_0.jpg)

Trump wants to “renegotiate” or even withdraw from it. Clinton is up for “adjusting” it. With trade coming under fire (even from previous supporters), it is no wonder that NAFTA has taken some heat. But what do experts says about the economic impact of NAFTA? According to an excellent brief by the Council on Foreign Relations,

Economists largely agree that NAFTA has provided benefits to the North American economies. Regional trade increased sharply (PDF) over the treaty’s first two decades, from roughly $290 billion in 1993 to more than $1.1 trillion in 2016. Cross-border investment has also surged, with U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) stock in Mexico increasing in that period from $15 billion to more than $100 billion.

Admittedly, “experts also say that it has proven difficult to tease out the deal’s direct effects from other factors, including rapid technological change, expanded trade with other countries such as China, and unrelated domestic developments in each of the countries.” And like any trade deal, there is debate over “NAFTA’s legacy on employment and wages, with some workers and industries facing painful disruptions as they lose market share due to increased competition, and others gaining from the new market opportunities that were created.”

But what has happened to the U.S. economy since NAFTA?:

In the years since NAFTA, U.S. trade with its North American neighbors has more than tripled, growing more rapidly than U.S. trade with the rest of the world. Canada and Mexico are the two largest destinations for U.S. exports, accounting for more than a third of the total. Most estimates conclude that the deal had a modest but positive impact on U.S. GDP of less than 0.5 percent, or a total addition of up to $80 billion dollars to the U.S. economy upon full implementation, or several billion dollars of added growth per year.

Such upsides of trade often escape notice, because while the costs are highly concentrated in specific industries like auto manufacturing, the benefits of a deal like NAFTA are distributed widely across society. Supporters of NAFTA estimate that some fourteen million jobs rely on trade with Canada and Mexico, while the nearly two hundred thousand export-related jobs created annually by the pact pay 15 to 20 percent more on average than the jobs that were lost.

Furthermore, “economists like Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Cathleen Cimino-Isaacs of the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) emphasize that increased trade produces gains for the overall U.S. economy. Some jobs are lost due to imports, but others are created, and consumers benefit significantly from the falling prices and often improved quality of goods created by import competition. A 2014 PIIE study of NAFTA’s effects found that about 15,000 jobs on net are lost each year due to the pact—but that for each of those jobs lost, the economy gains roughly $450,000 in the form of higher productivity and lower consumer prices.” Interesting enough, NAFTA may have “helped the U.S. auto sector compete with China. By contributing to the development of cross-border supply chains, NAFTA lowered costs, increased productivity, and improved U.S. competitiveness. This meant shedding some jobs in the United States as positions moved to Mexico, he argues, but without the pact, even more would have otherwise been lost.”

Many critics, however, focus less on the U.S. and more on Mexico. How has the country south of the border done since NAFTA?:

NAFTA gave a major boost to Mexican farm exports to the United States, which have tripled since NAFTA’s implementation. Hundreds of thousands of auto manufacturing jobs have also been created in the country, and most studies have found (PDF) that the pact had a positive impact on Mexican productivity and consumer prices.

NAFTA was “the continuation of a decade of economic liberalization that saw [Mexico] transition from one of the world’s most protectionist economies to one of the most open to trade. Mexico had reduced many of its trade barriers upon joining the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the precursor to the WTO, in 1986, but still had a pre-NAFTA average tariff level (PDF) of 10 percent. Mexican policymakers saw NAFTA as an opportunity to both accelerate and “lock in” these hard won reforms to the Mexican economy.” Unfortunately, “Mexican unemployment also rose, which some economists have blamed on NAFTA for exposing Mexican farmers, especially corn producers, to competition from heavily subsidized U.S. agriculture.” However, many experts argue that

Mexico’s recent economic performance has been affected by many non-NAFTA factors. The 1994 devaluation of the peso drove Mexican exports, while competition with China’s low-cost manufacturing sector (PDF) likely depressed growth. Unrelated public policies, such as land reform, made it easier for farmers to sell their land and emigrate. As UCSD’s Hanson has argued (PDF), Mexico’s struggles have largely domestic causes: poorly developed credit markets, a large and low-productivity informal sector, and dysfunctional regulation.

Overall, as economist Douglas Irwin summarizes,

NAFTA has promoted the growth of a middle class in Mexico that now includes nearly half of all households. And since 2009, more Mexicans have left the United States than have come in. In the two decades since NAFTA went into effect, Mexico has been transformed from a clientelistic one-party state with widespread anti-American sentiment into a functional multiparty democracy with a generally pro-American public. Although it has suffered from drug wars in recent years (a spillover effect from problems that are largely made in America), the overall story is one of rising prosperity thanks in part to NAFTA.

I expect anti-foreign bias from voters. The problem is that smart politicians will say stupid things to appeal to these voters. I just hope the policies don’t match the rhetoric.

With skittles and terrorists in the news, it might be worth assessing the risks that immigrants pose to U.S. natives. How likely are Americans to be killed by a terrorist attack committed by a foreigner? A new policy analysis from the Cato Institute finds that the chances are vanishingly small:

With skittles and terrorists in the news, it might be worth assessing the risks that immigrants pose to U.S. natives. How likely are Americans to be killed by a terrorist attack committed by a foreigner? A new policy analysis from the Cato Institute finds that the chances are vanishingly small:

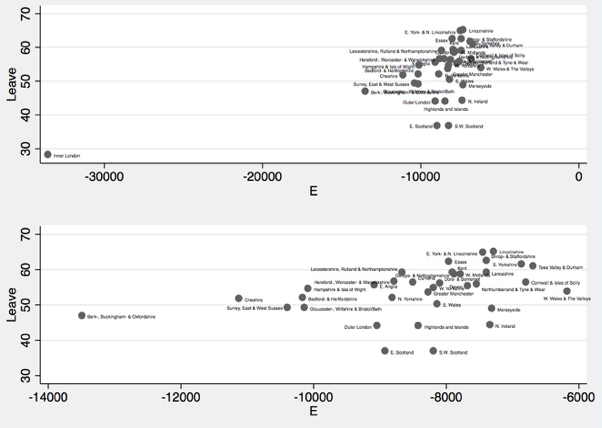

The researchers also found that “an increase in GDP per capita of €5,000…will lower the share of the leave vote by 0.55%. An increase of 5% in the share of the population over the age of 65…will increase the leave vote by 3.3%. A 5% increase in the share of the population with low education…will increase the leave vote by 4.8%.”

The researchers also found that “an increase in GDP per capita of €5,000…will lower the share of the leave vote by 0.55%. An increase of 5% in the share of the population over the age of 65…will increase the leave vote by 3.3%. A 5% increase in the share of the population with low education…will increase the leave vote by 4.8%.”_0.jpg)