No one. Stop it. No seriously, stop.

The story of this thought starts here. Dan Kahan over at the Cultural Cognition blog found in his studies that, counter to his expectations, “identifying with the Tea Party correlates positively (r = 0.05,p = 0.05) with scores on the science comprehension measure.” Aha, take that Democrats! Except Kahan very clearly states “the relationship is trivially small, and can’t possibly be contributing in any way to the ferocious conflicts over decision-relevant science that we are experiencing.” So what does the Tea Party do? Runs with it anyways like the Democrats have done before.

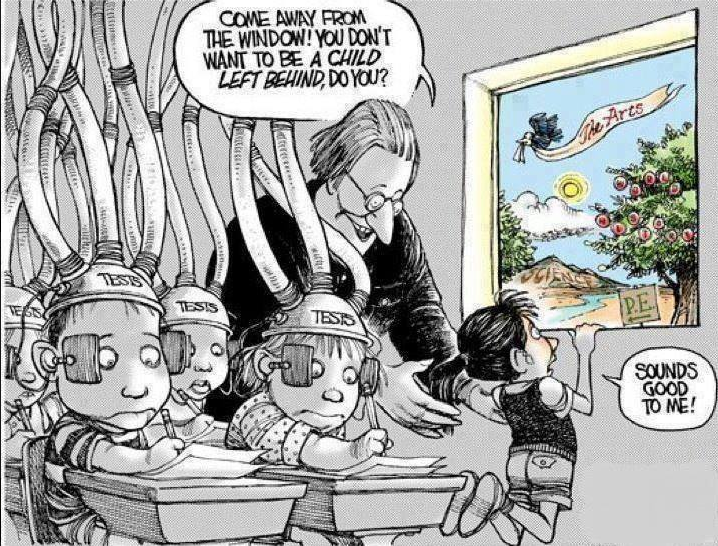

This is dumb and has to stop. Using statistics with zero understanding of both the particular study and statistics in general is going to show exactly one thing: your preexisting biases. But more importantly, this arguing back and forth about whose group is “better” at science or whose group “accepts” more science is often nothing more than an attempt to be “good” at science by osmosis. If my group is better at science, that must mean that I personally am better at science, right? Or if I accept more scientific conclusions, that must mean I am better at science? No, and no. For example:

…there is zero correlation between saying one “believes” in evolution & understanding the rudiments of modern evolutionary science.

Those who say they do “believe” are no more likely to be able to be able to give a high-school-exam passing account of natural selection, genetic variance, and random mutation — the basic elements of the modern synthesis — than than those who say they “don’t” believe.

In fact, neither is very likely to be able to, which means that those who “believe” in evolution are professing their assent to something they don’t understand.

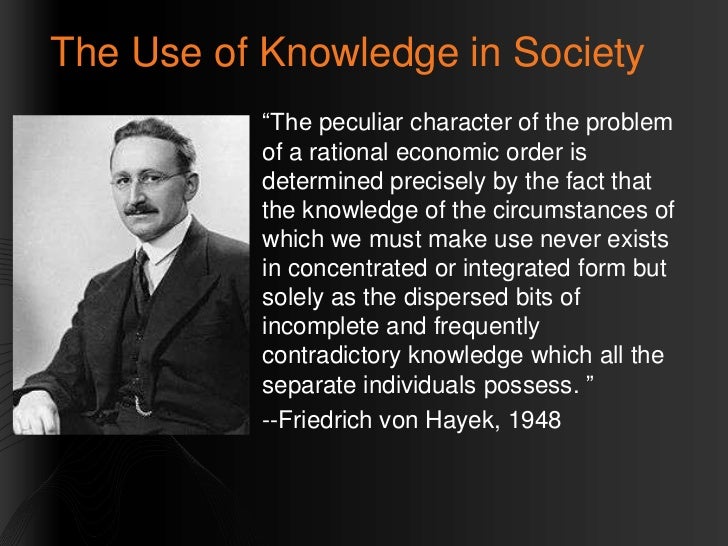

That’s really nothing to be embarrassed about: if one wants to live a decent life — or just live, really –one has to accept much more as known by science than one can comprehend to any meaningful degree.

What is embarrassing, though, is for those who don’t understand something to claim that their “belief” in it demonstrates that they have a greater comprehension of science than someone who says he or she “doesn’t” believe it.

I agree with Kahan. Accepting at least some of the conclusions of science–and authorities in general–beyond our personal ability to verify is essentially prerequisite to functioning in this world. But let’s not pretend that means we understand science merely because we accept it. And let’s definitely not make science into another piece in the age old war of “who is the better, smarter, and more handsome group.” If you’re worried about the state of science, I can promise you that even a large number of yahoos believing silly things won’t destroy science, but politicizing science most certainly will.

Drawing on a large sample from Sweden, a new

Drawing on a large sample from Sweden, a new

A

A