GMU economist Don Boudreaux wrote an open letter to Bloomberg‘s Barry Ritholtz on his blog Cafe Hayek. It was in response to Ritholtz’s recent article on the minimum wage, which claims that “modest increases in minimum wages don’t lead to job losses.” This, in Ritholtz’s view, is “well-established” in the literature. Ritholtz certainly has studies that can backup his position. For example, a brand new study by the Council of Economic Advisers found “that employment in the [generally low-wage] leisure and hospitality industry follows virtually identical trends in states that did and did not raise their minimum wage.” It goes on to note that “[t]his finding is consistent with a well-established empirical literature in which minimum wage increases are often found to have no discernible impact on employment (Card and Krueger 2016, Belman and Wolfson 2014).”[ref]The report has been criticized by some economists, being described as “substantially to the left of where the economics mainstream has been for at least six decades.”[/ref] But Boudreaux points out that the empirical literature does find modest negative impacts on low-wage employment. He writes,

Here’s a list only of some of the more prominent, recent scholarly empirical studies whose authors that find that even modest hikes in minimum wages destroy some jobs:

– Jeffrey Clemens and Michael Wither, “The Minimum Wage and the Great Recession: Evidence of Effects on the Employment and Income Trajectories of Low-Skilled Workers” (2014) (finding that “minimum wage increases reduced the national employment-to-population ratio by 0.7 percentage point”);[ref]The 2016 version can be found here.[/ref]

– Jeffrey Clemens, “The Minimum Wage and the Great Recession: Evidence from the Current Population Survey” (2015) (finding that minimum-wage increases during the Great Recession “reduced employment among individuals ages 16 to 30 with less than a high school education by 5.6 percentage points”);

– Jonathan Meer and Jeremy West, “Effects of the Minimum Wage on Employment Dynamics” (2013) (finding that “the minimum wage reduces job growth over a period of several years. These effects are most pronounced for younger workers and in industries with a higher proportion of low-wage workers”);

– David Neumark, J.M. Ian Salas, and William Wascher, “More on recent evidence on the effects of minimum wages in the United States” (2014) (finding that “the best evidence still points to job loss from minimum wages for very low-skilled workers – in particular, for teens”);

– Yusuf Soner Baskaya and Yona Rubinstein, “Using Federal Minimum Wages to Identify the Impact of Minimum Wages on Employment and Earnings across the U.S. States” (2012) (finding that “[m]inimum wage increases boost teenage wage rates and reduce teenage employment”).

Indeed, you can read a whole book on the matter by David Neumark and William Wascher, Minimum Wages (2008), published by the MIT Press, that concludes that minimum wages do indeed destroy some jobs.

You can dispute the accuracy of all of the above findings, but you cannot dispute that these findings, along with many others that reach similar conclusions, are part of the scholarly record – a record that belies your assertion that it is “well-established” that modest minimum-wage hikes destroy no jobs.

Interestingly enough, Ritholtz cites a University of Washington study on the Seattle minimum wage law and asserts that it “found little or no evidence of job losses[.]” Yet, the study quite clearly states that the minimum wage law led to “a 1.2 percentage point decrease in the employment rate for these low-wage workers. That is, we conclude that Seattle experienced improving employment for low-wage workers, but the minimum wage law somewhat held employment back from what it would have been in the absence of the law” (pg. 12). It later summarizes,

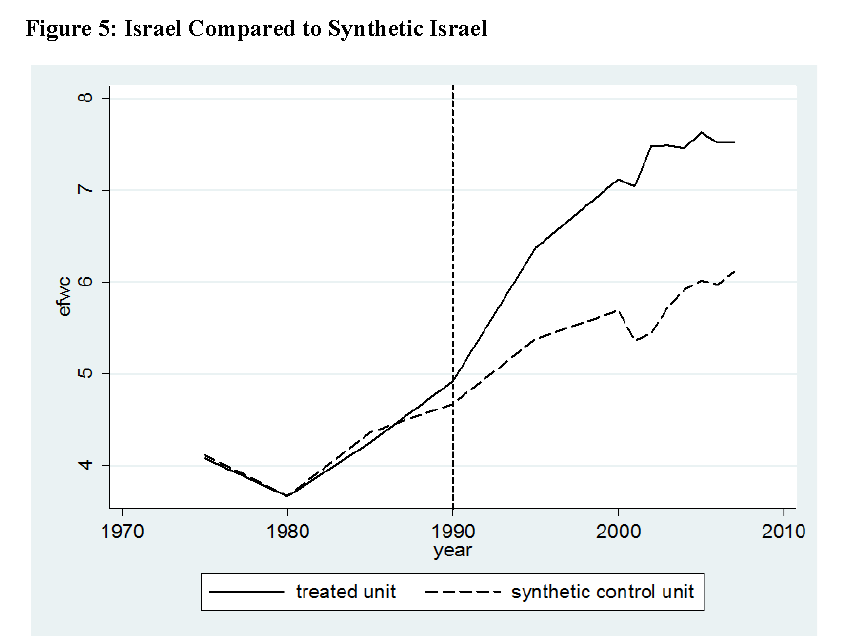

While the intended effect of the Minimum Wage Ordinance (i.e., raising low-wage workers’ wages) appears to have been successful, there appears to have been some negative impacts on these worker’s rates of employment and hours worked. As noted previously, the rate of employment of these workers increased by 2.6 percentage points. However, the comparison regions all experienced even better employment rate increases (3.8% for Synthetic Seattle, 3.9% for Synthetic Seattle Excluding King County, 3.5% for SKP and 2.9% for King County Excluding Seattle and SeaTac). Thus, it appears that the Minimum Wage Ordinance modestly held back Seattle’s employment of low-wage workers relative to the level we could have expected (pg. 22).

What about hours worked?

Hours worked shows a similar pattern. Among workers earning less than $11 per hour at baseline in Seattle, hours worked increased by 12.2 relative to business as usual. So, again, Seattle’s employment situation for low-wage workers improved after the Minimum Wage Ordinance was passed. Hours worked increased, however, by more in the comparison regions (16.4 for Synthetic Seattle, 13.0 for Synthetic Seattle Excluding King County, 21.5 for SKP and 22.5 for King County Excluding Seattle and SeaTac). Thus, on balance, it appears that the Minimum Wage Ordinance modestly lowered hours worked (e.g., 4.1 hours per quarter relative to Synthetic Seattle, or 19 minutes per week) (pg.22).

The study concludes that “[t]he effects of disemployment appear to be roughly offsetting the gain in hourly wage rates, leaving the earnings for the average low-wage worker unchanged.” In short, “for those who kept their job, the Ordinance appears to have improved wages and earnings, but decreased their likelihood of being employed in Seattle relative other parts of the state of Washington” (pg. 33).

I’ve written about the current state of minimum wage research before. I think there are good reasons to be skeptical about its ability to truly help reduce poverty. And as previous research has noted, the debate is more “about the trade-off between good jobs with higher wages and more job stability versus easier access to jobs.”

Let’s try to keep the debate on track.

So write three scholars drawing on their

So write three scholars drawing on their