I just read David Brooks’ most recent column: The Next Culture War. In a nutshell, he argues that Christians ought to abandon their decades-long, fighting retreat against the sexual revolution. “Consider putting aside,” he writes, “the culture war oriented around the sexual revolution.” Channeling Disney’s Frozen, he argues that Christians should just let it go. After all, aren’t there enough other problems to tackle? “We live in a society plagued by formlessness and radical flux, in which bonds, social structures and commitments are strained and frayed,” he writes.

I have a lot of respect for David Brooks. He’s one the people I’d most love to have a lunch conversation with.[ref]Others, if you’re curious, include John McWhorter, Megan McArdle, and Jonathan Haidt.[/ref] But, he doesn’t seem to understand that his suggestion asks for Christians to bail the water out of a sinking boat while ignoring the hole in the hull.

You see, the sexual revolution is the reason that we live in a society that is “plagued by formlessness and radical flux.” In The Social Animal, Brooks argues against the atomization of society on both the left and on the right, with each side focusing myopically on divisible, separable, self-contained individualism. The left argues that human individuals can construct their own gender and sexual identities free from repercussions and it therefore sees free birth control and elective abortion as fundamental rights. The right views collectivism with a hostile gaze, channeling Ayn Rand at times, and argues for personal responsibility sometimes to the point of callousness. These are twin heads of the same coin, and Brooks is right to focus on it. It is one of the defining philosophical tragedies of our age.

But what he seems to fail to grasp is that this radically individualized view of human nature follows in part directly from the sexual revolution. To the extent that the sexual revolution has been about excising sex from the context of marriage and family, it has been an assault on the biological family unit. And this unit–including the bond of husband and wife to each other and also to their children–comprises the two most essential bonds in human society.

To put it simply, social conservatism is animated in no small part by the conviction that biological families are irreplaceable. And so, to the extent that Brooks’ invitation is for social conservatives to give up and try to replace them, he is asking something of us that we simply cannot provide.

As a brief caveat, it’s not entirely clear that that is what he’s asking. He writes that we ought to “help nurture stable families.” I’m just not sure how he imagines this should be accomplished in practice. At one point, he suggests that conservatives abandon the culture wars while at another point he says that “I don’t expect social conservatives to change their positions on sex.” Which is it? Because conservative positions on sex are their participation in the culture wars. It may be the he merely thinks we should keep those beliefs quiet, but again: how does one practically “help nurture stable families” while abandoning resistance to the sexual revolution? Subjective sexual morality, open relationships, sex before marriage, pornography: these are not incidental things that happen to exist alongside “formlessness and radical flux.” These are the acids in which the stable family–as a normative and aspirational social beacon–dissolves.

And this cuts both ways, by the way. To the extent that social conservatives are unwilling to abandon their commitments, their opponents are equally unlikely to let the issue go. Thus, I have to express a deep skepticism of the upside of Brooks’ plan. His idea is that–if we assume for a moment that it is possible to meaningfully nurture families without participating in the culture wars–that suddenly religion will be well-thought of in the world. All of a sudden, we would be known as “the people who converse with us about the transcendent in everyday life.”

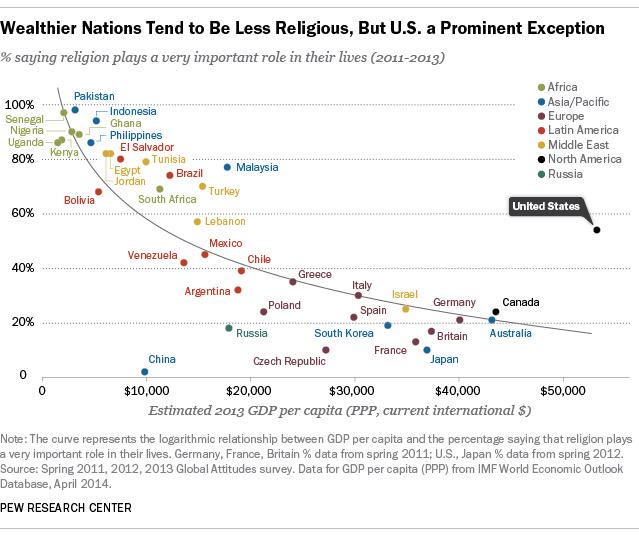

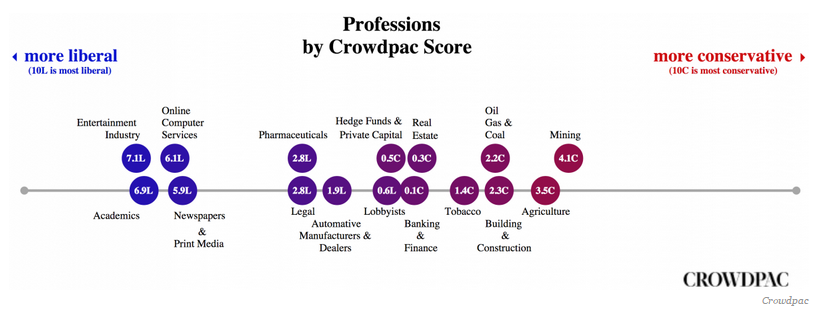

This is impossible, because the commitment social conservatives have to their values is mirrored by the commitment social liberals have to their mutually contradictory values. And as long as social liberals dominate the opinion-making sectors of our society their animosity will continue to be expressed in part by ongoing negative characterization of social conservatives as backwards bigots. And, make no mistake, social liberals do dominate the opinion making sectors of our society: academia, the press, the entertainment industry, and the Internet. Even if social conservatives did go quiet on their beliefs, I have very, very little confidence that our image would suddenly be rehabilitated.

Here is the reality: social conservatives are fighting the sexual revolution–despite it being a losing proposition thus far–because we believe that nothing does more good for children than being raised by their biological parents and that very little does more harm than for little children to be deprived of this natural right.[ref]The extreme cases where one or both of the parents is abusive or neglectful are those exceptional cases.[/ref] This belief necessitates viewing sex as more than merely a recreational activity or even a question of strictly intrapersonal, subjective meaning to be negotiated between the willing adult participants. The belief that immature human beings have a strong moral claim on their parents for protection logically requires a view of sex as a deeply significant act for which consenting adults–male and female together–ought to be morally, socially, and legally responsible.

There is certainly room for compromise and innovation within this conflict. The idea that social conservatives want to wholesale turn back the clock to an imaginary 1950s is an unfair stereotype. Much of the progress–both for women and for minorities–since the 1950s comes to us as precious treasure, dearly purchased and should be treated with humility, gratitude, and respect. Many of the contentious technologies that have fueled this debate–from the pill to IVF–are morally neutral technologies which can certainly coexist with a thoughtful, robust view of normative sexual ethics. There is room for these views to be better articulated within social conservatism, and for some social conservatives to take them more seriously and moderate their positions.

And so I do not want to meet Brooks’ call with a hardline refusal. It’s worth considering. What I wish to convey is that social conservatism is restricted in its freedom to adapt. That is not a design flaw. The point of having principles at all is that–while they may be interpreted or applied in innovative or flexible ways–there is a limit to that flexibility. There are some things that a person cannot do without abandoning principle. For social conservatives, the central principle is the care and protection of society’s most vulnerable, which means our children (before and after birth). An additional article of faith is that no institution can replace the biological family in filling that role. As a result, social conservatives not only will not abandon their opposition to the sexual revolution, they cannot do so and remain social conservatives. Can we do more without abandoning that opposition? I’m sure we can, and I hope we never stop being motivated by that question.

Historian Benjamin Park has an

Historian Benjamin Park has an

A recent blog post at

A recent blog post at