of business regulation when the data are compared over time (figure 1.8).

Data across multiple years and economies show that as economies improve business regulation, income inequality tends to decrease in parallel. Although these results are associations and do not imply causality, it is important to see such relation. The results differ by regulatory area. Facilitating entry and exit in and out of the market—as measured by the starting a business and resolving insolvency indicators—have the strongest link with income inequality reduction (figures 1.9 and 1.10). These two Doing Business indicators are focused on equalizing opportunities and access to markets (pgs. 11-12).

In short, lower income inequality is correlated with simpler, business-friendly regulations. Anyone worried about income inequality should take note.

I recommend taking a look at the data for yourself. Lots of good stuff.

In Scotland, students exercised complete consumer control over with whom they studied and which subjects they deemed relevant. Oxford—and in fact most other European universities—employed a system similar to the way that American universities handle tuition payments today: One tuition payment was made directly to the university, and the university decided how to distribute what came in…Smith points out how [Oxford] often fell short of the Scottish system, where direct payment of fees served as motivation for faculty responsibility. “The endowments of [British] schools and colleges have necessarily diminished more or less the necessity of application in the teachers,” Smith writes in his opening sally against bundling the costs of education. “In the university of Oxford, the greater part of the publick professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching.” In the the Scottish system, “the salary makes but a part, and frequently but a small part of the emoluments of the teacher, of which the greater part arises from the honoraries or fees of his pupils,” he explains.

In Scotland, students exercised complete consumer control over with whom they studied and which subjects they deemed relevant. Oxford—and in fact most other European universities—employed a system similar to the way that American universities handle tuition payments today: One tuition payment was made directly to the university, and the university decided how to distribute what came in…Smith points out how [Oxford] often fell short of the Scottish system, where direct payment of fees served as motivation for faculty responsibility. “The endowments of [British] schools and colleges have necessarily diminished more or less the necessity of application in the teachers,” Smith writes in his opening sally against bundling the costs of education. “In the university of Oxford, the greater part of the publick professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching.” In the the Scottish system, “the salary makes but a part, and frequently but a small part of the emoluments of the teacher, of which the greater part arises from the honoraries or fees of his pupils,” he explains.

One of the more encouraging findings [of one study] was that, even in the face of some of life’s most tragic events like the death of a spouse, after a few years, people do recover to the same level of wellbeing they had before their spouse passed away. But this was not the case for those who were unemployed for a prolonged period of time — particularly not for men. Our wellbeing actually recovers more rapidly from the death of a spouse than it does from a sustained period of unemployment. This doesn’t mean that getting fired will harm your wellbeing forever. The same study also found that being laid off from a job in the last year did not result in any significant long-term changes. The key is to avoid sustained periods of unemployment (more than a year) when you are actively looking for a job but unable to find one. In addition to the obvious loss of income from prolonged unemployment, the lack of regular social contact and the daily boredom might be even more detrimental to your wellbeing.

One of the more encouraging findings [of one study] was that, even in the face of some of life’s most tragic events like the death of a spouse, after a few years, people do recover to the same level of wellbeing they had before their spouse passed away. But this was not the case for those who were unemployed for a prolonged period of time — particularly not for men. Our wellbeing actually recovers more rapidly from the death of a spouse than it does from a sustained period of unemployment. This doesn’t mean that getting fired will harm your wellbeing forever. The same study also found that being laid off from a job in the last year did not result in any significant long-term changes. The key is to avoid sustained periods of unemployment (more than a year) when you are actively looking for a job but unable to find one. In addition to the obvious loss of income from prolonged unemployment, the lack of regular social contact and the daily boredom might be even more detrimental to your wellbeing.