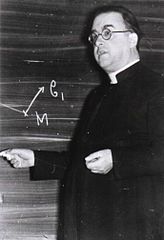

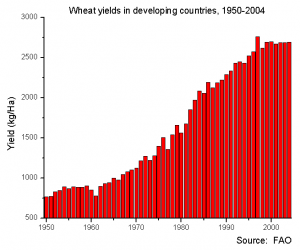

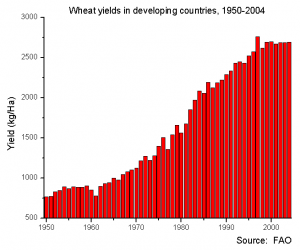

There is a great post over at the Newton Blog on RealClearScience about Nobel laureate Norman Borlaug, the agronomist who was the Father of the Green Revolution. It demonstrates the difference between the Green Revolution and Green Imperialism. Starting in Mexico, he toiled “for endless hours in the lab and in the fields to breed a wheat plant that was resistant to disease, thick-stemmed, and enormously productive.” Mexico’s wheat yield was six times higher in 1963, sixteen years after Borlaug’s arrival. Ninety-five percent of Mexico’s wheat was of “Borlaug’s dwarf variety.” Developing nations began sowing Borlaug’s crop. The results? “Global yields skyrocketed. Starvation rates decreased. Doom was postponed.”

Yet, environmental lobbyists attempted to block Borlaug’s expansion into Africa. They even convinced the World Bank, the Ford Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation to cut funding. While Borlaug was able to boost Ethiopia’s wheat yield to record levels, Africa is still steeped in starvation.

“Some of the environmental lobbyists of the Western nations are the salt of the earth, but many of them are elitists…” he told The Atlantic. “If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for fifty years, they’d be crying out for tractors and fertilizer and irrigation canals and be outraged that fashionable elitists back home were trying to deny them these things.”

But the post doesn’t stop there. It captures perfectly what is often wrong with environmental debates:

As with most debates, this one comes down to intrinsic values. From our lofty position in the developed world, we have the luxury to value the fallacious image of pristine, untouched nature over feeding ourselves. Hunger simply isn’t something that most of us are familiar with.

“These people have never been around hungry people,” Borlaug says of people like this. “They’re Utopians. They sit and philosophize. They don’t live in the real world.”

Proselytizing is easy. But try doing it when you’re starving.