I’ll just start with my thesis: the only rational and consistent outlook of materialist atheism (hereafter referred to simply as atheism for brevity) is that life is pointless. Believing otherwise inevitably involves some degree of delusion or distraction.

I suppose them fightin’ words need support. First, I would point out the following. I will die. You will die. Everyone we know, helped, or hurt will die. Everything we ever accomplished will disappear. The earth will cease to support life. The sun will go supernova. And eventually the ultimate heat death of the universe will occur, beyond which nothing will ever occur again (at least in this universe, but let’s leave out multiverse theory). In that context, how can anything matter?

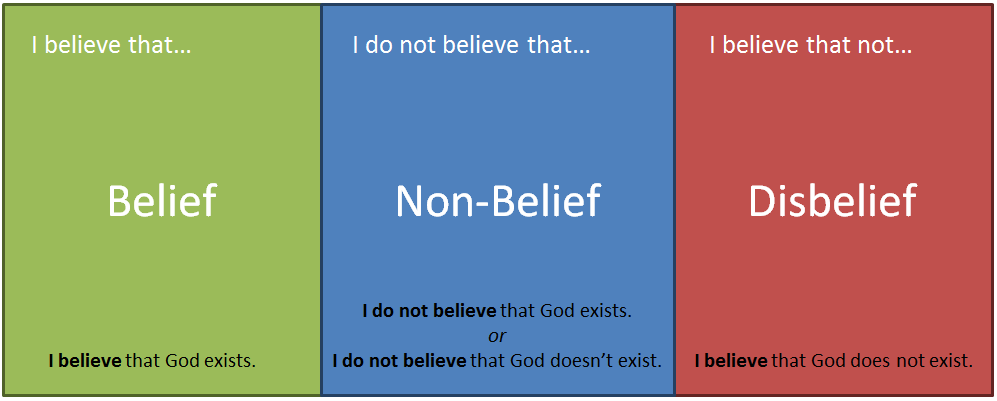

The most common response I hear is that you create your own purpose, sometimes followed by quotes from existentialist philosophers. Within an atheistic point of view, that sounds like the equivalent of saying ‘I will believe in stories that give my life purpose or distract me from my inevitable and permanent non-existence,’ which should appear disturbingly similar to the purpose of religion as understood by many atheists.

Furthermore, saying you create your own purpose seems like saying that Sisyphus would’ve had a purpose if the gods had attached a rolling-counter to his boulder to keep him occupied. SMBC wrote a comic to that effect.

Sisyphus could have attached any personal purpose imaginable to his existence, and we would still say his existence is pointless because it has no final point or purpose. The boulder goes up the hill, and then it goes down, leaving Sisyphus with a net nothing. We expect to meet the same fate under an atheistic point of view. We spend our existence pushing our boulder of accomplishments up the hill of life, and whether in a few decades, a century, or a millennium, that boulder will come right back to where it started. We will be forgotten, and everything and everyone we influenced will cease to exist. We ultimately did it all for no objective purpose.

The next response is usually that my opinion doesn’t really count since I’m not an atheist. I would bring up that I was an atheist, and this question mattered to me, but I think it’s more effective to point that this isn’t my opinion originally. It’s the opinion of many atheist and agnostic thinkers throughout history. For example, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes about Albert Camus that:

Camus sees this question of suicide as a natural response to an underlying premise, namely that life is absurd in a variety of ways. As we have seen, both the presence and absence of life (i.e., death) give rise to the condition: it is absurd to continually seek meaning in life when there is none, and it is absurd to hope for some form of continued existence after death given that the latter results in our extinction.

Leo Tolstoy searched for meaning in life and ultimately found none within a material framework, bringing him to the edge of suicide before his conversion to Christianity. He wrote in his book Confessions:

I sought in all the sciences, but far from finding what I wanted, became convinced that all who like myself had sought in knowledge for the meaning of life had found nothing. And not only had they found nothing, but they had plainly acknowledged that the very thing which made me despair–namely the senselessness of life–is the one indubitable thing man can know.

…

My question–that which at the age of fifty brought me to the verge of suicide–was the simplest of questions, lying in the soul of every man from the foolish child to the wisest elder: it was a question without an answer to which one cannot live, as I had found by experience. It was: “What will come of what I am doing today or shall do tomorrow? What will come of my whole life?”

Differently expressed, the question is: “Why should I live, why wish for anything, or do anything?” It can also be expressed thus: “Is there any meaning in my life that the inevitable death awaiting me does not destroy?”

Somerset Maugham, a famous 20th century writer and agnostic, stated:

If one puts aside the existence of God and the survival after life as too doubtful . . . one has to make up one’s mind as to the use of life. If death ends it all, if I have neither to hope for good nor to fear evil, I must ask myself what I am here for, and how in these circumstances I must conduct myself. Now the answer is plain, but so unpalatable that most will not face it. There is no meaning for life, and life has no meaning.

Personally, my favorite answer comes from Hume. In the face of life’s inevitable end, Hume recommended the very modern solution of distraction:

Where am I, or what? From what causes do I derive my existence, and to what condition shall I return? … I am confounded with all these questions, and begin to fancy myself in the most deplorable condition imaginable, environed with the deepest darkness, and utterly deprived of the use of every member and faculty.

Most fortunately it happens, that since Reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, Nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation, and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends. And when, after three or four hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.

Which I would wager is the most common answer today. I suppose every person feels like they live in an age of unparalleled distraction, but I truly believe that the amount of distraction available to human beings today is greater than almost any period of history. In that context, nobody really needs to bother with whether life has meaning or not.

A brave new world indeed.

Mostly, I write this post as a call for consistency and rationality. I came of age in an atheism that espoused facing the truth, no matter how bleak. Here is the truth. Under an atheistic point of view, life has no objective meaning, so the the options are making up your own (unprovable) story, finding sufficient distraction until you die, or nihilism. Or as my friend Reece succinctly put it:

In my mind, there are really only two kinds of atheists. There is make-believe pretend atheism, and then there is nihilism.

Ultimately, we won’t know until we’re dead who is right. However, we can know in this life who lives consistently with what they believe.