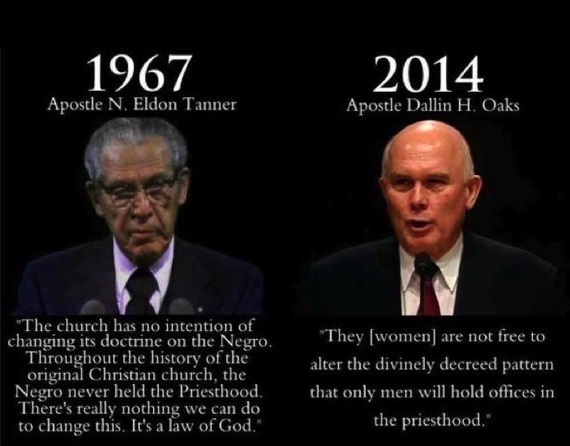

The Atlantic has a recent piece contrasting the claims that to opposition same-sex marriage is just like previous opposition to interracial marriage. This allows those favoring gay marriage to see their cause as similar to that of the Civil Rights Movement, while simultaneously painting their opponents as bigots on par with the Jim Crow South. The author of the piece (who supports equal marriage rights for gays) writes,

Opposition to interracial marriage was all but synonymous with a belief in the superiority of one race and the inferiority of another. (In fact, it was inextricably tied to a singularly insidious ideology of white supremacy and black subjugation that has done more damage to America and its people than anything else, and that ranks among the most obscene crimes in history.) Opposition to gay marriage can be rooted in the insidious belief that gays are inferior, but it’s also commonly rooted in the much-less-problematic belief that marriage is a procreative institution, not one meant to join couples for love and companionship alone. That’s why it’s wrong to stigmatize all opponents of gay marriage as bigots…Opposition to interracial marriage never included a large contingency that was happy to endorse the legality of black men and white women having sex with one another, living together, raising children together, and sharing domestic-partner benefits as long as they didn’t call it a marriage.

The author finds the arguments of same-sex marriage opponents unpersuasive, but not necessarily bigoted (though some certainly are). Of course, the claim that the analogy doesn’t work isn’t new. It just doesn’t show up very often in popular media outlets like The Atlantic. In fact, philosopher Francis Beckwith of Baylor University had an essay a few years ago analyzing the analogy. He found that there was no ban on interracial marriage at common law. This “means that anti-miscegenation laws were not part of the jurisprudence that American law inherited from the English courts. Anti-miscegenation laws were statutory in America (though never in England2), first appearing in Maryland in 1661 after the institution of the enslavement of Africans on American soil. This means that interracial marriage was a common-law liberty that can only be overturned by legislation.” Anti-miscegenation laws were also diverse throughout different regions, ranging from indictments against whites marrying blacks, Mongolians, Malayans, mulatto, and even American Indians. “The overwhelming consensus among scholars,” explains Beckwith, “is that the reason for these laws was to enforce racial purity, an idea that begins its cultural ascendancy with the commencement of race-based slavery of Africans in early 17th-century America and eventually receives the imprimatur of “science” when the eugenics movement comes of age in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” It is often forgotten that Loving vs. Virginia overturned the eugenics-based Racial Integrity Act of 1924. This is why the interracial marriage analogy is so problematic:

For if the purpose of anti-miscegenation laws was racial purity, such a purpose only makes sense if people of different races have the ability by nature to marry each other. And given the fact that such marriages were a common law liberty, the anti-miscegenation laws presuppose this truth. But opponents of same-sex marriage ground their viewpoint in precisely the opposite belief: people of the same gender do not have the ability by nature to marry each other since gender complementarity is a necessary condition for marriage. Supporters of anti-miscegenation laws believed in their cause precisely because they understood that when male and female are joined in matrimony they may beget racially-mixed progeny, and these children, along with their parents, will participate in civil society and influence its cultural trajectory. In other words, the fact that a man and a woman from different races were biologically and metaphysically capable of marrying each other, building families, and living among the general population is precisely why the race purists wanted to forbid such unions by the force of law.

For if the purpose of anti-miscegenation laws was racial purity, such a purpose only makes sense if people of different races have the ability by nature to marry each other. And given the fact that such marriages were a common law liberty, the anti-miscegenation laws presuppose this truth. But opponents of same-sex marriage ground their viewpoint in precisely the opposite belief: people of the same gender do not have the ability by nature to marry each other since gender complementarity is a necessary condition for marriage. Supporters of anti-miscegenation laws believed in their cause precisely because they understood that when male and female are joined in matrimony they may beget racially-mixed progeny, and these children, along with their parents, will participate in civil society and influence its cultural trajectory. In other words, the fact that a man and a woman from different races were biologically and metaphysically capable of marrying each other, building families, and living among the general population is precisely why the race purists wanted to forbid such unions by the force of law.

Beckwith concludes by acknowledging that there are “plenty” of “other arguments for same-sex marriage other than the anti-miscegenation analogy…some of which are serious challenges to the common-law understanding of marriage as requiring gender complementarity.”[ref]One of the best arguments I’ve read in favor of same-sex marriage (which has been highly influential on my own thinking) comes from William & Mary law professor Nate Oman: http://docs.google.com/file/d/0Bxii2wEOc220cDV5SGVQdFlidGc/edit?pli=1[/ref] However, “once one understands the purpose of the anti-miscegenation laws and their relation to the common law understanding of marriage, the analogy not only breaks down, but may actually work against the case for same-sex marriage.”

There are better reasons for supporting same-sex marriage than false analogies. Let’s stick with those, shall we?