Despite the misleading title, Tablet has an excellent essay by Shalom Goldman on Muhammad Asad, one of the most important Muslim thinkers of the 20th century. What makes Asad’s story particularly remarkable is that he was born Jewish, in what is now western Ukraine. After converting, Asad gained such proficiency in the Quran and other classical Muslim texts that lifelong Muslims such as the founders of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan sought his advice on how to run a modern state in harmony with religious values. The essay is not a blanket endorsement of Asad (and it only scratches the surface) but if you want to go beyond the headlines when it comes to Islam, sharia, and just politics and religion in general, this is a great place to start.

Philosophy

Pro-Life Atheist at Reason Rally

Life Matters Journal has a new piece by an atheist who attended Reason Rally 2016. It includes her reflections on attending an event where it is assumed everyone is pro-choice because, well, logic, science, and reason. Her main takeaways are that many people don’t know the science, those that do know the science are willing to discriminate, and there is a religious nature to pro-choice adherents. It’s an interesting piece that you can read here. She writes,

Life Matters Journal has a new piece by an atheist who attended Reason Rally 2016. It includes her reflections on attending an event where it is assumed everyone is pro-choice because, well, logic, science, and reason. Her main takeaways are that many people don’t know the science, those that do know the science are willing to discriminate, and there is a religious nature to pro-choice adherents. It’s an interesting piece that you can read here. She writes,

For some reason though many of the same people who claim to trust only hard scientific evidence are willing to deny these basic biological truths in order to continue supporting the violence of abortion.

There is no reason for the secular community to be as pro-choice as they are; in fact as lovers of logic and reason it would only make sense for more atheists to be pro-life. I fear that the reason the pro-choice side is so successful with nonreligious people is partially that pro-lifers have marketed ourselves as a fundamentally religious/Christian movement.

I’ve written about pro-life atheists before. I think, in general, the pro-life movement hasn’t found a way to balance the fact that many pro-lifers are religious, but a lot of the hearts and minds they need to change are not. Thankfully atheist and agnostic voices have been getting stronger in the community, like at Secular Pro-Life. I say thankfully because, even though I am Mormon, I’ve always been more swayed by, or felt more comfortable sharing, logical and scientific arguments. In policy decisions I think those arguments can reach more people. Any movement that has science and ethics on its side should not be afraid to use those benefits.

Healing the Shame That Binds You: PBS Presentation by John Bradshaw

This is part of the DR Book Collection.

As I was writing this post, I learned that author and speaker John Bradshaw passed away just this last month. A bit of personal history: I’ve been going to therapy on and off for the last few years. As I learned more about shame and its debilitating effects, I sought out sources on shame from both my therapist and friends who were also professional therapists. One of these sources was Brené Brown’s work, which I’ve written about here before. But the very first resource given to me was a lecture by John Bradshaw on shame and addiction. Despite his somewhat folksy, almost Southern Baptist-like way of speaking, the ideas he presented were illuminating and paradigm shifting.

As I was writing this post, I learned that author and speaker John Bradshaw passed away just this last month. A bit of personal history: I’ve been going to therapy on and off for the last few years. As I learned more about shame and its debilitating effects, I sought out sources on shame from both my therapist and friends who were also professional therapists. One of these sources was Brené Brown’s work, which I’ve written about here before. But the very first resource given to me was a lecture by John Bradshaw on shame and addiction. Despite his somewhat folksy, almost Southern Baptist-like way of speaking, the ideas he presented were illuminating and paradigm shifting.

I finally got around to finishing his popular book Healing the Shame That Binds You. “As a state of being shame takes over one’s whole identity,” writes Bradshaw. “To have shame as an identity is to believe that one’s being is flawed, that one is defective as a human being. Once shame is transformed into an identity, it becomes toxic and dehumanizing” (pg. xvii). This toxic shame leads to perfectionism, compulsion, addiction, co-dependency, etc. Bradshaw gets into the nitty-gritty, discussing sensitive topics from violence to incest (both emotional and physical). The book is an emotionally difficult, but powerful read.

You can see Bradshaw’s PBS presentation on shame below.

Future Mormon: An Interview with Adam Miller

This is part of the DR Book Collection.

This is part of the DR Book Collection.

Over at Worlds Without End, I’ve written a review of Mormon philosopher Adam Miller’s new book Future Mormon: Essays in Mormon Theology. Those interested in a larger engagement should check it out, but as I describe it there, Miller’s book is an attempt at “a future tense apologetics” that models “a thoughtful and creative engagement with Mormon ideas while sketching, without obligation, possible directions for future thinking” (pg. xii). If future Mormons are anything like what I read here, then they will (compared to my experience with the average present-day Mormon):

- Place grace at the center of the gospel where it belongs.

- Take the materialist metaphysics of Mormonism seriously.

- Be more aware of the implications of their unique and/or innovative doctrines.

- Find the sacred in the mundane and embodied.

- Take a more holistic, almost cosmic view of Mormonism.

- Read the scriptures carefully and recognize the people within them as people, warts and all.

Whether you agree with everything (or anything) in Future Mormon is beside the point. Miller wants you to wrestle with these ideas. The book is meant to start conversations, get the mental wheels turning, and transform the reader into a theologian. In it, he helps lay the foundation for a more thoughtful, earthy, and creative Mormonism; all while extending his hand to readers as an invitation to join him in the process. At least in my case, his hope of inspiring “a thoughtful and creative engagement with Mormon ideas” has not been in vain. And when you pick up Future Mormon and reflect on its pages, I think you’ll find your case to be similar.

You can hear an interview with Adam Miller on Greg Kofford Books’ Authorcast here.

You Are What You Love: A Lecture by James K.A. Smith

This is part of the DR Book Collection.

I already mentioned this book in my last General Conference Odyssey post, so I won’t repeat too much.

In You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit, philosopher James K.A. Smith argues against the modern idea that we are simply “brains on a stick” and that Christian life is achieved by downloading the right spiritual data into our heads. We are not so much thinking creatures as we are lovers, i.e. creatures of desire and habit. He points out the gap between what we think and what we actually want. More disturbingly, he notes that we may not actually love what we think. Our wants are often shaped by what he calls “secular liturgies”: repetitive practices and rituals that orient our desires and shape our habits. Take for example (as Smith does) the mall: the mall doesn’t tell you what to think. It doesn’t hand out a tract with a list of propositions that the mall believes. Instead, it shapes your consumerist desires as it assaults your senses with sights, smells, comforts, etc. This is why Christian liturgy is important and necessary. Christianity is not just a rival worldview, but a rival set of desires. And those desires are shaped through repetition.

In You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit, philosopher James K.A. Smith argues against the modern idea that we are simply “brains on a stick” and that Christian life is achieved by downloading the right spiritual data into our heads. We are not so much thinking creatures as we are lovers, i.e. creatures of desire and habit. He points out the gap between what we think and what we actually want. More disturbingly, he notes that we may not actually love what we think. Our wants are often shaped by what he calls “secular liturgies”: repetitive practices and rituals that orient our desires and shape our habits. Take for example (as Smith does) the mall: the mall doesn’t tell you what to think. It doesn’t hand out a tract with a list of propositions that the mall believes. Instead, it shapes your consumerist desires as it assaults your senses with sights, smells, comforts, etc. This is why Christian liturgy is important and necessary. Christianity is not just a rival worldview, but a rival set of desires. And those desires are shaped through repetition.

You can see Smith lecturing on this idea at Biola University below:

The Bible and the Believer: An Interview with Marc Brettler

This is part of the DR Book Collection.

The Bible can be very problematic for believers, especially those that adopt an early 20th-century fundamentalist reading that transforms it into a history and science textbook. As biblical scholarship has continued to progress, many of the assumptions held by believers have been challenged. Is there a way to read the Bible that includes both scholarship and faith?

The Bible can be very problematic for believers, especially those that adopt an early 20th-century fundamentalist reading that transforms it into a history and science textbook. As biblical scholarship has continued to progress, many of the assumptions held by believers have been challenged. Is there a way to read the Bible that includes both scholarship and faith?

In the Oxford-published The Bible and the Believer: How to Read the Bible Critically and Religiously, biblical scholars Marc Zvi Brettler, Daniel J. Harrington, and Peter Enns explore ways in which historical criticism can be incorporated into various faith traditions, including Jewish (Brettler), Catholic (Harrington), and Protestant (Enns). The book serves not only as good introduction to historical criticism, but a model of how to approach one’s religion “by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118).

You can listen to an interview with Marc Brettler on BYU’s Maxwell Institute Podcast below:

Modesty is more than just clothes

While reading through a Facebook argument on modesty (my time could have been better spent, I know), I realized that for those who hate modesty, their arguments are equivalent to those who hate political correctness (that’s not the right phrase, anymore, right? I can’t keep up.) The argument is pretty much summed up by “What I do isn’t about you and doesn’t affect you, and if it does affect you, fix yourself, not me.” It’s a very come-together, selfless, flower-and-rainbows kind of argument, amirite?

While reading through a Facebook argument on modesty (my time could have been better spent, I know), I realized that for those who hate modesty, their arguments are equivalent to those who hate political correctness (that’s not the right phrase, anymore, right? I can’t keep up.) The argument is pretty much summed up by “What I do isn’t about you and doesn’t affect you, and if it does affect you, fix yourself, not me.” It’s a very come-together, selfless, flower-and-rainbows kind of argument, amirite?

Often I see the same people who argue against modesty also argue for an end to offensive speech, and vice versa. But really both groups of people have picked their preferred form of modesty, will accept no less, and think your form of modesty is oppressive, wrong, and maybe even evil.

The truth is modesty covers both dress and speech because it covers appearance and behavior. And, like it or not, modesty is intertwined with respect. Because what we do and say affects who we are and also affects the way people perceive us. (Clearly our dress is only a small part of what we do.) We aren’t just inanimate blobs floating around that no one can see or hear (and therefore never be offended by us). To say our speech or our dress doesn’t matter because “I’ll do what I want” is not going to engender a polite society.

This is not to say you should be assaulted for what you wear! (I know this is a particular pet peeve of the anti-modesty crowd.) And, similarly, you should not be assaulted for what you say. [ref]I’m pretty sure assault does not fall under the umbrella of modesty.[/ref] But respect goes both ways, and certain places and people require an amount of appropriateness in both dress and speech. [ref]I love my friends “do not use your underwear as an accessory” version of modesty. I haven’t come across a good, simple saying for speech yet.[/ref] I think you should be modest for nice people not for the scum of society.

I also don’t think we should spend much time policing one another (this is my hope that the internet shuts up, I know, very likely). There are always lines to be drawn. But if you really cling to wear whatever you want/say whatever you want or cover every inch/zip your lip, you’re probably being too inflexible and should chill a bit.  Nicely dressed meteorologists don’t need to put a sweater on, but we don’t need to see celebrities naked (or even nearly-naked) selfies (sorry, no link). College graduates don’t need protection from Secretaries of States from politically different administrations, but women should not be harassed online for doing their jobs.

Nicely dressed meteorologists don’t need to put a sweater on, but we don’t need to see celebrities naked (or even nearly-naked) selfies (sorry, no link). College graduates don’t need protection from Secretaries of States from politically different administrations, but women should not be harassed online for doing their jobs.

Overall, if you spend any time on the internet, you should realize that many aspects of our society could benefit from a little modesty. But that doesn’t mean we all need to become Puritans.

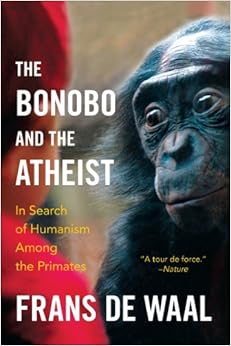

The Bonobo and the Atheist: An Interview with Frans de Waal

This is part of the DR Book Collection.

I was at the zoo recently with my wife, my sister-in-law, her husband, and their baby. As we looked at the bonobos and observed their eerily human behavior, I made the comment that I needed to read primatologist Frans de Waal’s book The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates. Morality, de Waal argues, is bottom-up. Behaviors we label as “moral”–such as empathy or fairness–are grounded in our evolutionary development. Morality arises from the emotions and social rules that can be found in other primates. The book made Nathaniel’s best of 2015 list. And I happen to agree with one of his criticisms:

I was at the zoo recently with my wife, my sister-in-law, her husband, and their baby. As we looked at the bonobos and observed their eerily human behavior, I made the comment that I needed to read primatologist Frans de Waal’s book The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates. Morality, de Waal argues, is bottom-up. Behaviors we label as “moral”–such as empathy or fairness–are grounded in our evolutionary development. Morality arises from the emotions and social rules that can be found in other primates. The book made Nathaniel’s best of 2015 list. And I happen to agree with one of his criticisms:

Merely because you can show how a thing arises through evolution doesn’t get you out of this problem. You could explain how humans came to have the ability to reason objectively, but that wouldn’t mean that logic and math were suddenly subjective. It would just prove that somehow evolution managed to get us in touch with non-contingent, objective reason. Same idea here: you can explain how humans came to behave morally or even to understand and think about morality, but it’s a colossal mistake to think that, in so doing, you have proved that morality is “constructed” or in any way subjective any more than reason or logic are. (For fun: let someone try to reason you out of the position that reason is objective. See how that works? It’s a non-starter.)

Even if the philosophy is lacking, the science is fascinating. You can see a Big Think interview with de Waal below.

I Dissent

I just finished listening to a bunch of science fiction stories in rapid succession so that I could cast informed votes for the annual Hugo awards and post the reviews to my new blog.[ref]The Loose Canon is where I will do most of my future blogging about science fiction.[/ref] That done, I returned to some of the non-fiction audiobooks I’ve been waiting to get into, especially Redefining Reality: The Intellectual Implications of Modern Science. It’s been a fantastic spring day, and there was an exquisite, gentle evening breeze as I walked the dog. Meanwhile, Professor Steven Gimbel explained the impact of World War II on the field of social psychology:

In the first half of the 20th century, psychology had the luxury of debating whether a subconscious mind existed and whether scientific methodology required limiting the field of study to stimulus and response, but after the horrors of World War II, psychology changed… The specter of the Holocaust raised deep and troubling question about the human mind and its relation to authority… The reaction to Nazi atrocities in the scientific world is shaped by what are perhaps the three most famous psychological experiments: Stanley Milgram’s obedience study, Solomon Asch’s group think study, and Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford prison study. [ref]The quote is my own transcription, and I added the hyperlinks.[/ref]

I think Millgram’s and Zimbardo’s experiments are the most famous. At least, those are the ones that I’ve read about and seen the most. I was familiar with Asch’s study as well, but I haven’t seen it come up as often, and I was unprepared for how deeply a simple remark made by Gimbel would strike me. It hit so forcefully that I hit pause on the audiobook (to keep that thought forefront on my mind), came home, opened my laptop, and began this blog post.

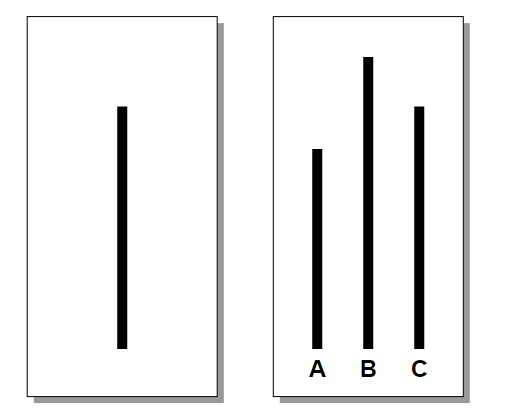

In Asch’s study, participants were given a simple task. They had a reference image that showed a vertical line, and then another image that showed three vertical lines. One of the three matched the vertical line in the reference image, and all they had to do was pick out the correct match. They were asked to do this 18 times. The trick is that the participants were seated at a table with seven other people who were secretly in on the experiment. On the first two rounds, these seven individuals all gave the same answer, and it was the correct one. But on the third trial, these individuals all gave the same incorrect answer. Over the course of the next 15 trials, the seven plants gave the wrong answer 11 times, and in each case all seven of them gave the same incorrect answer.

So you’ve got eight people seated around a table answering a perfectly obvious question. Seven of them have just given the identical, incorrect answer. The point of the experiment was to find out what the eighth person–the only real subject of the study–would do. Given that this is considered one of the “three most famous psychological experiments” you can guess how it turned out even if you don’t already know: 75% of subjects went with the group consensus (even though it was obviously wrong) at least one out of the 12 times when the seven fake participants picked the wrong answer.

There are all kinds of interesting details to the study, especially when it comes to the rationales that the participants gave afterwards to explain why they had refused to go along with the group or why they had, at least some of the time, opted to go along with the group despite what was clearly true. But here’s what Gimbel said about the study that so arrested me:

Asch expanded the study to see what would happen. He showed that the bigger the majority, the stronger the pull to conform, but that if even one person dissented before the test subject, that the test subject was then more likely to voice his different view. Asch showed empirically that having someone else agree with you is a powerful tool in making people willing to take a contrary position. But, if that person [the test subject] were deserted by his fellow dissenter, conformity followed rapidly.[ref]I transcribed this quote from the audio and then added emphasis to the text version.[/ref]

Now, before I continue, I want to take a moment to explain that–contrary to popular opinion–I’m not interested in attacking conformity. Conformity gets a bad rap in movies like Dead Poet Society.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAyr0kWRGE

The sentiment in that clip is hogswash. Unfortunately, so is most anti-non-conformity sentiment. There’s an entire guide to being a non-conformist, but–like all such ironic anti-non-conformity statements–the actual point is that non-conformity is bad because it’s a kind of conformity.

So, even the anti-non-conformists are trapped in an non-conformity mindset. Conformity can’t catch a break. Which is a shame, because conformity is actually pretty important in helping to form human society and–because we are social animals–to form who we are as well.

In The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt introduces this concept in a chapter called “The Hive Switch.” He starts with an example of exactly the kind of military drill (e.g. marching) that Dead Poet Society maligns, citing Wiliam McNeill (a World War II veteran) describing drill this way:

Words are inadequate to describe the emotion aroused by the prolonged movement in unison that drilling involved. A sense of pervasive well-being is what I recall; more specifically, a strange sense of personal enlargement; a sort of swelling out, becoming bigger than life, thanks to participation in collective ritual.[ref]The Righteous Mind, page 221[/ref]

After his service, McNeill studied this kind of conformity (which he called “muscular bonding”) and found that it “enabled people to forget themselves, trust each other, function as a unit.”[ref]The Righteous Mind, page 222[/ref] What works like Dead Poet Society miss[ref]And it is far from alone in this regard.[/ref] is that conformity is a path to collective consciousness. In the same chapter that begins with marches and drills, Jonathan Haidt goes on to discuss ecstatic mass dancing, awe in the presence of nature, hallucinogens, and raves. One of the roles of conformity, in other words, is to enable humans to access a “hive switch” that flips our identity from individualist to collective. The term “collective” often has negative connotations (like conformity itself), until one realizes that it also implies (as McNeill points out) selflessness and trust.

Writing in The Origins of Virtue, Matt Ridley emphasizes a similar point. One of the grand puzzles of human nature is that–alone of all animals in existence–we have the capability to come together in large groups to work for collective goals without close genetic ties.[ref]Ant colonies and bee hives work together, but they are also all (effectively) siblings, and so there is no mystery here, genetically speaking.[/ref] In his book, he surveys a lot of literature on evolutionary psychology and game theory trying to explain why it is that human beings, in practice, are able to escape the prisoner’s dilemma. The prisoner’s dilemma is the most famous game theory scenario, and it proves that–if humans were strictly self-interested and rational–we would effectively never cooperate in large groups. And yet, we do cooperate in large groups. Is there any theoretically explanation for this? Yes, it turns out, there is. The only kind of society in which cooperative strategies can survive without being overwhelmed by cheating free-loaders is a conformist society.

There is one kind of cultural learning that makes cooperation more likely: conformism. If children learn not from their parents or by trial and error, but by copping whatever is the commonest tradition or fashion among adult role models, and if adults follow whatever happens to be the commonest pattern of behavior in the society—if in short we are cultural sheep–then cooperation can persist in very large groups.[ref]The Origins of Virtue, page 181[/ref]

So, instead of just making fun of non-conformists for also being conformists, it’s worth keeping in mind that conformity is a route to selflessness and, perhaps, the key to humanity’s unique ability to successfully cooperate in large, unrelated groups. But, if that’s not enough, keep in mind that things like language itself only work because of conformity. If we all tried to be non-conformists in our language, then communication would be literally impossible.

This was a long digression, but it’s something I’ve been meaning to get around to for a while anyway. To get things back on track: I don’t think non-conformity is a laudable goal in itself, but I do think that diversity matters a lot. I worry about echo chambers and I worry about group think and I worry about bubbles. And I worry about that eighth person, sitting at the table, staring at the line, wondering what on Earth could be happening that everyone else is reporting a reality that is the opposite to what he feels. I’m not really worried about whether or not this person gives the correct answer (more on that at the end), but I am very worried that this person feel empowered to give their honest answer.

This is what I had in mind when I recently read an older Slate Star Codex piece: All Debates Are Bravery Debates. In the piece, Scott Alexander argues for being charitable about extreme positions as follows:

Suppose there are two sides to an issue. Be more or less selfish…

There are some people who need to hear both sides of the issue. Some people really need to hear the advice “It’s okay to be selfish sometimes!” Other people really need to hear the advice “You are being way too selfish and it’s not okay.”

It’s really hard to target advice at exactly the people who need it. You can’t go around giving everyone surveys to see how selfish they are, and give half of them Atlas Shrugged and half of them the collected works of Peter Singer. You can’t even write really complicated books on how to tell whether you need more or less selfishness in your life – they’re not going to be as buyable, as readable, or as memorable as Atlas Shrugged. To a first approximation, all you can do is saturate society with pro-selfishness or anti-selfishness messages, and realize you’ll be hurting a select few people while helping the majority.

In terms of explanation, Scott Alexander is right on the money. He says, for example:

This happens a lot among, once again, atheists. One guy is like “WE NEED TO DESTROY RELIGION IT CORRUPTS EVERYTHING IT TOUCHES ANYONE WHO MAKES ANY COMPROMISES WITH IT IS A TRAITOR KILL KILL KILL.” And the other guy is like “Hello? Religion may not be literally true, but it usually just makes people feel more comfortable and inspires them to do nice things and we don’t want to look like huge jerks here.” Usually the first guy was raised Jehovah’s Witness and the second guy was raised Moralistic Therapeutic Deist.

That sounds familiar, and I think we all have friends who used to be really extreme in one direction, and now they’ve gone overboard in the other extreme.[ref]In The Bonobo and the Atheist, Frans de Waal pokes fun at New Atheists in general and Christopher Hitchens in particular: “Some people crave dogma, yet have trouble deciding on its contents. They become serial dogmatists.” (page 89)[/ref] Where I disagree with Scott Alexander, however, is in accepting that this kind of overreaction is basically acceptable. In my experience, both Ayn Rand (who says greed is good) and Peter Singer (who argued against any special concern for family members[ref]Frans de Waal, also in The Bonobo and the Atheist, points out that when Singer’s mother actually did become gravely ill he used his money to hire private care for her in direct contradiction of his own dogmatic utilitarian ideology. Singer said “perhaps it is more difficult than I thought before, because it’s different when it’s your mother.” De Waal commented: “The world’s best-known utilitarian thus let personal loyalty trump aggregate well-being, which in my book was the right thing to do.” (page 184-185)[/ref]) are just plain bad. I don’t care how selfish you are, Peter Singer is still overkill. I don’t care how selfless[ref]In a pathological sense.[/ref] you are, Ayn Rand is still crazy.

So this is the world I find myself in. When I look around, I feel like the eighth guy at the table on several issues. To pick just one that we talk about a lot here at Difficult Run, go with minimum wage. I’m looking at the discussions around me,[ref]I don’t mean our commenters here at Difficult Run. I think you guys are pretty great. I mean the debates as I see them unfolding on my Facebook feed, etc.[/ref] and I just can’t really believe what I’m hearing.

But when I look around for people who will stand up with me and dissent, what I see is a lot of what Scott Alexander is describing. Take “socialism.” The term, in almost all debates you will see today, has no solid meaning. It’s just a flag. And on one side you’ll see these “taxation is theft” ultra-libertarians charging against the flag of socialism and on the other side you’ll see all these people who seem to have forgotten the second half of the twentieth century rallying around the flag of socialism. Maybe some of the “taxation is theft” folks escaped Soviet oppression (as Ayn Rand did, not by coincidence) and a lot of the “Mao? Stalin? Who were they?” socialists do come from elite backgrounds in the world’s leading capitalist economy, so “to a first approximation” their points are valid. That doesn’t mean they are actually helping matters when they add their extreme, absolutist viewpoints to the discussion. Technically, the “taxation is theft” guys are going to side with me to oppose minimum wage hikes, but I really wish they wouldn’t.

Too often it seems like your choices are either (1) conform to the political fad of the day or (2) engage in extreme, overreactions. Pick your poison.

But I don’t want to pick my poison.

I don’t, for example, want to have to pick and choose between conformity and diversity. I value both. Conformity is essential for language, is vital for social cohesion, and is–in short–the glue that holds the fabric of our society together. Anyone who says they are a nonconformist is lying or a sociopath, just like anyone who says that they don’t care what other people think about them is lying or a sociopath. Everyone is a social animal, everyone cares what (some) other people think, and everyone conforms (to some group). But if you overemphasize conformity, then you get group-think. You stifle creativity, restrict free inquiry, stifle scientific curiosity, and hamstring debate and compromise. We need diversity, too. We need both.

Here’s the reason I wrote this post. Here’s the thing that Gimbel said, about the Asch experiments, that really stood out. What did it take to empower that eighth person to answer honestly? They didn’t need anything extreme. They didn’t need any theatrics. They didn’t need Ayn Rand and they didn’t need Peter Singer. All it took was one person just calmly, quietly validating what they saw.

In Asch’s experiment, the truth was obvious. In the real world, on most issues where there is a lot of debate, the truth isn’t obvious. What’s more, I’m going to be publishing a post (hopefully soon) called “Nobody Gets It All Right” that will say just that: based on my understanding of history and various biographies, everybody is wrong about most of what they believe. And I take that to heart. I have a lot of opinions. Most of them are probably wrong, at least in the sens that–two decades or two centuries from now–the things I think are true will be either discredited or (more likely) irrelevant.[ref]Don’t get too excited. The same is true for you, too.[/ref]

So I do want to dissent. I do want to raise my voice–calmly, politely, modestly–and say that the emperor’s got no clothes on when it appears to me that the emperor, in fact, does not have clothes on. But the basis of my dissent is not “I am confident that I am right.” At this point in my life, that conviction alone is not enough to stir me to publish a post. Instead, my motivation is something like, “I am dedicated to living in the kind of world where people speak their minds honestly.” Because, if I have to pick just a few areas where I want to place a very high degree of confidence–like only two or three–that’s going to be one of them.

There’s a bit of conventional wisdom about Internet debating. The point of the debate is never to persuade the other guy. The debate is always for the sake of the audience. There’s truth to that, but it can be taken too far, and made into a philosophy where arguing online is a gladiatorial spectator sport with both sides essentially playing to their respective fan bases with no interest in sincere, honest interaction with each other’s points. That’s not what I want to do.

Instead, I just want to be the one guy at the table who says, “I see things differently” that thereby enables the eighth guy to have an easier time in saying the same thing.

That, in a nutshell, is one of the fundamental reasons Difficult Run exists.

Eternal Progression?

Many Mormons live with the hope that their families will be together forever – such hopes are inscribed upon us in primary. We hope to live righteously and faithfully so that we can all make it to the celestial kingdom together. Many, at one point or another, experience the fear that a family member might go astray and forsake the straight and narrow, disqualifying themselves from the celestial kingdom.

What are we supposed to do, how should we react? We endeavor to be all the more devout in regards to our religious practices in hopes that our goodness can somehow affect those we love. Religion, which we had hoped would be the anchor of our family ends up sinking it in storm tossed seas. The bonds in which we had put so much faith have fractured. The grief and pain many feel is beyond comprehension as they try to understand what the consequences will be – will mothers and fathers be forever separated from their children, children their parents, siblings divided from siblings by great gates?

Many have dreamed of the possibility to progress from one kingdom to the next – that if we were not perhaps ready to receive all that we could have received by the end of this life, that we might still have the opportunity to become ready in the hereafter. There are also many who reject the idea out of hand and say it is a heresy and an abomination – though not all who reject this notion do it out of anger. However, it is often the voice which is fueled by outrage and indignation is louder than the voice of quiet hope. Where does this indignation come from?

In Luke chapter 15 we read the story of two brothers and their father. The elder brother in this story becomes angry and bitter when his brother, returning from a riotous (“sinful”) life, is greeted with celebration and festivities.

“And he was angry, and would not go in: therefore came his father out, and entreated him. And he answering said to his father, Lo, these many years do I serve thee, neither transgressed I at any time thy commandment… But as soon as this thy son was come, which hath devoured thy living with harlots, thou hast killed for him the fatted calf. And he said unto him, Son, thou art ever with me, and all that I have is thine.”

The elder brother isn’t as much upset that the prodigal son has come home as he is that he has lived a life of obedience and seems to profit no more from it than his brother who has lived a life of sin. However, what the elder brother does not seem to realize is the pain and suffering which his younger brother, the prodigal son, endured as he gathered experiences from the life style which he had chosen. The older brother was never driven to the point of starvation where he would look on with envy as pigs were given more to eat than he, but rather was constantly a participant in the bounty and love of his father. The older brother did not recognize that suffering is sin’s constant companion however well it may conceal itself; we must not heap more punishment upon those who have already endured pain we know not of. We must ask ourselves who are we most akin to in this story; the younger brother, the elder, or the father? Why do we choose to live the life we do? Is religion a tool to grant us our treasures in heaven or is religion a tool to teach us to have heavenly desires? Do we see righteousness as a way to secure greater accolades or do we hope to weave acts of habitual goodness into our moral tapestry?

Another parable found in Matthew 15 highlights this principle:

So when even was come, the lord of the vineyard saith unto his steward, Call the labourers, and give them their hire, beginning from the last unto the first. And when they came that were hired about the eleventh hour, they received every man a penny. But when the first came, they supposed that they should have received more; and they likewise received every man a penny. And when they had received it, they murmured against the goodman of the house.” The master of the vineyard then responds, “Is it not lawful for me to do what I will with mine own? Is thine eye evil, because I am good?”

The laborers of the Vineyard who had been working all day did not expect more because they thought they deserved more money for their work, but because they believed they deserved more than those who had worked less. They believed themselves to have become more worthy through their works that they might be recipients of the Master’s mercy. They had become so fixated and concerned with their own standing and desires for mercy that they had forgotten how to sympathize and be joyous for others who were also in need of the Master’s mercy – a position that they themselves were in not so long ago. How quick we are to become the servant who was forgiven much but forgave little (Matthew 18:21-35). The question then isn’t if we are able to receive God’s mercy, but if we are changed by His mercy – do we desire an even more abundant out-pouring of mercy for our enemies (for if ye love them which love you, what thank have ye?).

Which of us, when partaking of the sacrament, is truly worthy of that broken body which we remember and that sacred blood which for us was spilt. It isn’t solely the act of taking sacrament which cleanses us, but the desire to partake of the sacrament. Worthiness isn’t a status to achieve or an object to obtain, but rather it is found within the desires of our hearts and soul. Worthiness is found in the desire to repent and to become something heavenly. And though it is said that faith without works is dead, works without faith is equally dead.

C.S Lewis asks a question in his book, The Great Divorce, “Is Judgment not final? Is there really a way out of hell into Heaven? There have been many who have spoken with conviction that there is indeed hope of eternal progression which is only halted by our own desires. J Reuben Clark once said,

“I am not a strict constructionalist, believing that we seal our eternal progress by what we do here. It is my belief that God will save all of His children that he can: and while, if we live unrighteously here, we shall not go to the other side in the same status, so to speak, as those who lived righteously; nevertheless, the unrighteous will have their chance, and in the eons of the eternities that are to follow, they, too, may climb to the destinies to which they who are righteous and serve God, have climbed to those eternities that are to come.” (J. Reuben Clark, Church News, 23 April 1960, p. 3)

President Clark believed that within the eternities and eons of time, progression and change are possible. Joseph Smith believed that a spirit in the lowest kingdom “constantly progresses in spiritual knowledge until safely landed in the Celestial”1 and Brigham Young believed that those who don’t inherit the Celestial Kingdom “would eventually have the privilege of proving themselves worthy and advancing to a celestial kingdom but it would be a slow process”.2

I believe that just as agency is eternal, so is progression; that progression only ceases when desires to progress cease. As long as there is more knowledge to be obtained then possibility to change exists – and that is only made possible through the atonement. President Packer once commented, “I repeat, save for the exception of the very few who defect to perdition, there is no habit, no addiction, no rebellion, no transgression, no apostasy, no crime exempted from the promise of complete forgiveness. That is the promise of the atonement of Christ.” 3

“There are only two kinds of people in the end” says Lewis, “those who say to God, ‘Thy will be done,’ and those to whom God says, in the end, ‘Thy will be done.’” 4 God will not force any in to heaven, that choice is ours. And it isn’t simply a choice of relocation, but a choice of repentance and becoming. As Mormon clearly says in chapter 13, “Do ye suppose that ye could be happy to dwell with that holy Being, when your souls are racked with a consciousness of guilt[?]” This life and this moment now is the best time to truly become disciples of Christ and to weave patterns of righteousness into our own very being. It is here, in the space of faith and doubt allowed to us by the suspension of knowledge through the veil that we are truly able to choose that which we desire to believe and desire to become. God has allowed us the freedom of choice not to test what we will do, but to allow us the freedom to act and believe according to our own beliefs and to learn where those beliefs lead.

———————————————————————————————————–

In case there are questions about the post regarding Elder Bruce R. McConkie’s well known address, I give the following thoughts.

Foremost it is important to recognize this following tidbit of information, “President Kimball was not doctrinaire, and he felt a need to intervene in doctrinal matters only when he saw strong statements of personal opinion as being divisive. Elder McConkie’s talk at BYU on “The Seven Deadly Heresies” implied he had the authority to define heresy. Among other things, he denounces as heretical… the idea of progression from kingdom to kingdom in the afterlife… President Kimball responded to the uproar by calling Elder McConkie in to discuss the talk. As a consequence, Elder McConkie revised the talk for publication so as to clarify that he was stating personal views”. Among with a few other changes, McConkie added to the end of his talk, “every person must choose for himself what he will believe.” [5]

I don’t claim to know McConkie’s thoughts or reasoning behind his conviction of this thought being a heresy – but I’ve come to reconcile his words with another truth. Believing that there is progression in the eternities to come could dissuade many from seeking to emulate the character of Christ in this life. However, if this thought were to be a truth and it served to dissuade us from choosing a life in pursuit of emulating Christ, then our spiritual maturity is much like the elder brother of the prodigal son. If only the fear of not being able to progress in the future and only being able to progress now is what roots us in the Gospel and teachings of Christ, then we have missed the meaning of those teachings entirely. The Gospel isn’t given to us to save us from future pain and misery (though that is a byproduct) but to help us choose now, this day, to become more like our heavenly parents and to know how we can work on accomplishing that goal. Importantly, the gospel isn’t there to incentivize us to do good out of the fear of being damned or for the sake of more blessings, but out of love and devotion – charity is the center of Christ’s teachings.

Sources

- (Franklin D. Richards, “Words of the Prophets,” CHL.; Charlotte Haven, 26 March 1843, “A Girl’s Letters from Nauvoo,” The Overland Monthly96 (Decemeber 1890): 626 http://www.olivercowdery.com/smithhome/1880s-1890s/havn1890.htm credit for Michael Reed).

- Brigham Young, in Wilford Woodruff Journal, 5 aug 1855

- “The Brilliant Morning of Forgiveness,” Ensign, November 1995

- The Great Divorce

- Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 101