Political polarization is bad enough, but sometimes partisan arguments are worse than merely polarizing. One example of this is the response to the controversial topic of political correctness and so-called “social justice warriors.”

Now, I’m not a huge fan of the term “social justice warriors” because—as a term that was initially a pejorative and is still primarily used that way—it carries a lot of baggage. But I do think that concerns about political correctness are legitimate, and I documented a lot of thinkers (primarily from the American left) who have agreed in recent months in Difficult Run’s most widely read article of 2015: When Social Justice Isn’t About Justice. This view—that political correctness, social justice activism, microagressions, tolerance, etc—have gone a little too far seems to be an emerging consensus. But there are still holdouts.

Not surprisingly, the holdouts come from within the social justice movement itself. One prominent, sympathetic voice is John Scalzi. He’s a best-selling, award-winning science fiction author who famously signed a multi-million-dollar publishing deal with Tor last year.[ref]Big enough to get its own article in the New York Times, the LA Times, and other venues.[/ref] He’s a prominent, influential voice on social justice issues, and according to him—and thousands who agree—there is no conceivable, legitimate concern to be had on this topic. For example, back in 2014, he wrote that:

“Political Correctness” is a catchphrase which today means one of two things. The first is, “I have done no substantial thinking on this topic in at least twenty years and therefore anything I say past this point cannot be treated with any seriousness.” The second is “It is more important for me to continue my ingrained bigotry than it is for you not to be denigrated or offended by my bigotry, because I am lazy and do not wish to be bothered.” If in fact you do not intend to convey either of these two things, you should not use, nor sign on to a document which uses, the phrase “political correctness.”

In November 2015, at precisely the time that opinion across much of the spectrum of American politics was starting to really take political correctness seriously as a threat, he wrote:

I’m always embarrassed for the people who use these phrases [“political correctness” and “social justice warriors”] thinking they’re cutting, when in fact what they signal to the rest of the world is that the utterer is dog-whistling to a low-wattage, bigoted rabble in lieu of making an actual argument.

You can immediately see the polarization and absolutism of Scalzi’s statements. If we take Scalzi’s argument at face value then we must write off folks like Andrew Sullivan, John McWhorter, Jeannie Suk, Jonathan Chait, Laura Kipnis, Asam Ahmad, Damon Linker, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt[ref]These are the folks I quoted in When Social Justice Isn’t About Justice [/ref] as ignorant bigots. That’s a pretty diverse list of gay and straight, male and female, white and black thinkers (almost none of whom are conservative or Republican), but in one fell swoop Scalzi says you can ignore anything they say. Which is the whole point: you can make the world a much simpler place by inventing reasons to completely ignore your opponents. This is what political polarization is all about. We’ve seen this before.

But when we look at the specifics of Scalzi’s argument, we see another problem. The key concept in Scalzi’s argument is the concept of dog whistling. A dog whistle is “a type of whistle that emits sound in the ultrasonic range, which people cannot hear but some other animals can, including dogs and domestic cats, and is used in their training.”[ref]Quote is from Wikipedia, which notes that it is also known as a “silent whistle.”[/ref] So, in politics, the idea of dog whistling is that someone disguises racism behind a veneer of apparently neutrality. For example, they will talk about “thugs” (when discussing issues of race and crime, perhaps) as a stand in for just using the n-word. This accusation is true. It is a real thing that really happens.

The problem is that Scalzi isn’t leveling the accusation against a particular thing said by a particular person in a particular context. He is saying that anyone who says anything in any context about political correctness or social justice warriors is engaging in dog whistling.

Intended or not, the inevitable consequence of this move is that it subjectifies arguments. Making an argument about a person’s motivations or private beliefs is always tricky, but in most cases we can build a case by using publicly available, objective facts like their words, their behavior, the consequences of their actions, and so forth. But that’s not possible when we make categorical statements about the motivations and private beliefs of a wide range of people without any recourse to external facts. The only way to enact the total dog whistle accusation as Scalzi does is to abandon objectivity.

The case for abolition relied on objective claims like all people deserve human rights and human rights are incompatible with slavery as an institution. The 20 century civil rights movement also relied on objective claims such as segregation is incompatible with genuine racial equality. But the all-encompassing dog whistle accusation eschews recourse to any publicly available, objectively valid facts and so eschews objectivity itself.[ref]This is a common theme in modern social justice activism, by the way. Microaggressions are essentially subjective, although in that case it’s not the alleged intention of the microaggressor that matters, but the perceptions of the microaggrieved.[/ref]

Why does this matter? It matters because once an argument becomes subjective, it no longer makes sense to talk about who is more correct. Instead, arguments inevitably devolve into contests to see who is more powerful. When objective truth is no longer a recourse, all that remains is appeal to power. [ref]This is why so much contemporary social justice activism revolves around mass-shaming. It only takes one person to present a true argument, but it takes a mob to properly browbeat someone. You could argue that it takes a lot of people to amplify a true argument, but that clearly doesn’t apply to mass-shamings. If there’s just a single person being subjected to a massive barrage of negative attacks, clearly disseminating information broadly is not the primary objective. I’m also not saying the left invented mass shaming or has the monopoly on it, but it’s certainly distinctive of contemporary social justice activism.[/ref]

This makes the dog whistle accusation an ultimately self-defeating tool from the standpoint of genuine concern for social justice, because once the argument becomes a question of power, it is a foregone conclusion that it can no longer constitute a genuine challenge powers in high places. You cannot speak subjective truth to power because subjective truth is power.

The practical reality is that the ultimate consumers of social justice activism are nice, college-educated, open-minded, prosperous, white Americans who are desperate to find the magic words to say to absolve themselves of any perceived guilt from profiting off of historical exploitation or collaborating in ongoing, systemic oppression. Social justice activism, unmoored from sternly objectivist claims, cannot resist the universal solvent of American consumerism and is already far on its way to becoming just another luxury good. Social justice arguments rooted in subjectivism are no harder for elites to absorb and appropriate than any other cultural artifact, and when that happens the tactics, rhetoric, and infrastructure of social justice are deployed to serve the interests of those elites rather than to challenge them. This is true even when social justice ends up being deployed against minorities. Weapons, even rhetorical ones, don’t care who they are aimed at.

Consider Conor Friedersdorf’s recent Atlantic piece: Left Outside the Social-Justice Movement’s Small Tent. The story describes Mahad Olad’s journey into and then estrangement from social justice activism. Why? He had the temerity to question trigger warnings and attempts to shut down conservative speakers. The result? “I was accused of being outrageously insensitive and apparently made three activist cohorts have traumatic breakdowns,” (for questioning trigger warnings) and “I was accused of being a ‘respectable negro,’ ‘uncle tom,’ ‘local coon’ and defending university officials to continue to ‘systemically oppress minorities,” (for questioning silencing of conservative speakers).

This is just one example of social justice turning against minorities, but there are plenty more. There are articles like That awkward moment when I realized my white “liberal” friends were racists and The Unchecked Racism Of The Left And The Platinum Rule and The Disturbing Story Of Widespread Sexual Assault Allegations At A Major Progressive PR Firm and What Happens When a Prominent Male Feminist Is Accused of Rape?. [ref]Note that, predominantly, these examples do not rely on subjectivist claims. Rape and sexual assault, unlike universal dog whistles and microaggressions, are not subjective.[/ref]

As long as the dog whistle accusation is used as a blanket condemnation of all who have the temerity to question social justice activism and political correctness, social justice will be subjectified and therefore vulnerable to subversion by the privileged.[ref]Crucially: this happens without malice or even conscious awareness. It’s not that privileged people are evil, in this case, it’s just that goods and services are systematically warped to serve their interests, as social justice activists well understand in other contexts.[/ref] On the other hand, if the dog whistle accusation is only employed when there’s some kind of objective evidence for it, some bigots will get away with dog whistling because there won’t be enough convincing, objective evidence. This is the dog whistle dilemma, and it is intractable.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that our society is fully of intractable problems. The entire criminal justice system is a giant apparatus set up to confront exactly this kind of intractable problem. We balance the principle of presumed innocence and Miranda rights (to protect the innocent) against warrants and imprisonment (to punish the guilty) knowing full well we’re balancing incompatible interests. With fewer legal protections for the accused, we punish more of the guilt, but also more of the innocent. With more legal protections, we protect the innocent but also let the guilt get away. That’s not to say that we’re complacent about the tradeoff, and it’s certainly not to argue that we have the balance correct today. It’s simply to illustrate that the idea of an irreconcilable tradeoff between competing and incompatible values is not new.

The fatal flaw in the contemporary social justice movement is myopia. A criminal justice system that only cared about punishing the guilty would, in short order, discard all civil liberties in the pursuit of that objective, resulting in a nightmare.

No one wants to live in a society where sometimes murderers get away on a technicality. No one wants to live in that kind of society, that is, until we stop to really consider the alternative. A world where courts and prosecutors do not have to abide by the rule of law is even worse.

The same applies here. A world where some people can get away with racism as long as they cloak it in a thin veneer of plausible deniability is not anybody’s idea of a utopia. But a solution like Scalzi’s is even worse, because it’s not only a world riven by polarization and discord, but also a world where social justice itself becomes subjectified and then perverted to serve the interests of entrenched elites.

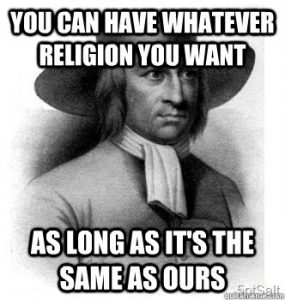

Can the ancient Greeks teach our present-day, anti-trade politicians anything? According to Cornell historian Barry Strauss, they sure can. In a recent article in The Wall Street Journal, Strauss explains that, at first, “Athens’s free-trade zone fostered prosperity, democracy and the soaring confidence that built the Parthenon and fired the Golden Age of Greece. Athens also had a magnetic appeal to immigrants. They came from far and wide and represented rich and poor. Immigrants competed with natives for jobs but not for political power since they were rarely allowed to become citizens.” But the backlash produced three disheartening developments:

Can the ancient Greeks teach our present-day, anti-trade politicians anything? According to Cornell historian Barry Strauss, they sure can. In a recent article in The Wall Street Journal, Strauss explains that, at first, “Athens’s free-trade zone fostered prosperity, democracy and the soaring confidence that built the Parthenon and fired the Golden Age of Greece. Athens also had a magnetic appeal to immigrants. They came from far and wide and represented rich and poor. Immigrants competed with natives for jobs but not for political power since they were rarely allowed to become citizens.” But the backlash produced three disheartening developments: