Here’s a bit of optimism after the train wreck that was 2016:

By conventional wisdom, 2016 has been a horrible year. Only someone living in a cave could have missed the flood of disheartening headlines. However, if 2016 continues the global trends of previous years, it may turn out to have been one of the best years for humanity as a whole.

Those of us who live in the world of poverty research and rigorous measurement have watched many global indicators improve consistently for the past few decades. Between 1990 and 2013 (the last year for which there is good data), the number of people living in extreme poverty dropped by more than half, from 1.85 billion to 770 million. As the University of Oxford’s Max Roser recently put it, the top headline every day for the past two decades should have been: “Number of people in extreme poverty fell by 130,000 since yesterday.” At the same time, child mortality has dropped by nearly half, while literacy, vaccinations and the number of people living in democracy have all increased.[ref]Similar to last year.[/ref]

The authors point to four things that can make 2017 even better for the poor and destitute:

- “First, give the poor cash. Studies in Kenya and elsewhere show that the simplest way to help is also quite effective. We also know that if we give cash, the poor won’t smoke or drink it away. In fact, a recent look at 19 studies across three continents shows that when the poor are given money, they are less likely to spend it on “temptation goods” such as alcohol and tobacco. More and more research shows that when the poor come into a windfall, they spend it on productive things — sending their children to school, fixing the roof that’s letting in the harsh weather or investing in a business.”[ref]This is perhaps more evidence in favor of a basic income.[/ref]

- “Second, innovative health-care delivery can dramatically improve outcomes…The nongovernmental organizations Living Goods and BRAC Uganda have been training women in Uganda to make a living by going door-to-door selling over-the-counter medications and health products. They function as franchisees in an “Avon lady”-style business. But these small-business owners also perform basic health checks for children to look for symptoms that warrant getting the child to a clinic. One randomized evaluation released this year concluded that taking this health care to people’s homes reduced child mortality (for those younger than 5) by an astounding 27 percent and infant mortality (less than a year old) by 33 percent.”

- “Third, access to mobile money may lift people out of poverty in large numbers…In Kenya, the M-Pesa mobile money system, introduced in 2007, allows anybody with a mobile phone to transfer money through a text message. Research from this year shows that as M-Pesa became more available in a local area, households became less poor — particularly households run by women. The study estimates that 185,000 women changed professions from subsistence agriculture to business and retail and that 194,000 households were lifted out of extreme poverty.”

- “Finally, mobile phone technologies are leapfrogging the reach of traditional telecom infrastructure, and text message reminders are proving to be effective at helping people follow through on things they want to do. One study found that they helped the poor save money. Another in Ghana aimed at combating drug resistance found that such reminders helped people to finish all of their antimalarial drugs. Researchers in Ghana also found that text message quizzes improved girls’ understanding of reproductive health, resulting in fewer reported pregnancies. In Kenya, another interactive text message system offering support for teachers helped reduce student dropouts by 50 percent.”[ref]The importance of mobile phone technologies is underappreciated.[/ref]

2017 is looking up.

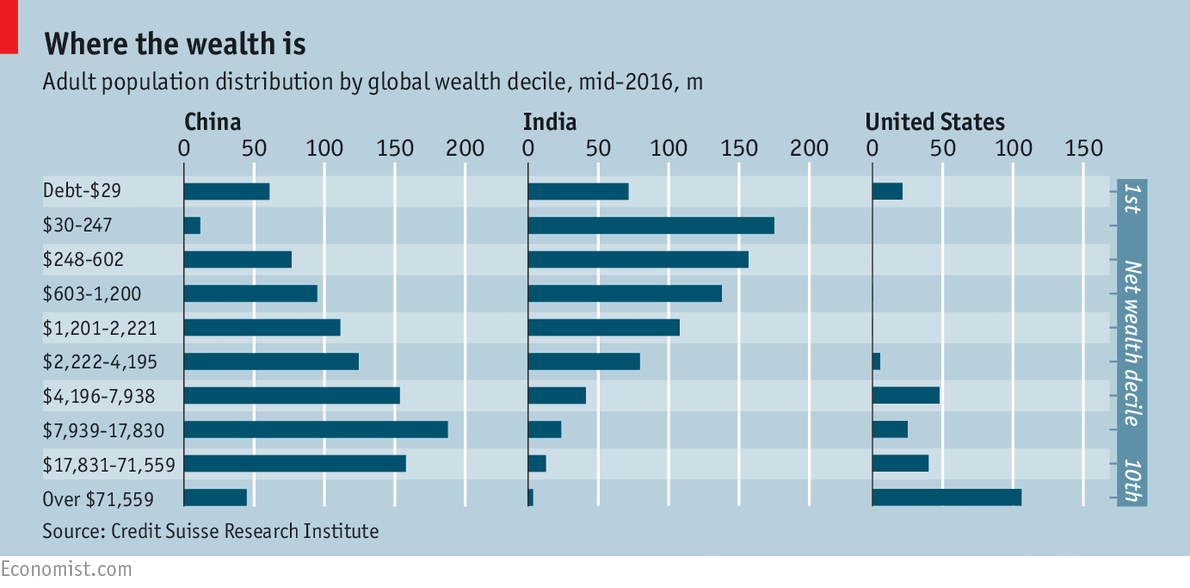

Technically, perhaps, but it’s difficult to feel bad for the top 10-15 percent.

Technically, perhaps, but it’s difficult to feel bad for the top 10-15 percent.

Estimates document that the bombing of South Vietnamese population centres backfired, leading more Vietnamese to participate in Viet Cong (VC) military and political activities and increasing VC attacks on troops and civilians. The initial deterioration in security entered the next quarter’s security score, increasing the probability of future bombing and hence leading to sustained increases in VC activity. Moreover, while US intervention aimed to build a strong state and engaged civic society that would provide a bulwark against communism after US withdrawal, bombing instead reduced the probability that the local government collected taxes, decreased access to primary schools, and reduced participation in civic organisations. To the extent that spillover effects of bombing on other locations exist, the impacts tend to go in the same direction as the effects on the locations that were bombed.

Estimates document that the bombing of South Vietnamese population centres backfired, leading more Vietnamese to participate in Viet Cong (VC) military and political activities and increasing VC attacks on troops and civilians. The initial deterioration in security entered the next quarter’s security score, increasing the probability of future bombing and hence leading to sustained increases in VC activity. Moreover, while US intervention aimed to build a strong state and engaged civic society that would provide a bulwark against communism after US withdrawal, bombing instead reduced the probability that the local government collected taxes, decreased access to primary schools, and reduced participation in civic organisations. To the extent that spillover effects of bombing on other locations exist, the impacts tend to go in the same direction as the effects on the locations that were bombed.

John Horton of New York University

John Horton of New York University

As some of my

As some of my  I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned this before on here, but, as some of you may have guessed, I go to therapy. I haven’t as of late for various reasons, but for a solid two years I went pretty much every other week. My interest in

I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned this before on here, but, as some of you may have guessed, I go to therapy. I haven’t as of late for various reasons, but for a solid two years I went pretty much every other week. My interest in