/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4139120/StateSenateControl-Post-Election-GIF.0.gif)

I’m a little late with this post, since it came out in mid-October, but it’s about some political fundamentals and so it still applies. Besides, if you’re as depressed by Trump’s persistent popularity as I am, you need some good news. Yglesias’ main points in his article for Vox are that:

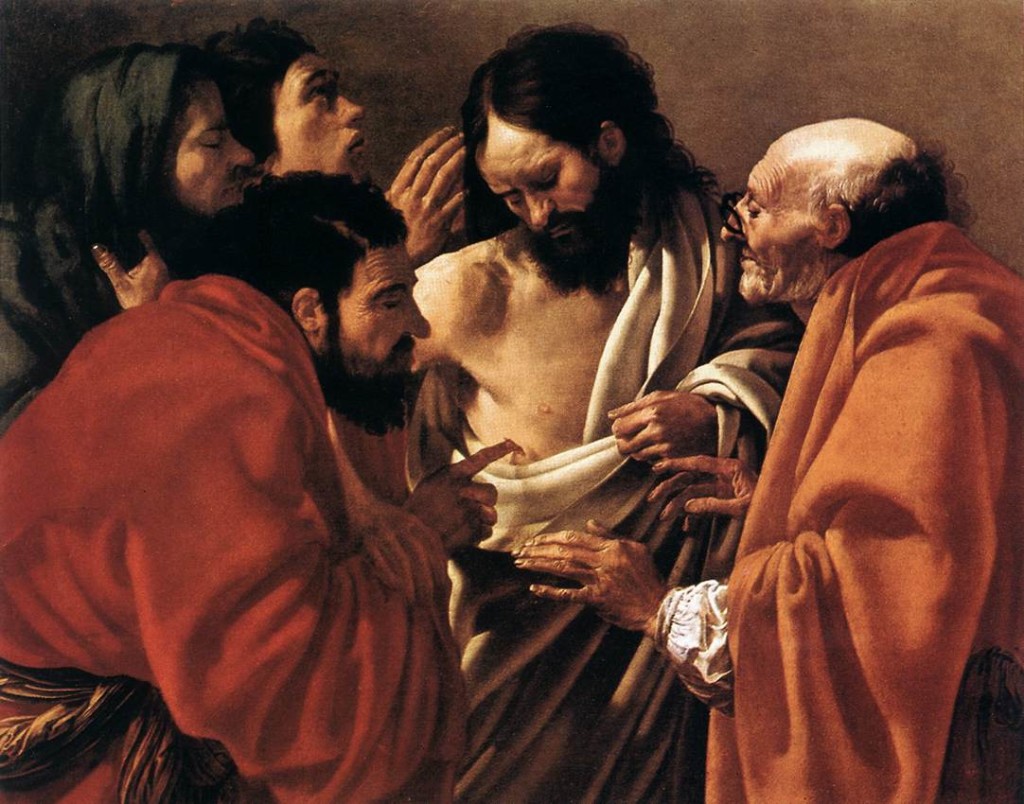

- The GOP has a tremendous amount of political power right now, not only in the House and Senate but especially when you consider state-level positions across the nation.

- A lot of the GOP infighting signals that the GOP actually has power worth fighting over and, more than that, the confidence that it can afford some infighting and still win

- The Democrats have no real plan to regain power, but the GOP has at least two viable options to expand their own power base

This isn’t necessarily a prediction that the GOP is destined for success in the 2016 presidential campaign. The analysis has a lot more to do with the basically every other office in the United State (state and federal) except the White House. I’m not sure that GOP infighting is a clear-eyed as Yglesias seems to think (is there anything clear-eyed about Trump’s candidacy?), but I do think some of his analysis is very interesting, particularly this part:

Essentially every state on the map contains overlapping circles of rich people who don’t want to pay taxes and business owners who don’t want to comply with labor, public health, and environmental regulations. In states like Texas or South Carolina, where this agenda nicely complements a robust social conservatism, the GOP offers that up and wins with it. But in a Maryland or a New Jersey, the party of business manages to throw up candidates who either lack hard-edged socially conservative views or else successfully downplay them as irrelevant in the context of blue-state governance.

Democrats, of course, are conceptually aware of the possibility of nominating unusually conservative candidates to run in unusually conservative states. But there is a fundamental mismatch. No US state is so left-wing as to have created an environment in which business interests are economically or politically irrelevant. Vermont is not North Korea, in other words.

But there are many states in which labor unions are neither large nor powerful and non-labor national progressive donor networks are inherently populated by relatively affluent people who tend to be emotionally driven by progressive commitments on social or environmental issues. This is why an impassioned defense of the legality of late-term abortions could make Wendy Davis a viral sensation, a national media star, and someone capable of activating the kind of donor and volunteer networks needed to mount a statewide campaign. Unfortunately for Democrats, however, this is precisely the wrong issue profile to try to win statewide elections in conservative states.

In other words, the GOP can be competitive basically anywhere at the state level. This is why even several dark-blue states (Maryland, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Illinois) have Democratic state legislatures but Republican governors. (Overall the GOP has 70% of state legislatures and almost 2/3rds of governors are from the GOP.) The GOP does this by abandoning it’s ideological base and just running based on business interests. But the DNC can’t do the opposite. There are several states where their equivalent to business interests (labor unions) are too weak, and so in order to compete at all they have to appeal to their own ideologues.

The one thing Yglesias doesn’t mention is this: if the GOP is actually the pragmatic and ideological flexible party while the DNC is more hobbled by their ideologues, why is the impression in the media basically the exact opposite. Everyone “knows” that the GOP is full of frothing-at-the-mouth crazies while the DNC has an image of balanced rationalism.

And that, I think, is the real problem. The GOP is truly closer to the values of most Americans whereas the DNC is responsive to the interests of an elite class that dominates the national conversation: Hollywood, the mainstream media, and higher education.

Which is also why this piece doesn’t actually instill a bunch of rah-rah partisan enthusiasm in me.[ref]Well, that and the fact that I don’t think of myself as a person with any party loyalty whatsoever. My Republican voting record is entirely a means to an end, and I would switch to Democrat (or anything else) at the drop of a hat if that party or any other better represented my values and had a realistic shot at winning.[/ref] I don’t see the road paved for GOP dominance and–frankly–the idea of the GOP in total charge actually makes me nervous. I mean, we mentioned Trump already, right? Look–assuming we’re talking about someone like Marco Rubio or Jeb Bush–I’ll take a future where the GOP dominates in House, Senate, and White House, but the proposition actually fills me with dread. It’s worth it for the SCOTUS seats, but I’d much rather see both parties competing for American voters across the nation than a conflict based on the GOP’s proficiency at state-level gerrymandering on the one hand and the DNC’s reliance on Hollywood/jouranlism/higher-education acting as unpaid PR flunkies on the other. There are no winners in that scenario.