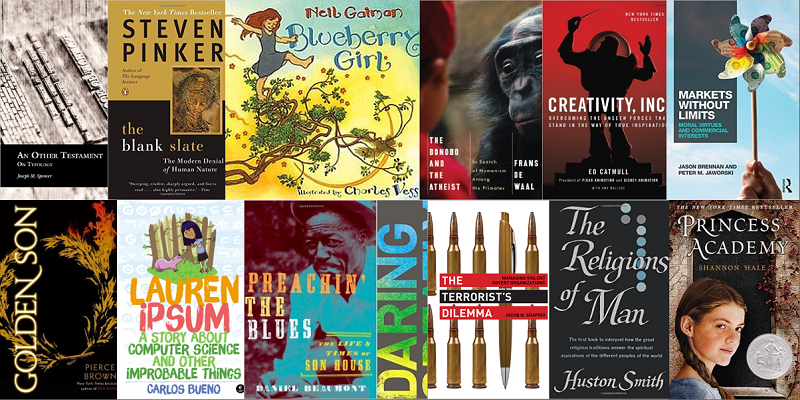

Continuing the tradition that we started last year, I asked the DR Editors to each pick their five favorite books from 2015. Once again, we’ve got a fantastic, eclectic selection of books. Without further ado, and in no particular order, here are best books that we read last year.

Walker Wright

Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead (Brené Brown)

Brown’s approach to shame and vulnerability has had a significant impact on my worldview, including how I interpret my religion. However, my exposure to her work over the last couple years was largely through her TED talks, articles, and professional counseling. I finally read a couple of her books this year, Daring Greatly being my favorite. The book is a fantastic mix of research, anecdotes, and application. The insights within it are themselves therapeutic, providing a language capable of capturing many of the turbulent emotions we experience. The result is better self-understanding and increased self-awareness. A paradigm shifting book.

Brown’s approach to shame and vulnerability has had a significant impact on my worldview, including how I interpret my religion. However, my exposure to her work over the last couple years was largely through her TED talks, articles, and professional counseling. I finally read a couple of her books this year, Daring Greatly being my favorite. The book is a fantastic mix of research, anecdotes, and application. The insights within it are themselves therapeutic, providing a language capable of capturing many of the turbulent emotions we experience. The result is better self-understanding and increased self-awareness. A paradigm shifting book.

Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration (Ed Catmull with Amy Wallace)

As a huge Pixar fan, I expected to enjoy the book. I didn’t expect it be one of the most enthralling management books I’ve ever read. Stanford’s Robert Sutton was right when he described it as, “One of the best business/leadership/organization design books ever written.” The narrative acts as both a biography of Pixar and an investigation into its organizational structure and managerial styles. The process of creativity is explored, revealing the importance of autonomy, candid discussion, and the expectation of failure. Perhaps the biggest takeaway, however, is that the collective brain is the creative brain. High-quality innovation spurs from the constant flow of information and ideas through a network of diverse people and backgrounds. Managers should read this, yes, but so should anyone interested in embarking on a creative endeavor.

As a huge Pixar fan, I expected to enjoy the book. I didn’t expect it be one of the most enthralling management books I’ve ever read. Stanford’s Robert Sutton was right when he described it as, “One of the best business/leadership/organization design books ever written.” The narrative acts as both a biography of Pixar and an investigation into its organizational structure and managerial styles. The process of creativity is explored, revealing the importance of autonomy, candid discussion, and the expectation of failure. Perhaps the biggest takeaway, however, is that the collective brain is the creative brain. High-quality innovation spurs from the constant flow of information and ideas through a network of diverse people and backgrounds. Managers should read this, yes, but so should anyone interested in embarking on a creative endeavor.

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (Jonathan Haidt)

My experience with Haidt prior to reading his book was similar to that of Brown’s above. I had watched his TED talks and lectures and read a number of his articles. Plus, he started showing up over at the libertarian site/magazine Reason. I was familiar with his Moral Foundations Theory and found his discussion of moral psychology absolutely fascinating. Yet, despite being familiar with his work, his book yielded an enormity of new, illuminating details about human nature. His emphasis on the primacy of emotions (the elephant) over reason (the rider) as well as our evolutionary nature as social creatures paints a vivid picture about what it is to be human. Given the often absurd assumptions about human nature we find in the 21st-century Western world, this is refreshingly rooted in reality. A much-needed book.

My experience with Haidt prior to reading his book was similar to that of Brown’s above. I had watched his TED talks and lectures and read a number of his articles. Plus, he started showing up over at the libertarian site/magazine Reason. I was familiar with his Moral Foundations Theory and found his discussion of moral psychology absolutely fascinating. Yet, despite being familiar with his work, his book yielded an enormity of new, illuminating details about human nature. His emphasis on the primacy of emotions (the elephant) over reason (the rider) as well as our evolutionary nature as social creatures paints a vivid picture about what it is to be human. Given the often absurd assumptions about human nature we find in the 21st-century Western world, this is refreshingly rooted in reality. A much-needed book.

Markets without Limits: Moral Virtues and Commercial Interests (Jason Brennan and Peter Jaworski)

“If you may do it for free, you may do it for money.” That is the premise of this meticulously argued book by Georgetown philosophy professors Brennan and Jaworski. Economist Bryan Caplan has identified what he calls the anti-market bias among voters and the authors demonstrate why this bias is unfounded. Most talk about the “moral limits of markets” focus on something other than the actual market. For example, a market in slaves doesn’t prove that markets are problem, but that slavery itself is wrong and would still be wrong if done for free. The authors go through the objections of various commodification critics and convincingly show that their arguments are (1) faulty in their logic and/or (2) not grounded in empirical social science. The arguments are powerful and should fundamentally change the nature of the debate. Should be the starting point for any discussion about markets and morality.

“If you may do it for free, you may do it for money.” That is the premise of this meticulously argued book by Georgetown philosophy professors Brennan and Jaworski. Economist Bryan Caplan has identified what he calls the anti-market bias among voters and the authors demonstrate why this bias is unfounded. Most talk about the “moral limits of markets” focus on something other than the actual market. For example, a market in slaves doesn’t prove that markets are problem, but that slavery itself is wrong and would still be wrong if done for free. The authors go through the objections of various commodification critics and convincingly show that their arguments are (1) faulty in their logic and/or (2) not grounded in empirical social science. The arguments are powerful and should fundamentally change the nature of the debate. Should be the starting point for any discussion about markets and morality.

An Other Testament: On Typology (Joseph Spencer)

Philosopher Joseph Spencer is one of the most careful readers of scripture in modern Mormonism and this book puts his skill on full display. A stellar combination of close textual analysis, biblical scholarship, and theology, Spencer explores the tension between two different interpretations of Isaiah within the Book of Mormon: Nephi’s collective, covenantal approach vs. Abinadi’s Christological, individualistic view. Spencer’s book is evidence of the kind of deep, intricate reading that can be accomplished through constant study of the text. What’s even better is that Spencer’s reading can accommodate both sides of the historicity debate (though perhaps leaning more favorably toward those championing historicity). One of the most engaging and enlightening books on the Book of Mormon I have ever read.

Philosopher Joseph Spencer is one of the most careful readers of scripture in modern Mormonism and this book puts his skill on full display. A stellar combination of close textual analysis, biblical scholarship, and theology, Spencer explores the tension between two different interpretations of Isaiah within the Book of Mormon: Nephi’s collective, covenantal approach vs. Abinadi’s Christological, individualistic view. Spencer’s book is evidence of the kind of deep, intricate reading that can be accomplished through constant study of the text. What’s even better is that Spencer’s reading can accommodate both sides of the historicity debate (though perhaps leaning more favorably toward those championing historicity). One of the most engaging and enlightening books on the Book of Mormon I have ever read.

Ro Givens

Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead (Sheryl Sandberg)

I know there were a lot of complaints about this book, but I say, that’s insanity. Even if you’re not in business, even if you didn’t start life in the upper class (and will never approach it), you can get insight from Sheryl’s life. Love her.

The BFG (Roald Dahl)

This book is adorbs. And hilarious. It was the first chapter book my 6 year old asked me to keep reading, and he then asked me to start it again when we finished.

Princess Academy (Shannon Hale)

Another piece of evidence that middle grade fiction > young adult fiction. The writing is better, the message is better (ie, exists), and I’m not embarrassed to admit that I like it. This book has strong female characters and is about the importance of education, cooperation, community, and friendship. #Mormon #represent

Lauren Ipsum: A Story About Computer Science and Other Improbable Things (Carlos Bueno)

A fairy tale about problem solving. Alice in Wonderland meets Computer Science (theory). Adorable and perfect. Read it myself, and now my kids are laughing along while I read it to them.

(FAQ: Yes, I like children’s lit. I read more on my own than to my kids.)

Allen Hansen

Preachin’ the Blues: The Life and Times of Son House (Daniel Beaumont)

Continuing my reading of blues biographies, I picked up this one about a man whose music electrified me when I first heard it. A feel to it which is completely out of this world. The new crop of blues biography are interested in getting behind the mythology of the blues and into the murky details of the musicians lives. House grew up in a decently educated home with a religious background, found religion, found the blues, travelled around the south quite a bit, experienced racism and oppression, worked all sorts of manual labor only somewhat removed from slavery, went to prison, moved north during the war years and was rediscovered the same year that massive race riots broke out in his city. The bigger picture of black history in 20th century America is covered from House’s perspective, so you get an idea of how an individual experienced religion, navigated racism, and responded to various challenges. Life was no monolith, especially for bluesmen rebelling against the strictures of society. There is also a sense of profound tragedy in Son House’s life, an intelligent man of significant ability who could never conquer his twin demons of alcohol and womanizing.

Continuing my reading of blues biographies, I picked up this one about a man whose music electrified me when I first heard it. A feel to it which is completely out of this world. The new crop of blues biography are interested in getting behind the mythology of the blues and into the murky details of the musicians lives. House grew up in a decently educated home with a religious background, found religion, found the blues, travelled around the south quite a bit, experienced racism and oppression, worked all sorts of manual labor only somewhat removed from slavery, went to prison, moved north during the war years and was rediscovered the same year that massive race riots broke out in his city. The bigger picture of black history in 20th century America is covered from House’s perspective, so you get an idea of how an individual experienced religion, navigated racism, and responded to various challenges. Life was no monolith, especially for bluesmen rebelling against the strictures of society. There is also a sense of profound tragedy in Son House’s life, an intelligent man of significant ability who could never conquer his twin demons of alcohol and womanizing.

The Terrorist’s Dilemma: Managing Violent Covert Organizations (Jacob N. Shapiro)

I read quite a few books on terrorism last year, but this one stands out. Shapiro looks at terrorist organizations from a management perspective. Terrorist leaders, it turns out, use Excel spreadsheets, handle time-off requests, and issue write-ups in order to run terrorist activities, but the stakes (naturally) are much higher than they would be in legitimate corporations. The tighter the control, the more the paperwork the greater the risk of being compromised. That Excel spreadsheet can cost your life if discovered, but without it you might not be able to counter waste and theft of resources or prevent operative’s violence from spinning out of control (even for terrorists there is such a thing as too much violence). As Shapiro pointedly observes, terrorists face a major personnel challenge. Someone willing to do horrible things to other human beings is not likely to be an upstanding and conscientious agent or keep violence subordinate and appropriate to achieving political goals. This weakness can be exploited to minimize the ability of terrorists to act. Shapiro analyses multiple terrorist groups from different times and places, showing this common thread, and in the process making them a little less exotic, and more banal.

I read quite a few books on terrorism last year, but this one stands out. Shapiro looks at terrorist organizations from a management perspective. Terrorist leaders, it turns out, use Excel spreadsheets, handle time-off requests, and issue write-ups in order to run terrorist activities, but the stakes (naturally) are much higher than they would be in legitimate corporations. The tighter the control, the more the paperwork the greater the risk of being compromised. That Excel spreadsheet can cost your life if discovered, but without it you might not be able to counter waste and theft of resources or prevent operative’s violence from spinning out of control (even for terrorists there is such a thing as too much violence). As Shapiro pointedly observes, terrorists face a major personnel challenge. Someone willing to do horrible things to other human beings is not likely to be an upstanding and conscientious agent or keep violence subordinate and appropriate to achieving political goals. This weakness can be exploited to minimize the ability of terrorists to act. Shapiro analyses multiple terrorist groups from different times and places, showing this common thread, and in the process making them a little less exotic, and more banal.

Strange Fruit: Why Both Sides are Wrong in the Race Debate (Kenan Malik)

You might not expect such a book to be written by someone like Kenan Malik. Malik is a British journalist born in a Muslim family in India, a philosopher of science trained in neurobiology, and a secular humanist on the political left. In the book he traces changing attitudes on race from antiquity to the present where it has become entrenched in the twin forms of scientific race realism and identity politics. He skewers race realists or essentialists, but not as much as he does anti-racists. The former conflate the issue of genetic differences with constructs of race, and the latter transformed cultural and genetic differences into dogmatic philosophy. Both reject enlightenment ideas of universality and scientific rationality. Malik is witty, thought-provoking, and has a great way of getting to core of whatever issue is under discussion.

You might not expect such a book to be written by someone like Kenan Malik. Malik is a British journalist born in a Muslim family in India, a philosopher of science trained in neurobiology, and a secular humanist on the political left. In the book he traces changing attitudes on race from antiquity to the present where it has become entrenched in the twin forms of scientific race realism and identity politics. He skewers race realists or essentialists, but not as much as he does anti-racists. The former conflate the issue of genetic differences with constructs of race, and the latter transformed cultural and genetic differences into dogmatic philosophy. Both reject enlightenment ideas of universality and scientific rationality. Malik is witty, thought-provoking, and has a great way of getting to core of whatever issue is under discussion.

The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (Margaret MacMillan)

There is fierce debate over what started the First World War, but this book poses a different question. Why did peace end? Europe was not facing its severest crisis, it actually had a good system in place for preserving peace, but it failed in 1914. There was nothing inevitable about the process, and MacMillan does a great job of unpacking the various social, intellectual and political currents which along with personal factors influenced the small group of decision-makers who ultimately chose war. The writing is very engaging and never dry, painting a remarkable portrait of Europe in the early 20th century. MacMillan knows her stuff, but isn’t afraid to be entertaining, like when she draws (an apt) comparison between Wilhelm of Germany and Toad of Toad Hall.

There is fierce debate over what started the First World War, but this book poses a different question. Why did peace end? Europe was not facing its severest crisis, it actually had a good system in place for preserving peace, but it failed in 1914. There was nothing inevitable about the process, and MacMillan does a great job of unpacking the various social, intellectual and political currents which along with personal factors influenced the small group of decision-makers who ultimately chose war. The writing is very engaging and never dry, painting a remarkable portrait of Europe in the early 20th century. MacMillan knows her stuff, but isn’t afraid to be entertaining, like when she draws (an apt) comparison between Wilhelm of Germany and Toad of Toad Hall.

Yosef Haim Brenner: A Life (Anita Shapira)

Growing up in Israel, Brenner was a legendary figure from our past, a cultural messiah of the founding generation. This is probably the narrowest-interest book of the five, but it is still superb. Brenner was born in a religious Jewish family in 19th century Ukraine, fell in love with secular Hebrew literature, and abandoned his religion. His father retaliated by making him serve in the Russian army so that his religiously-minded brother would be exempt from military service. Unsurprisingly, Brenner suffered from bouts of depression throughout his life. He still had a tremendous attachment to his people and the new Hebrew literature while his unflinching honesty and ascetic lifestyle spun a myth around him even in his lifetime. He moved to Palestine in 1909, and was murdered by an Arab mob in the 1921 riots. Shapira scrupulously avoids the myth, making Brenner’s tortured life all the more compelling.

Growing up in Israel, Brenner was a legendary figure from our past, a cultural messiah of the founding generation. This is probably the narrowest-interest book of the five, but it is still superb. Brenner was born in a religious Jewish family in 19th century Ukraine, fell in love with secular Hebrew literature, and abandoned his religion. His father retaliated by making him serve in the Russian army so that his religiously-minded brother would be exempt from military service. Unsurprisingly, Brenner suffered from bouts of depression throughout his life. He still had a tremendous attachment to his people and the new Hebrew literature while his unflinching honesty and ascetic lifestyle spun a myth around him even in his lifetime. He moved to Palestine in 1909, and was murdered by an Arab mob in the 1921 riots. Shapira scrupulously avoids the myth, making Brenner’s tortured life all the more compelling.

Monica

Blueberry Girl (Neil Gaiman, Charles Vess – illustrator)

This is a lovely book about all of the gifts a parent wishes for his or her newborn daughter, such as freedom from fear, protection from false friends, and help to help herself. Neil Gaiman wrote the book as a poem, and the rhymes and cadence make it pleasant to read to your own daughter (over and over and over). Charles Vess illustrated the poem with beautiful paintings that show girls exploring the world in a carefree, whimsical way. I was pleased to notice the girls in the paintings are different ages and races with different hairstyles and ways of dressing. I like that variety because I like to think about little girls from many walks of life examining the paintings as their parents read to them and feeling the poem is about them too.

This is a lovely book about all of the gifts a parent wishes for his or her newborn daughter, such as freedom from fear, protection from false friends, and help to help herself. Neil Gaiman wrote the book as a poem, and the rhymes and cadence make it pleasant to read to your own daughter (over and over and over). Charles Vess illustrated the poem with beautiful paintings that show girls exploring the world in a carefree, whimsical way. I was pleased to notice the girls in the paintings are different ages and races with different hairstyles and ways of dressing. I like that variety because I like to think about little girls from many walks of life examining the paintings as their parents read to them and feeling the poem is about them too.

As a Christian deconvert and secular parent, I regret that I miss out on the comfort of praying for my daughter. This book has served as a kind of substitute for me. I’ve read Blueberry Girl to my own girl dozens of times, and it’s been not just pleasant but cathartic to say out loud so many of the hopes I have for her.

Bryan Maack

The Religions of Man (Houston Smith)

One question I think every religious person should ask themselves is “Why I do I believe what I believe?” And part of answering that question is answering why you don’t believe anything else. In order to answer that question, I believe that the very best case must be made for every religion.

One question I think every religious person should ask themselves is “Why I do I believe what I believe?” And part of answering that question is answering why you don’t believe anything else. In order to answer that question, I believe that the very best case must be made for every religion.

Here’s where The Religions of Man by Huston Smith steps in. Smith gives you a sympathetic account of many major world religions–Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. The author helps you understand why so many people follow these religions earnestly. If anyone has authority to speak on this topic, Huston Smith does, having practiced Vedanta Hinduism, Zen Buddhism, and Sufi Islam for over a decade each [citation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Huston_Smith#Religious_ practice].

I will admit that many of the chapters challenged me to seriously consider why I am a Roman Catholic and nothing else. This experience inculcates a sense of humility and understanding of why people of good will hold to many different religions. But far from descending to syncretism, The Religions of Man illustrates the particular problems that religions are addressing and the diverse solutions that they offer, creating a real chance for the reader to discern among unique options.

The book was originally published in 1958. A new 50th anniversary edition, entitled “The World’s Religions,” was published in 2009 with revisions and an added section on indigenous religions.

Nathaniel Givens

I read over 100 books in 2015, but I’m going to narrow it down to just 5. That’s really hard–in the sense that I don’t like leaving good books out (and I’m leaving a lot of good books out!)–but in actuality it only took me a few minutes of going through my Goodreads reviews from 2015 to pick my top 5. Here they are:

Golden Son: Book II of The Red Rising Trilogy (Pierce Brown)

Golden Son is the second book in the Red Rising trilogy. The first book (Red Rising) was good, but it was a little violent for my tastes and also a little derivative: it was basically Ender’s Game

Golden Son is the second book in the Red Rising trilogy. The first book (Red Rising) was good, but it was a little violent for my tastes and also a little derivative: it was basically Ender’s Game + The Hunger Games (Book 1)

+ The Hunger Games (Book 1) . The second book blew me away, however. Pierce Brown took things to a new level in two ways. First: the action was non-stop from start to finish. The phrase “break neck” gets used a lot in describing the pace of a fun adventure book, but it’s never been more true than of this book. There was scene after scene where I thought for sure the characters were dead (or that the resolution would be silly), but again and again Brown pulled it off.Second: the book was much more original thoughtful than the first. This is true in terms of politics and also in terms of characterization. The cast of characters is unusually large but, thanks to the investment you put into Red Rising to get this far, you know who everybody is and how they relate to each other. Like Ender’s Game, we’re dealing with a bunch of geniuses and–like Orson Scott Card–Brown writes intelligently and thoughtfully enough for that to believable. Moreover, the moral/political aspects of the book are deep enough to be truly interesting. They aren’t just an excuse for righteous anger and action, they are really meaningful to the point where it gives you something to think about and (most importantly) really make you identify with the characters. Also: the setting. Started out pretty hackneyed (futuristic sci-fi patterned after ancient Earth mythology), but Brown kept at it so long and so seriously that the result is (1) believable and (2) distinctively his own.

. The second book blew me away, however. Pierce Brown took things to a new level in two ways. First: the action was non-stop from start to finish. The phrase “break neck” gets used a lot in describing the pace of a fun adventure book, but it’s never been more true than of this book. There was scene after scene where I thought for sure the characters were dead (or that the resolution would be silly), but again and again Brown pulled it off.Second: the book was much more original thoughtful than the first. This is true in terms of politics and also in terms of characterization. The cast of characters is unusually large but, thanks to the investment you put into Red Rising to get this far, you know who everybody is and how they relate to each other. Like Ender’s Game, we’re dealing with a bunch of geniuses and–like Orson Scott Card–Brown writes intelligently and thoughtfully enough for that to believable. Moreover, the moral/political aspects of the book are deep enough to be truly interesting. They aren’t just an excuse for righteous anger and action, they are really meaningful to the point where it gives you something to think about and (most importantly) really make you identify with the characters. Also: the setting. Started out pretty hackneyed (futuristic sci-fi patterned after ancient Earth mythology), but Brown kept at it so long and so seriously that the result is (1) believable and (2) distinctively his own.

I can’t wait to read Morning Star: Book III of The Red Rising Trilogy when it comes out in February.

when it comes out in February.

The Three-Body Problem (Cixin Liu)

This was the first time that an English-translation of a foreign language (Chinese, in this case) book won the Hugo Award for Best Novel, and boy did he deserve it! There was all kinds of drama in the Hugos in 2015, but the one thing that ended up definitively right was that this book won.

This was the first time that an English-translation of a foreign language (Chinese, in this case) book won the Hugo Award for Best Novel, and boy did he deserve it! There was all kinds of drama in the Hugos in 2015, but the one thing that ended up definitively right was that this book won.

It definitely comes from the “literary sci-fi” end of the genre, which is where you’ll find books like The Handmaid’s Tale , The Road

, The Road , or Never Let Me Go

, or Never Let Me Go . These are all books by writers who have at least one foot outside of the genre, and they aren’t well received by the folks who grew up on the Holy Trinity of Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke. But me? I love them all. I love the fusion of legit sci-fi (read: “not just time travel”) with literary sensibility, and this is perhaps one of the best examples of that sub-genre. I was hooked from the very first scene, a vivid and beautiful depiction of the chaotic internecine political clashes during the Cultural Revolution and the book never let me go. The sci-fi was serious, in that it was very intense extrapolation of actual cutting-edge theoretical physics. But it never became one of those “look at my engineering prowess!” ego-cruises that bedevil hard sci-fi (looking at you, Ringworld.) That’s because the characters were too sensitively drawn and too human for the science to overshadow them.

. These are all books by writers who have at least one foot outside of the genre, and they aren’t well received by the folks who grew up on the Holy Trinity of Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke. But me? I love them all. I love the fusion of legit sci-fi (read: “not just time travel”) with literary sensibility, and this is perhaps one of the best examples of that sub-genre. I was hooked from the very first scene, a vivid and beautiful depiction of the chaotic internecine political clashes during the Cultural Revolution and the book never let me go. The sci-fi was serious, in that it was very intense extrapolation of actual cutting-edge theoretical physics. But it never became one of those “look at my engineering prowess!” ego-cruises that bedevil hard sci-fi (looking at you, Ringworld.) That’s because the characters were too sensitively drawn and too human for the science to overshadow them.

What I’m trying to say is that it worked as sci-fi and as literature. And that’s peanut butter and chocolate, right there. It doesn’t get any better.

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (Steven Pinker)

Steven Pinker did not pull any punches! In this tour de force he takes on the reigning social science model head-on without apologies and also without taking prisoners. He outlines the social science model as having three essential premises: the Blank Slate (i.e. human nature is socially constructed rather than biologically determined), the Noble Savage (i.e. the trendy obsession with “all natural” foods and opposition to vaccines) and the Ghost in the Machine (there’s more to the mind than the brain and bod). He describes the dogmatic defense of these views in the social sciences this way:

Steven Pinker did not pull any punches! In this tour de force he takes on the reigning social science model head-on without apologies and also without taking prisoners. He outlines the social science model as having three essential premises: the Blank Slate (i.e. human nature is socially constructed rather than biologically determined), the Noble Savage (i.e. the trendy obsession with “all natural” foods and opposition to vaccines) and the Ghost in the Machine (there’s more to the mind than the brain and bod). He describes the dogmatic defense of these views in the social sciences this way:

This is the mentality of a cult, in which fantastical beliefs are flaunted as proof of one’s piety. That mentality cannot coexist with an esteem for the truth, and I believe it is responsible for some of the unfortunate trends in recent intellectual life.

The rest of the book is a long, empirically-based attack on all three of these fallacies and, secondarily, an attempt to explain why they are not actually necessary to defend the kind of classical liberal values they are often employed to defend. This is one of Pinker’s most important points: if you defend equality on the basis of the Blank Slate (which is by far the most prevalent philosophical basis for feminism, etc.) then you are actually endangering the value you’re trying to defend. Because the blank slate is false. Gender is not (entirely) a social construction. Men and women are biologically different in meaningful ways that go beyond just anatomy. And if you have erected your theory of equality on that false foundation, then when it gets destroyed–and it will get destroyed eventually–the value you were trying to defend is going to get taken down with it.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that I don’t agree with Pinker all down the line. When he stops talking psychology or neuroscience and starts talking political philosophy he loses me on several occasions. In addition, I find Thomas Nagels repudation of reductionist materialism entirely persuasive, and that means that I find Pinker’s assault on the Ghost in the Machine to be, ultimately, a failure. But that’s his least-important point (there’s a reason the book is named for the Blank Slate and not the Ghost in the Machine) and, in any case, I do think that his critique of the Ghost in the Machine as it relates to the standard model of social science theory has traction. In other words, the kind of dualism he is attacking is unsustainable. I agree him there. But the absolutist physical reductionism he erects in its place is also a failure.

Still, this was great book, strongly argued and full of interesting information that I’m continuing to assimilate into my view of myself and the world.

The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates (Frans de Waal)

This is another brilliant book that I love to both agree and disagree with. Primatologist Frans de Waal has a pretty straightforward objective: demonstrate empirically that the foundations of moral behavior are found in primates (and other mammals). Well, that’s the first half, anyway, and it’s the half that he gets resoundingly right. The experiments and stories–both first-person and collected from others–are fascinating reading and deeply impactful.

This is another brilliant book that I love to both agree and disagree with. Primatologist Frans de Waal has a pretty straightforward objective: demonstrate empirically that the foundations of moral behavior are found in primates (and other mammals). Well, that’s the first half, anyway, and it’s the half that he gets resoundingly right. The experiments and stories–both first-person and collected from others–are fascinating reading and deeply impactful.

I was particularly struck, for example, by his descriptions of how primates care for each other, including the disabled. He described one young rhesus monkey that was born with a condition similar to Down syndrome, and how that monkey was cared for by the rest of the troop and tolerated when she did unusual things (like try to pick a fight with the alpha male) that would have gotten any other monkey a severe beating. He also pointed out fossil evidence that Neanderthals also cared for the disabled who could offer nothing in return.

The book never veered into sentimentality, however. De Waal’s view of primates is clear-eyed, and this led to additional insights into the nature of social order and its relationship to the threat of the violence. He wrote in one passage, however, that after observing a tribe of chimpanzees wait patiently for their turn to use a nut-cracking station to crack nuts that were too tough to crush with their teeth:

I was struck by the scene’s peacefulness, but not fooled by it. When we see a disciplined society, there is often a social hierarchy behind it. This hierarchy, which determines who can eat or mate first, is ultimately rooted in violence… A social hierarchy is a giant system of inhibitions, which is no doubt what paved the way for human morality, which is also such a system.

As with Pinker, however, I disagreed with some of de Waal’s conclusions. In particular, he believed that if you can show the origins of moral behavior then you have found the origins of morality itself. This is a major flaw, and also happens to be another one that is addressed by Thomas Nagel. It’s the basic is/ought fallacy (a topic de Waal addressed explicitly but did not handle satisfactorily) and the rebuttal to it is the same rebuttal to pretty much all forms of relativism: you can’t argue for relativism without enacting objectivism. If you say, “subjectivity holds,” you’ve already made a contradictory, objective statement.

Merely because you can show how a thing arises through evolution doesn’t get you out of this problem. You could explain how humans came to have the ability to reason objectively, but that wouldn’t mean that logic and math were suddenly subjective. It would just prove that somehow evolution managed to get us in touch with non-contingent, objective reason. Same idea here: you can explain how humans came to behave morally or even to understand and think about morality, but it’s a colossal mistake to think that, in so doing, you have proved that morality is “constructed” or in any way subjective any more than reason or logic are. (For fun: let someone try to reason you out of the position that reason is objective. See how that works? It’s a non-starter.)

Surprised by Scripture: Engaging Contemporary Issues (N. T. Wright)

This was one of the first books I read in 2015, and it feels like I read it even longer ago than that, but Goodreads doesn’t lie. I finished it on Jan 9, 2015. This one was a huge eye-opener for me. I am very religious, but I come from a Mormon background, and we don’t always have the most sophisticated grasp on the Bible (relative to other Christians) because we split our attention between the Bible and our unique books of scripture: the Book of Mormon in particular.

This was one of the first books I read in 2015, and it feels like I read it even longer ago than that, but Goodreads doesn’t lie. I finished it on Jan 9, 2015. This one was a huge eye-opener for me. I am very religious, but I come from a Mormon background, and we don’t always have the most sophisticated grasp on the Bible (relative to other Christians) because we split our attention between the Bible and our unique books of scripture: the Book of Mormon in particular.

So for me to see how N. T. Wright connected all kinds of contemporary political debates to the text of the Bible was incredibly mind-expanding. It really deepened by respect for the Bible and also for the traditions of Protestant and Catholic Christianity. It was not really a surprising experience–I read the book precisely because I already knew I was weak on Biblical understanding–but it was still a humbling one in the best way possible. Humbling because when you see a real expert at work you are too distracted by the beauty and skill of their craft and knowledge to feel bad about your shortcomings.

N. T. Wright’s writing style is engaging and this remains an incredibly important book for me, with a serious and ongoing impact on how I view my own faith.

And now, because I can’t resist, honorable mention. Some additional great fiction I read this year includes:

Cibola Burn (The Expanse) – The fourth book in The Expanse is definitely the best, and is significantly better than the first three. Five was also quite good, and I can’t wait for six.

– The fourth book in The Expanse is definitely the best, and is significantly better than the first three. Five was also quite good, and I can’t wait for six.

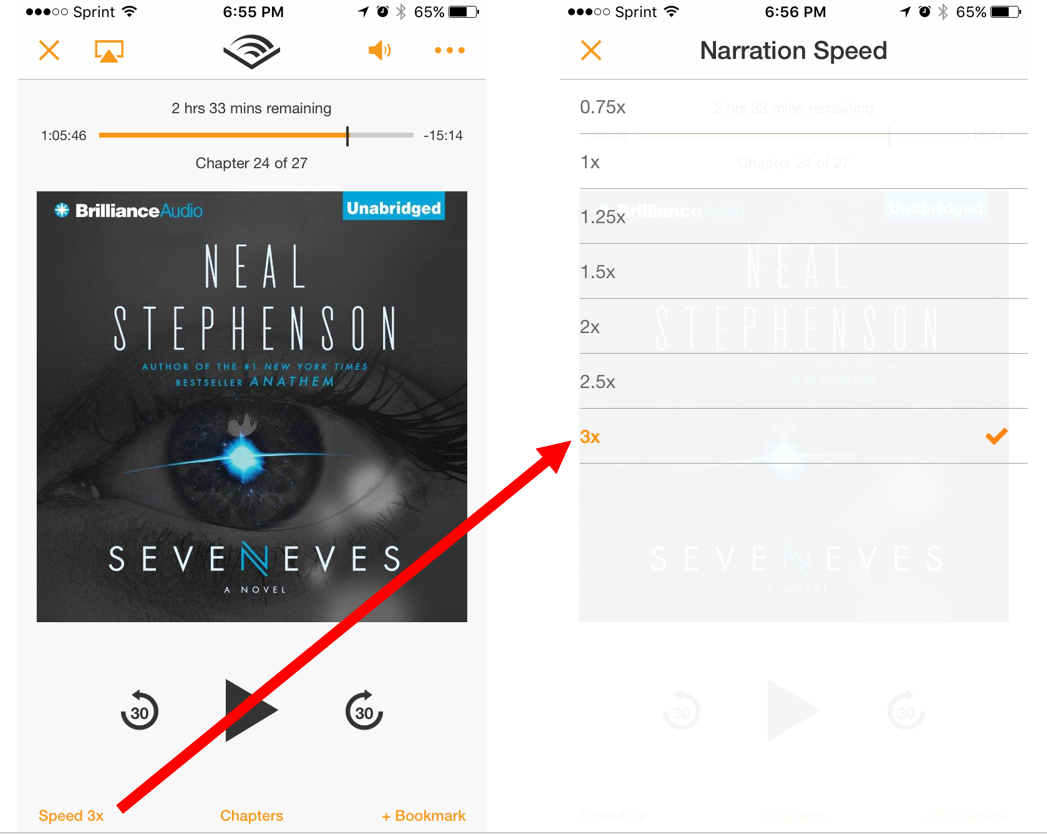

Half-Resurrection Blues: A Bone Street Rumba Novel – This book blew me away. The prose was my favorite part. In fair warning, there is a lot of vulgarity, but for some reason it didn’t phase me as it usually did. I had to stop the audiobook (which is narrated by the author, fantastically) on more than one occasion just to save what I’d read. (Also: just noticed that the sequel Midnight Taxi Tango

– This book blew me away. The prose was my favorite part. In fair warning, there is a lot of vulgarity, but for some reason it didn’t phase me as it usually did. I had to stop the audiobook (which is narrated by the author, fantastically) on more than one occasion just to save what I’d read. (Also: just noticed that the sequel Midnight Taxi Tango is out!)

is out!)

Son of the Black Sword (Saga of the Forgotten Warrior) – Larry Correia started as one of those self-publishing sensations who finds a diehard audience (in this case, gun nuts who want to read a mashup of a gun catalog and a zombie-slaying video game) and makes it big. The big question for me is often: what happens next. As you can tell, I wasn’t ever the biggest fan of Monster Hunter International

– Larry Correia started as one of those self-publishing sensations who finds a diehard audience (in this case, gun nuts who want to read a mashup of a gun catalog and a zombie-slaying video game) and makes it big. The big question for me is often: what happens next. As you can tell, I wasn’t ever the biggest fan of Monster Hunter International , but I thought his other series (starting with Hard Magic (The Grimnoir Chronicles)

, but I thought his other series (starting with Hard Magic (The Grimnoir Chronicles) ) was really great. Well, this is his third new series and it is–without any doubt–the best. His writing, plotting, characterization: everything has progressed. This is a guy who, in some ways, got lucky, but then he made it count.

) was really great. Well, this is his third new series and it is–without any doubt–the best. His writing, plotting, characterization: everything has progressed. This is a guy who, in some ways, got lucky, but then he made it count.

The Cinder Spires: the Aeronaut’s Windlass – Jim Butcher is still my favorite living author, but if The Dresden Files

– Jim Butcher is still my favorite living author, but if The Dresden Files are not your cup of tea: you should still try this one. The style is totally different, so is the setting, so is the plot, so are the characters. It’s an amazing post-apocalyptic forgotten-technology-as-magic with a crew of unforgettable and awesome characters.

are not your cup of tea: you should still try this one. The style is totally different, so is the setting, so is the plot, so are the characters. It’s an amazing post-apocalyptic forgotten-technology-as-magic with a crew of unforgettable and awesome characters.

In the past couple of years, I’ve read several books that deal with the origins of human society: Frans de Waal’s The Bonobo and the Atheist, Matt Ridley’s The Origins of Virtue, Francis Fukuyama’s Origins of Political Order, and Yuval Harari’s Sapiens are just a few examples.