Class disruptions are known to worsen educational achievement in the short run, but new research demonstrates that being exposed to disruptive peers can even lead to worse adult outcomes:

Results indicate that there are persistent effects on both test scores and educational attainment. We estimate that exposure to one disruptive peer in a class of 25 throughout elementary school is associated with a 0.02 standard deviation reduction in test scores during high school, and nearly a one percentage point reduction in the likelihood of receiving a college degree. This suggests that the impact of disruptive peers does persist with respect to educational outcomes years afterward.

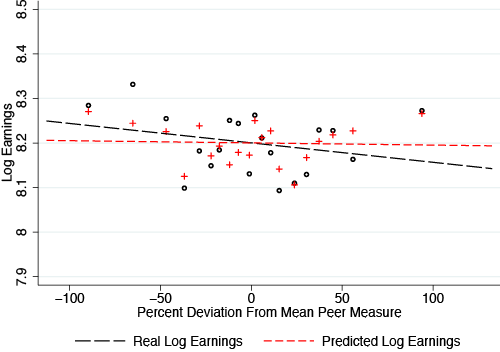

…Figure 1 shows that while individuals who have idiosyncratically low exposure to disruptive peers (those on the left-hand side) tend to earn more than predicted, those with idiosyncratically high exposure tend to earn somewhat less than predicted. Specifically, we estimate that exposure to one disruptive peer in a class of 25 throughout elementary school reduces earnings by 3–4%, with effects being driven by exposure to disruptive boys.

The researchers conclude,

Our findings…speak to the extent to which differential exposure to disruptive students can lead to income inequality later in life. We calculate that the increased exposure to disruptive peers by students from low-income families can explain 5–6% of the earnings gap between adults who grew up in low versus high-income households. This is significant given that we have only one particular measure of disruptive peers in our sample, and it highlights the extent to which sorting into schools can lead to the persistence of long-term income inequality across households.

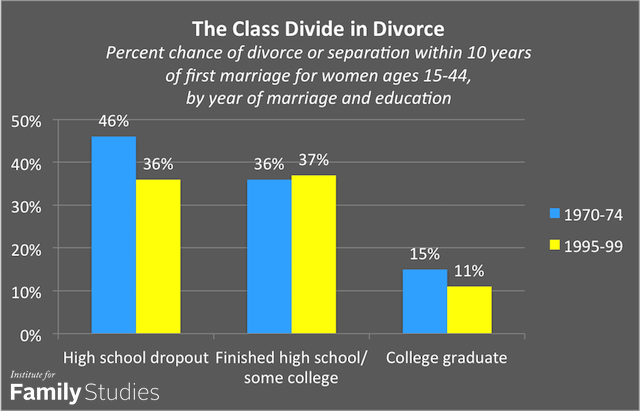

While the researchers look specifically at children in families exposed to domestic violence, their findings have broader implications about family breakdown, behavioral problems, and income inequality. As Princeton sociologist Sara McLanahan and Harvard’s Christopher Jencks explain, family breakdown can lead to more behavioral problems in children:

[A] father’s absence increases antisocial behavior, such as aggression, rule breaking, delinquency, and illegal drug use. These antisocial behaviors affect high school completion independent of a child’s verbal and math scores. Thus it appears that a father’s absence lowers children’s educational attainment not by altering their scores on cognitive tests but by disrupting their social and emotional adjustment and reducing their ability or willingness to exercise self-control. The effects of growing up without both parents on aggression, rule breaking, and delinquency are also larger for boys than for girls. Since these traits predict both college attendance and graduation, the spread of single-parent families over the past few decades may have contributed to the growing gender gap in college attendance and graduation. The gender gap in college completion is much more pronounced among children raised by single mothers than among children raised in two-parent families.

This new research suggests that the retreat from marriage has a spill-over effect: the behavioral problems of children from broken families not only negatively affect their own educational and financial outcomes, but the outcomes of their peers. When we consider that marriage tends to decrease the chances of children being exposed to both domestic violence (the study’s selection of choice as mentioned above) and violent crimes within neighborhoods, the importance of healthy, stable marriages becomes all the more clear.

Intact families are necessary for the flourishing of children and the adults they will eventually become.

Lapp recognizes that narratives about the poor often fall into two extreme categories and that he could easily adopt one of these extremes in telling of the story of those he’s interviewed. One extreme highlights external factors and lack of resources (typically the political left), but this largely ignores the poor’s “own words about how things could have been different if they had made different choices.” The other extreme focuses “almost exclusively on these young adults’ own moral responsibilities, and downplay the cultural and economic forces and trauma clearly impinging on their lives” (typically the political right). “The true story,” Lapp says, “…is one that shows how cultural and economic forces and trauma intersect with people’s own free decisions.” To “scold the “

Lapp recognizes that narratives about the poor often fall into two extreme categories and that he could easily adopt one of these extremes in telling of the story of those he’s interviewed. One extreme highlights external factors and lack of resources (typically the political left), but this largely ignores the poor’s “own words about how things could have been different if they had made different choices.” The other extreme focuses “almost exclusively on these young adults’ own moral responsibilities, and downplay the cultural and economic forces and trauma clearly impinging on their lives” (typically the political right). “The true story,” Lapp says, “…is one that shows how cultural and economic forces and trauma intersect with people’s own free decisions.” To “scold the “