When it comes to telephone calls… nobody is listening to your telephone calls. That’s not what this program is about. As was indicated, what the intelligence community is doing is looking at phone numbers, and durations of calls. They are not looking at people’s names, and they’re not looking at content. But by sifting through this so-called metadata, they may identify potential leads with respect to folks who might engage in terrorism. – President Barack Obama

It’s just metadata, folks. Not names or content. No big deal, right? On the other hand:

But metadata alone can provide an extremely detailed picture of a person’s most intimate associations and interests, and it’s actually much easier as a technological matter to search huge amounts of metadata than to listen to millions of phone calls. As NSA General Counsel Stewart Baker has said, “metadata absolutely tells you everything about somebody’s life. If you have enough metadata, you don’t really need content.” When I quoted Baker at a recent debate at Johns Hopkins University, my opponent, General Michael Hayden, former director of the NSA and the CIA, called Baker’s comment “absolutely correct,” and raised him one, asserting, “We kill people based on metadata.”

So, yeah. Guess President Obama’s “it’s only metadata” comfort isn’t so comforting after all. The rest of the article from whence that quote came is a description of the USA Freedom Act: what’s good, and where it doesn’t go far enough. I’m not sure I really follow all of the arguments. I do agree with the author, David Cole, that we need to balance safety against civil liberties, and that merely saying “people will die if we don’t record everyone’s metadata” is not, all by itself, enough to justify recording everyone’s metadata. But they key word there is balance.

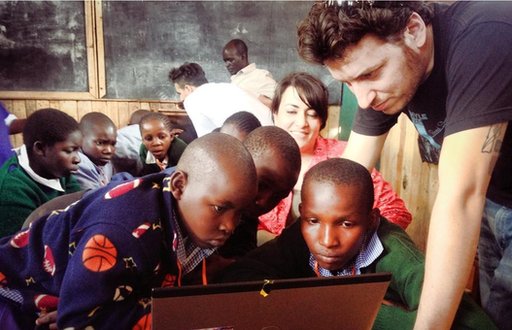

I’m not sure that effectively rolling the clock back to the 20th century and pretending that Big Data isn’t a thing is really the way forward, either. There is immense power in the aggregation and analysis of vast quantities of data, and this isn’t just about terrorism. It’s about tracking disease outbreaks, learning more about the economy, making traffic safer and more efficient, and applications we haven’t even thought of. The potential to make the world a better place or a worse place based on data analysis is too big to ignore and, quite frankly, too enticing to resist.

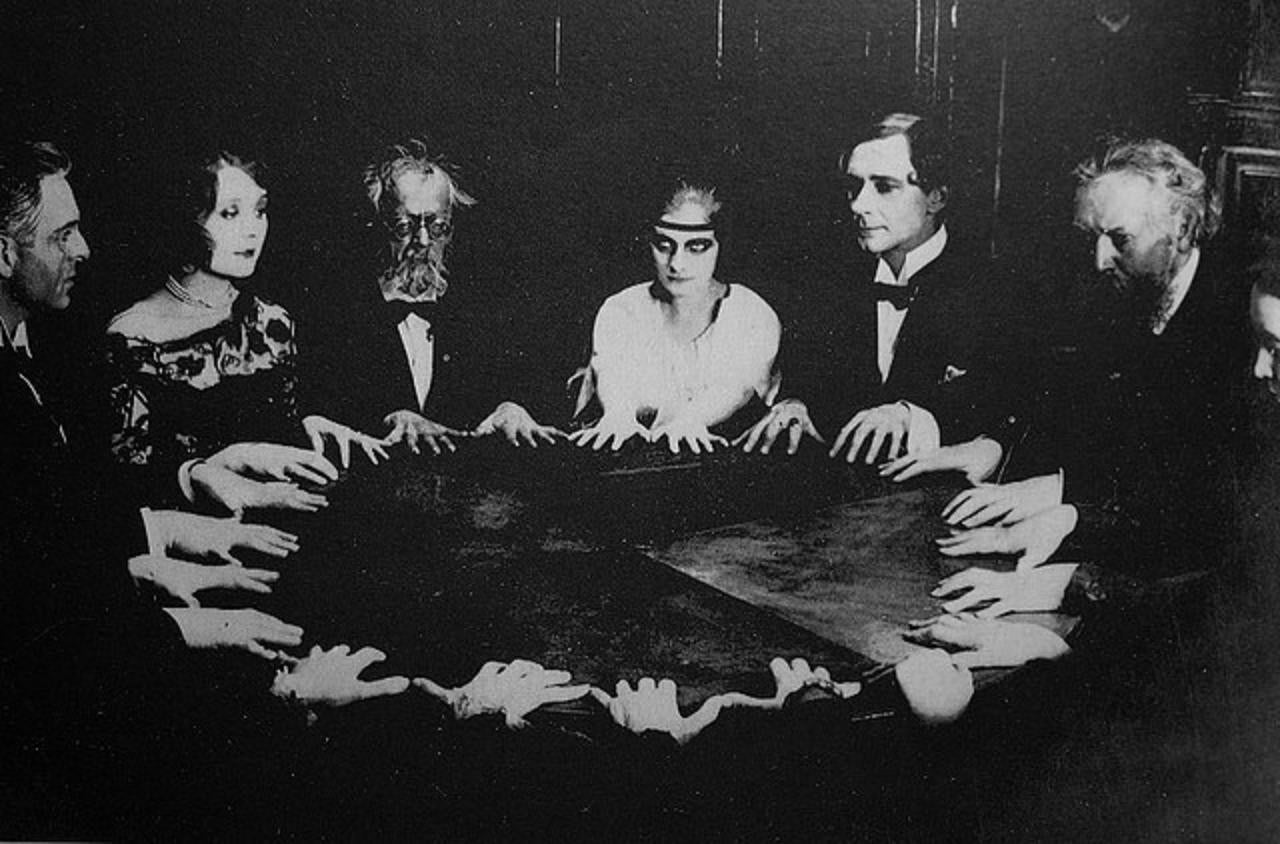

Just like the European Union and their sadly laughable “right to be forgotten,”[ref]I see no practical way for Google or anyone else to actually enforce this law[/ref] laws based on trying to pretend that the data isn’t there or force people to not use it are likely to only succeed in making sure that the folks who harness and use the data that is already there do so in the shadows. And that’s creepy, whether it’s the NSA deciding who to kill based on metadata or Target sending pregnancy-related advertisements to teenager girls. Rather than prohibition, what I think we need is more clarity about how to collect and use the data in a way that is transparent and commensurate with a new understanding of what privacy really means in the 21st century.

The one thing we can be sure of? It won’t mean what people are used to it meaning. That’s OK. After all, in Scandinavian countries like Sweden, Finland, and Norway, every citizens individual tax returns are published publicly every year. Very different from what we’re used to, sure, but no one really cares over there. I’m not saying we should move to that model. I’m just saying that what certain folks have in mind when they think of “privacy” as a civil liberty is actually a lot less like an inalienable right and a lot more like an individual cultural preference. But if we can’t have a conversation about radically new understandings of privacy to go along with our radically new capacity to aggregate and analyze data, then we can’t take a hand in choosing our own fate.