The Hugo award nominations will be announced publicly this Saturday.[ref]Why on earth they announce the ballot the Saturday before Easter is beyond me. Scalzi has explained how dumb this policy is, but apparently nobody is listening.[/ref] You might remember the Hugo awards vaguely from last year when there was a giant political kerfuffle. The way the Hugos work, anyone who wants to attend WorldCon or even just pay $40 for a non-attending supporting membership is eligible to nominate a work and vote for it. Historically, only about 10-20% of the approximately 10,000 WorldCon attendees have actually voted, however, and as a result science fiction’s most prestigious literary awards[ref]There are also awards in other categories, such as graphic novel, film, or even related academic / critical works, but the best novel, best novella, etc. awards are the headliners.[/ref] are decided upon by a very small group of people.

So last year, bombastic arch-conservative Larry Correia decided to prove that this small population of voters was not very representative of fandom generally and, more to the point, that there was actually an insular, politically rigid clique dominating the Hugos. To make his point, he suggested an alternate slate of nominees (mostly from the right end of the political spectrum) and then encouraged his fans to purchase memberships and vote. This initiative was called Sad Puppies 2. His fans responded in great numbers, several of his nominees made it onto the ballot, and–although none received an award–the entire sci-fi community was riven by controversy and anger. At Corriea (for politicizing the Hugos) or at the social justice advocates who opposed him (for politicizing the Hugos even earlier.)

So last year, bombastic arch-conservative Larry Correia decided to prove that this small population of voters was not very representative of fandom generally and, more to the point, that there was actually an insular, politically rigid clique dominating the Hugos. To make his point, he suggested an alternate slate of nominees (mostly from the right end of the political spectrum) and then encouraged his fans to purchase memberships and vote. This initiative was called Sad Puppies 2. His fans responded in great numbers, several of his nominees made it onto the ballot, and–although none received an award–the entire sci-fi community was riven by controversy and anger. At Corriea (for politicizing the Hugos) or at the social justice advocates who opposed him (for politicizing the Hugos even earlier.)

Fast forward to a new year and a new Hugo season, and moderate conservative Brad Torgersen (whom Correia has affectionately referred to as “the Powder Blue Care Bear” among conservative sci-fi authors) decided to spearhead Sad Puppies 3. And, as I mentioned at the outset, the results of this third initiative will be announced on Saturday. Leading up to that announcement, however, Teresa Nielsen Hayden published an absolutely astonishing post on the blog she runs with her husband.

Fast forward to a new year and a new Hugo season, and moderate conservative Brad Torgersen (whom Correia has affectionately referred to as “the Powder Blue Care Bear” among conservative sci-fi authors) decided to spearhead Sad Puppies 3. And, as I mentioned at the outset, the results of this third initiative will be announced on Saturday. Leading up to that announcement, however, Teresa Nielsen Hayden published an absolutely astonishing post on the blog she runs with her husband.

The Haydens, just so you’re aware, are prominent members of the social justice advocacy clique that vehemently opposed Sad Puppies 2 (under Correia) and 3 (under Torgersen). It may or may not be worth noting that, between the two of them (both editors at Tor), they have one Hugo award and fourteen nominations. In any case, her post was titled Distant thunder, and the smell of ozone, and here it is in its entirety[ref]There are going to be lots more quotes from Hayden. They all come from comments she made to this post.[/ref]:

I’ve been keeping an ear on the SF community’s gossip, and I think the subject of this year’s Hugo nominations is about to explode.

Let me make this clear: my apprehensions are not based on insider information. I’m just correlating bits of gossip. It may help that I’ve been a member of the SF community for decades.

If the subject does blow up, I may write about it in this space. In any event, watch that space.

I’ll be honest: I didn’t get the big deal when I first read that. It was only after reading a variety of pieces by Correia, Torgersen, and Sarah Hoyt (another conservative / libertarian sci-fi author) that I realized what was going on. And then I was both shocked and a little excited. Let me break it down for you.

Sad Puppies 3 is Working

Corriea explained the most plausible explanation for where Hayden got her information about the unannounced Hugo slate. First, he quoted Hayden’s description of how the notification process for the Hugo nominations works:

When you’re nominated for a Hugo, you’re contacted ahead of time by the Hugo administrators, who check to make sure you’ll accept nomination. If they’re going to have to add the next-highest nominee in a category, they want to do it before the general public sees the ballot, so that no one knows who’s the lowest-ranked nominee.

Then he drew the obvious conclusion: “Teresa is worried. Why? Because as an insider, the people she already knew were SUPPOSED to get Hugo nominations haven’t been contacted… ” This explains Hayden’s statement that “I think they’ve succeeded in f*cking up the ballot beyond all expectation.” If nobody in her clique is getting one of those phone calls, she must assume that the Sad Puppies 3 slate is going to dominate the final ballot. The ironic thing, of course, is that she outlined the Hugo process in order to complain that Sad Puppies organizers might coordinate to reverse-engineer the approximate votes:

If the SPs got all or most of their slate onto the ballot, and those people had their nominations confirmed by the Hugo administrators, and they were comparing notes behind the scenes, they’d be uniquely able to reconstruct most or all of the final ballot.

Apparently “comparing notes behind the scenes” is bad when the Sad Puppies folks do it, is perfectly justifiable when Hayden coordinates with her buddies (and then writes public, panic-tinged posts) doing the exact same thing.

The Truth is Coming Out

In another comment to the same post, Hayden wrote that:

Why are people talking about what would happen if everyone who reads SF voted in the Hugos? IMO, it’s not a relevant question. The Hugos don’t belong to the set of all people who read the genre; they belong to the worldcon, and the people who attend and/or support it. The set of all people who read SF can start their own award.

This is a very abrupt departure from rhetoric back in 2014. At that time, the ruling clique still had the power to kick the Sad Puppies around. After all, some of the Sad Puppies 2 works made it into the ballot, but none of them actually won an award. In fact, most of the prominent awards that year (Hugos and others) were a sweeping success for the social justice crowd, and there was much celebration. In those days, they emphasized the universality of the Hugos as the pre-eminent sci-fi award bar none. This was the genre’s award. But now that they sense they are losing control, they are suddenly eager to denigrate the awards and start gatekeeping overtly.

I should add that Hayden clarified her remark subsequently, writing that “When I say the Hugos belong to the worldcon, I’m talking about the literal legal status of the award.” It’s hard to see that backpedaling as genuine, however.

There was an even more remarkable admission from Hayden in the comments, however. She stated that

Indications are that a fair number of them [nominees on the Sad Puppy slate who got onto the ballot], maybe a majority, are respectable members of the SF community who, for one reason or another, are approved of by the SPs while not being ideologically Sad Puppies themselves.

First, let’s take a moment to ponder where she gleaned the identities of the SP folks who made it into the ballot. Correia’s theory explains how she could know the quantity, but if she actually knows who they are then her protests of not having “insider information” ring entirely hollow.

But what’s more important is that she is willingly conceding that the SP slate is not ideological. More on that in the next section. For now, let’s focus on why she is making the effort to separate the goats from the sheep, as it were, and point out that some of the folks put forward by SP3 aren’t really bad guys: You can’t call the dogs off of some folks without implicitly admitting that you’re happy to have them sicced on other folks. This is a big give-away from the social justice folks. She’s tacitly admitting what the Sad Puppies folks have always been alleging: that if you don’t toe the ideological line they will savage your reputation and torpedo your career. Sarah Hoyt, picking up on exactly this logic, wrote a powerful first-hand account of what it is like to live in that climate of fear: All The Scarlet Letters. Remember that the Haydens are editors. Teresa is a consulting editor, but her husband Patrick is Manager of Science Fiction, both for Tor which is one of the biggest sci-fi publishers out there. Then try to keep in mind how absolutely cutthroat the writing industry is: making your living as an author is the dream of a millions and the reality of a privileged few. Only a tiny fraction of authors out there (like Larry Correia, for instance, who was a self-publishing phenomenon and can thumb his nose at the publishing industry) are free to speak their minds without worrying about devastating ramifications for their careers. For folks who wield as much institutional and corporate power as the Haydens do to be so unabashedly political is frightfully immoral, but hey: at least they’re not hiding it anymore.

There’s Reason for Hope

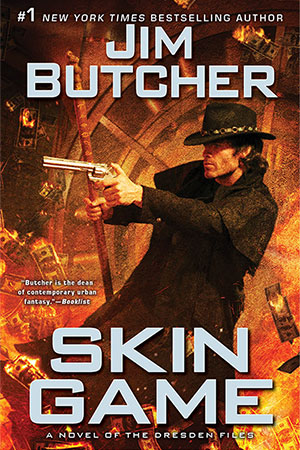

Let me backtrack a minute to talk about what I think is really the most important fact we can glean from Hayden’s comments: Sad Puppies 3 is a diverse slate. Sad Puppies 2 was not, and Correia made no bones about it. But Torgersen’s slate is a grab-bag that includes authors from across the political spectrum. Rather than attempt to prove how biased the typical Hugo voters were, Torgersen’s goal is to rehabilitate the awards by de-politicizing them. Pretty much the only criteria for his list was that a writer (1) have written something really good and (2) not be the kind of author who would usually be up for an award. A great example of this is Jim Butcher. Butcher is my favorite living author, and is best known as the man behind the Dresden Files, one of the all-time best-selling urban fantasy series. He is being nominated in the best novel category for Skin Game, which is his fifteenth novel in that series (and one of his best, in my opinion.) The last seven or eight consecutive novels in the series have all hit the NYT Bestseller List as soon as they come out. Butcher has, with one exception, never spoken out publicly about politics or controversial current events. Butcher is exactly the kind of guy who I think deserves an award, and also exactly the kind of guy who would never have stood a chance under the old regime.

Let me backtrack a minute to talk about what I think is really the most important fact we can glean from Hayden’s comments: Sad Puppies 3 is a diverse slate. Sad Puppies 2 was not, and Correia made no bones about it. But Torgersen’s slate is a grab-bag that includes authors from across the political spectrum. Rather than attempt to prove how biased the typical Hugo voters were, Torgersen’s goal is to rehabilitate the awards by de-politicizing them. Pretty much the only criteria for his list was that a writer (1) have written something really good and (2) not be the kind of author who would usually be up for an award. A great example of this is Jim Butcher. Butcher is my favorite living author, and is best known as the man behind the Dresden Files, one of the all-time best-selling urban fantasy series. He is being nominated in the best novel category for Skin Game, which is his fifteenth novel in that series (and one of his best, in my opinion.) The last seven or eight consecutive novels in the series have all hit the NYT Bestseller List as soon as they come out. Butcher has, with one exception, never spoken out publicly about politics or controversial current events. Butcher is exactly the kind of guy who I think deserves an award, and also exactly the kind of guy who would never have stood a chance under the old regime.

If the victory of SP3 just meant a palace coup where one clique replaced another, that would be nothing to celebrate. And so you can see that I’ve saved the best for last. I’m not a partisan at heart, and the idea of the Hugos moving away from the ghetto of political insularity and becoming more mainstream (at least as far as sci-fi goes) is great. Not everything is coming up roses, of course. Correia, Hoyt, Torgersen, and others seem to think that nothing matters other than fun and popularity. I certainly think enjoyment matters, but I don’t think it’s the only metric that should be considered. I think sometimes important works–works that deserve recognition and awards–aren’t fun or enjoyable in any usual sense. But that is exactly the kind of quibbling I’d like to see happen where the Hugos are concerned instead of this knock-down, to-the-knife, existentialist ideological struggle that is happening right now.

There was a time when I would buy any book that had won a Hugo award without knowing a single other fact about the book or the author. That was all it took. Once I started reading them systematically, I learned quickly that there were a lot of duds in there as well. The Hugo system has never been perfect, and that’s fine. But these days sci-fi as a literary genre is struggling and the most important award is under a cloud of suspicion and animosity. I’d love to see some improvement and Hayden’s post–and her subsequent comments and the analysis from Correia, Torgersen, Hoyt and others[ref]like Michael Z. Williamson and Matthew Bowman[/ref]–have finally given me some hope.